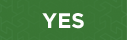

Have a seat and drive a car around a topologically-inspired track! You can see what the car’s dash cam sees on your display screen. Does what you see as it makes a full lap around its track surprise you? Why do you think there is only one car on one of the tracks but two cars on the other?

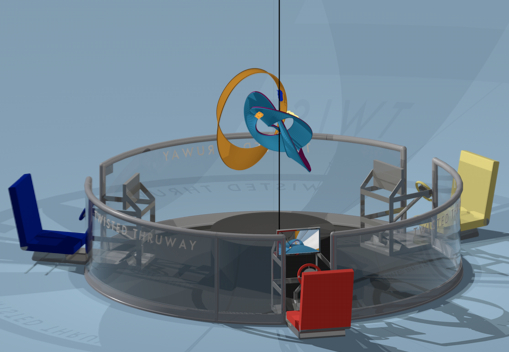

Suppose you take a long paper strip and tape one end to the other. What would you get? If asked to do this, most of us would probably make something that looks like the label for a tuna fish can. This shape is called a cylinder.

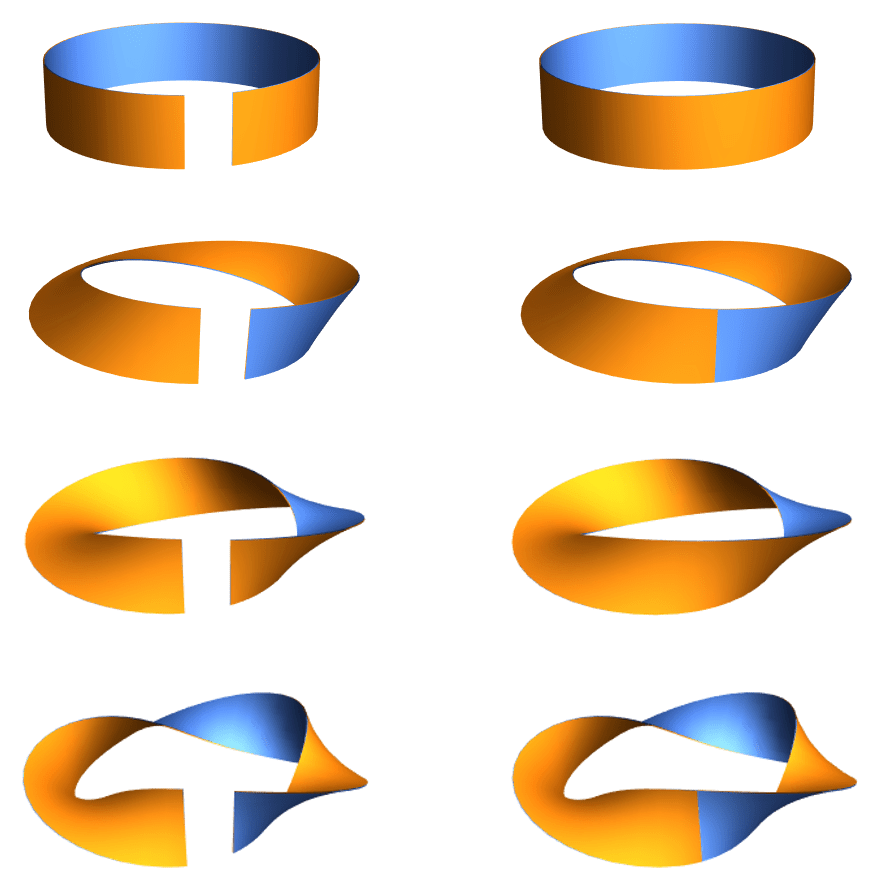

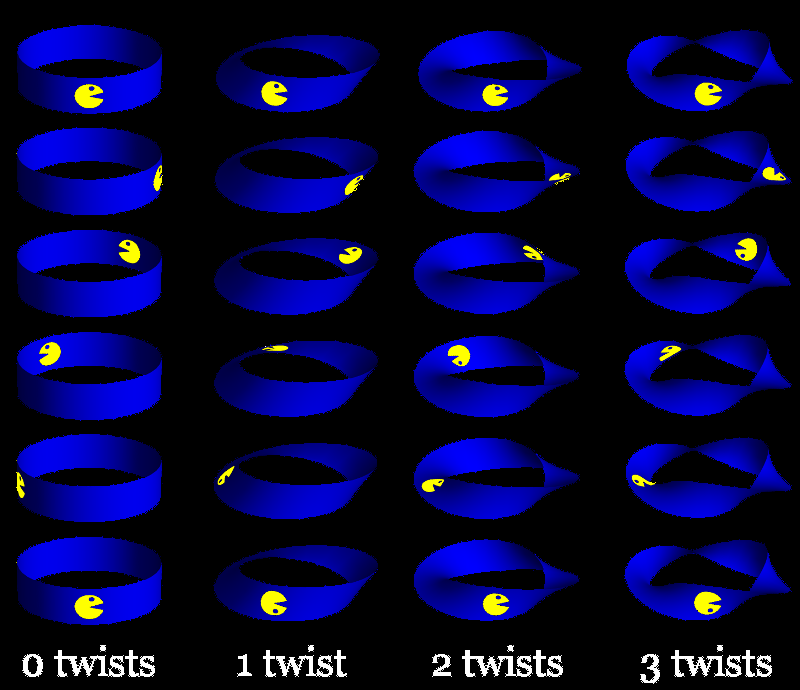

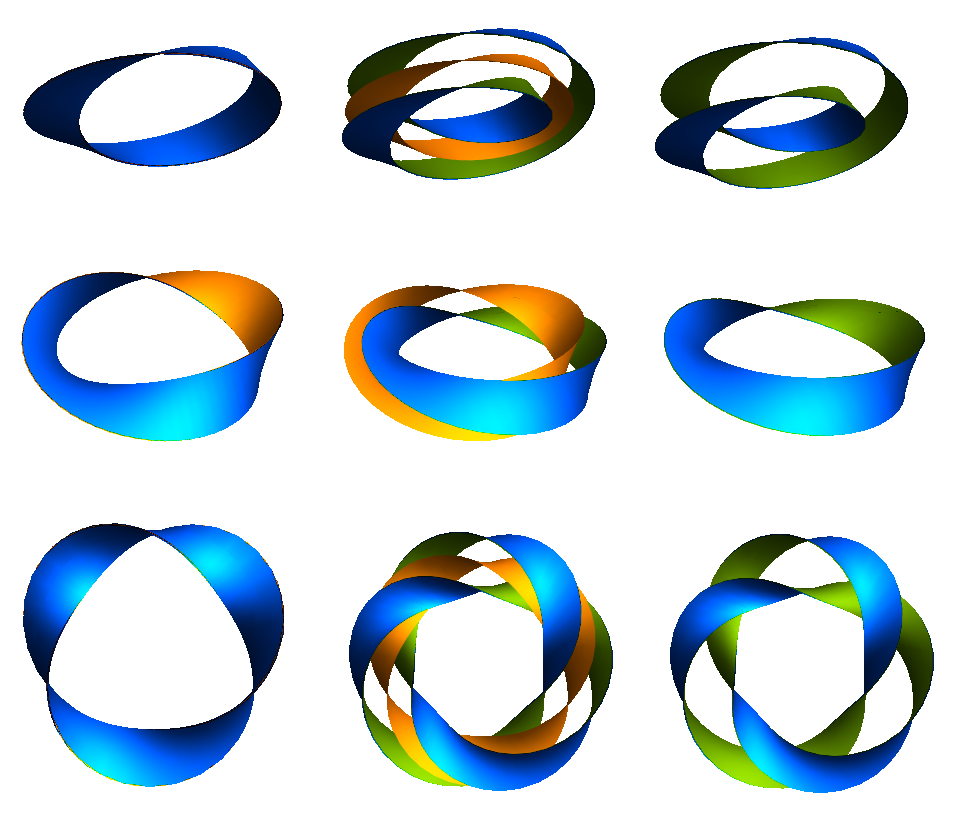

On the other hand, we could get a little more creative and twist the strip before taping its ends. If we were to twist it once, we would introduce half a turn into the strip and get what mathematicians call a Möbius strip. We could twist once, twice, thrice, or more! We could twist clockwise or counterclockwise. What sorts of shapes would we end up with?

One way to try to tell the difference between the different shapes we can make is by first coloring the two faces of our strip orange and blue. What do we notice when we make our twisted shapes using this colored strip? Sometimes orange matches up with orange, but other times orange matches up with blue. Can you see the pattern?

As we twist the strip, the end we’re twisting switches from orange to blue. This means that after an even number of twists, we’ll see orange line up with orange, while after an odd number of twists, orange will line up with blue. An even number of twists results in a surface where there is still an orange side and a blue side, so we can still talk about sidedness — like the front and back of a strip or the inside and outside of a cylinder. An odd number of twists, on the other hand, creates a surface that has only one side, since we can see that blue and orange are now on the same side!

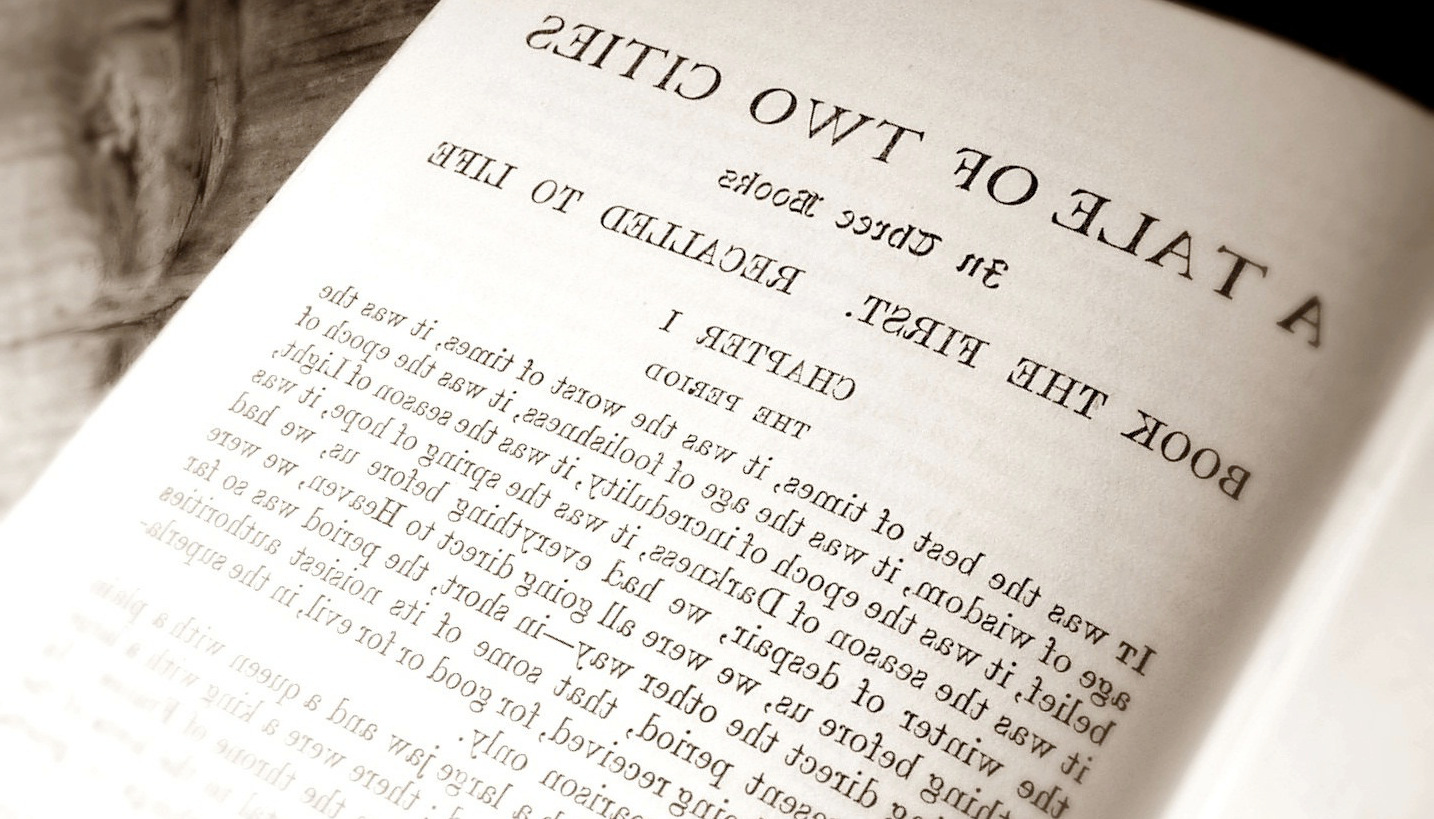

Imagine leaving your house to go for a walk, but things seem a little off when you return. The doorknob is on the left side of the door instead of the right. Once inside, you pick up a book and notice that the title is backwards. Leafing frantically through the pages, all of the words read from right to left and you have to hold the book up to a mirror to read it! Feeling ill, you go to the doctor for a check-up, and when using her stethoscope to listen for your heartbeat she can’t seem to find it — because your heart is now on what’s she’s calling the “right” side of your body. She holds up what appears to be her left hand and says “this is my right hand,” trying to explain. This would be a pretty hard world to navigate. You think you’ve got left and right down, but every time you leave your house, you might return to find they’ve switched places. People might say, “take the first left,” but actually mean, “take the first right.” How disorienting! What could be going on here?

When you think of a shape in the plane, you don’t worry about whether it’s on top of or underneath the plane — it’s simply in the plane. When mathematicians study the Möbius strip, they usually don’t think in terms of sides, either, but rather in terms of orientation, since this doesn’t depend on the space around it.

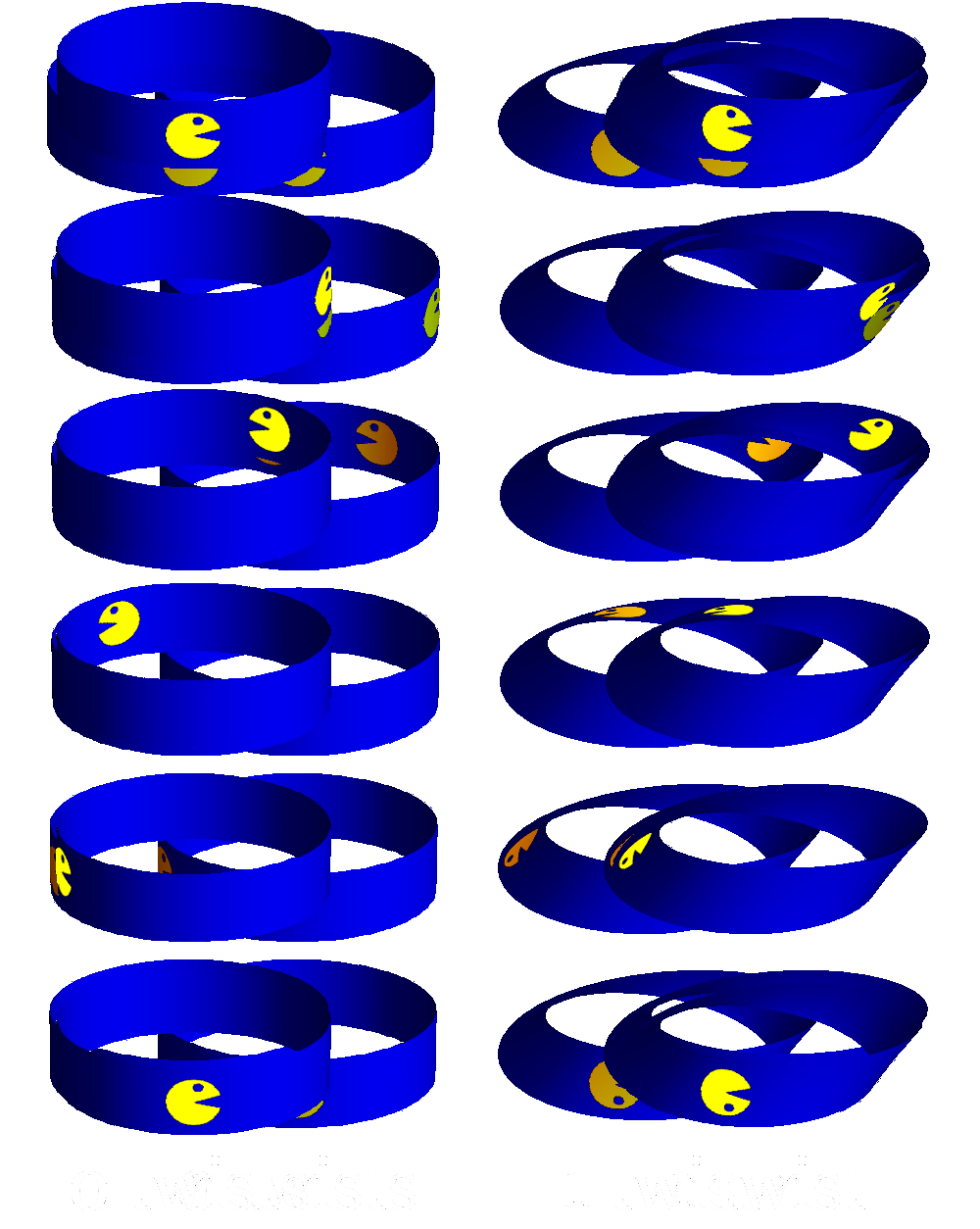

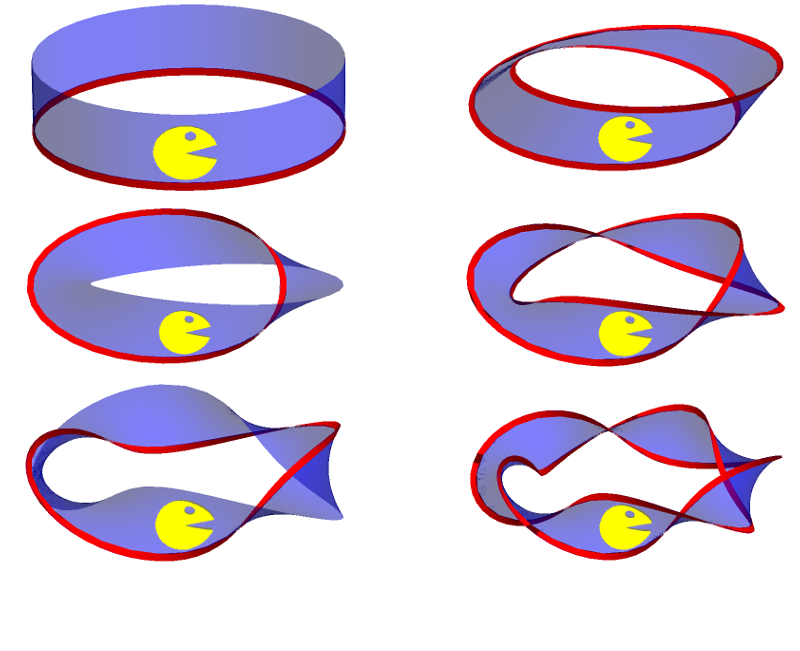

If you’ve ever played Pac-Man, you might recall that he can roll off one side of the screen and take a hidden passageway to the other side. To the right are two possible paths Pac Man might take to end up back where he started. In the cylindrical path, we see him start in front, work his way around the back, and then reemerge front and center. A similar thing happens on the Möbius strip path, but something’s a little off. If you look closely, his eye is now on the bottom of his head! No matter how he rotates, he will continue to be the mirror image of the Pac-Man who started this journey. If he could flip like a coin, he’d be back to his old self, but he can’t flip out of the 2D strip. He can always take another lap around the Möbius strip to set himself straight, though!

A Möbius strip is an example of a nonorientable surface, since we’re bound to confuse clockwise with counterclockwise after enough laps. (In fact, any 2D nonorientable surface contains a Möbius strip, since these confusing laps are the heart of nonorientability.)

You might have heard of the Klein bottle, often described as “a bottle whose inside is its outside,” a fuzzy description that a mathematician would read as “the Klein bottle is nonorientable.” See if you can pick out a Möbius strip in the picture to the right. (Note: The Klein bottle, despite being 2D, can’t be embedded in 3D without self-intersection!)

While the universe has so far behaved like an orientable 3D manifold in the ways we interact with it, it is fun to think about Möbius strip-like paths we could take that switch our notions of left- and right-handedness. What would such a path look like? Even though the Möbius strip is a 2D surface, we needed a third dimension to “twist” it. Analogously, you might start with a hallway with a door on each end, rotate one end through a fourth spatial dimension to “twist” it, and then connect the doors together. (Walking through an even number of doors would leave your heart in the right place!)

If we explore how Pac-Man navigates strips of varying twists, another pattern emerges. Just as an odd number of twists gave a one-sided band while an even number of twists gave a two-sided band, even-twisted bands are orientable while odd-twisted bands are nonorientable. While we can see a difference between an untwisted band and a twice-twisted band, what does Pac-Man see? Since he doesn’t have access to our 3D glasses, perhaps he can’t tell the difference.

He could painting an edge red. If he did this on an even-twisted band, he’d see that the other edge is still blue by the time he’s done. On an odd-twisted band, he’d find there was only one edge! He would continue to learn interesting facts, but every test his 2D brain can conceive wouldn’t tell no twists from two twists. Such topologically equivalent spaces are homeomorphic. As 2D manifolds, the untwisted and twice-twisted bands are homeomorphic, so we can rightfully call them both cylinders! Similarly, the thrice-twisted band is a Möbius strip.

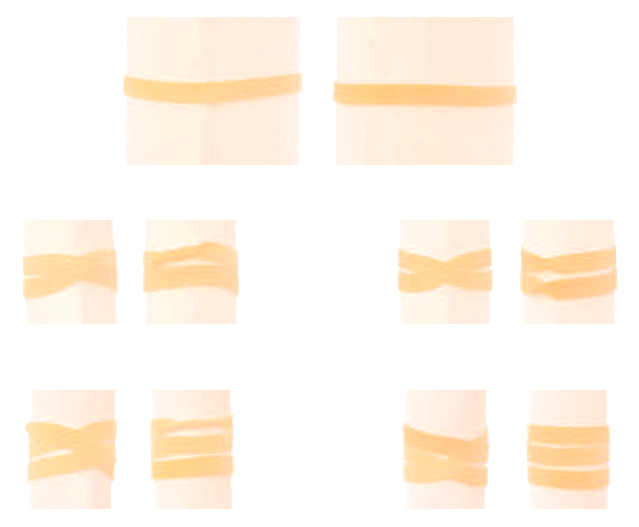

While there’s no difference between zero and two twists in a 2D world, there is in 3D. Have you ever tried wrapping a rubber band around a rolled up paper? It’s easy to imagine what it would look like if you were to wrap once around. However, if you wrap the rubber band around a second time, you’ll find that it no longer lies flat. It certainly has to cross over itself in order to double-wrap, but what’s with the twist in the band? No matter how you try to straighten out the twist, it just moves elsewhere or spreads out. If you try wrapping it around a third time, about half the time it just gets more impossibly twisted. The other half the time, with some gentle coaxing, it lies flat again!

Suppose you took a ridiculously long belt and wrapped it around your waist twice before buckling it, making sure to always keep the inside towards your waist as you wrap to avoid twisting. If you were to shimmy out of it, you’d notice that you’d inadvertently introduced some twists — two twists, to be precise! If we made rubber bands with two twists prebuilt in, then we’d be able to double-wrap our rubber bands so that they lie flat like the belt. (On the other hand, if we wanted to wrap once or thrice, we’d be out of luck!)

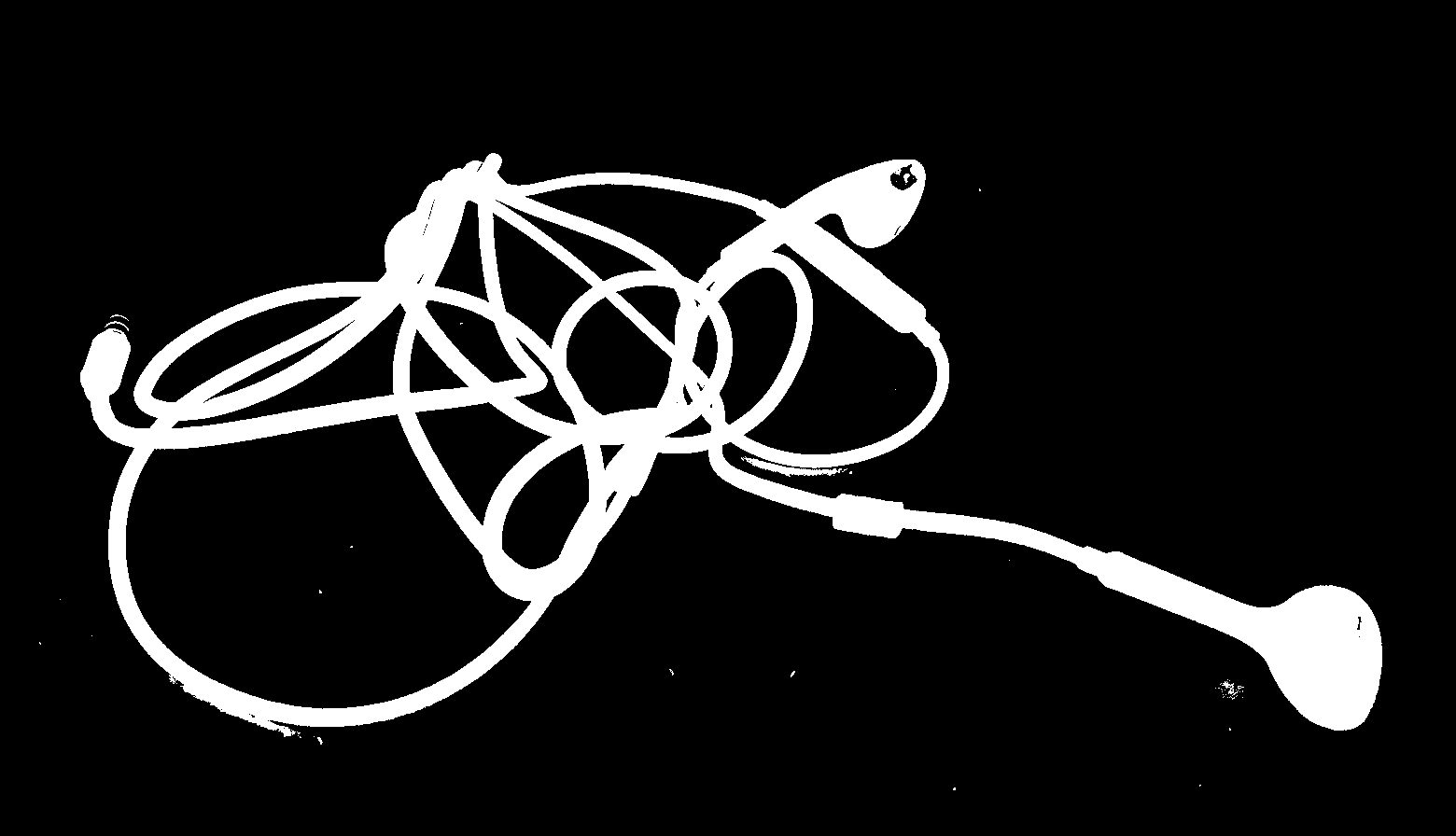

Sometimes the way that something interacts with the space around it is the most interesting thing about it! Every earbud owner knows detangling a wire can be a challenging task. If you build a wall around your garden, it will keep out rabbits and other ground dwellers, but birds can easily fly through the third dimension and enter your garden. Similarly, if we lived in four dimensions, we wouldn’t know what it would mean for a wire to be tangled. There is something very peculiar about the way a 1D wire obstructs itself in a 3D space!

Because your earbuds always have a free end, you know that you’ll be able to untangle them eventually. Suppose, on the other hand, that you stumbled upon a tangled extension cord that had been plugged into itself. Do you think you could untangle it without first unplugging it? Sometimes you can and other times you can’t! The study of these tangles of cords with their free ends fused together is called knot theory.

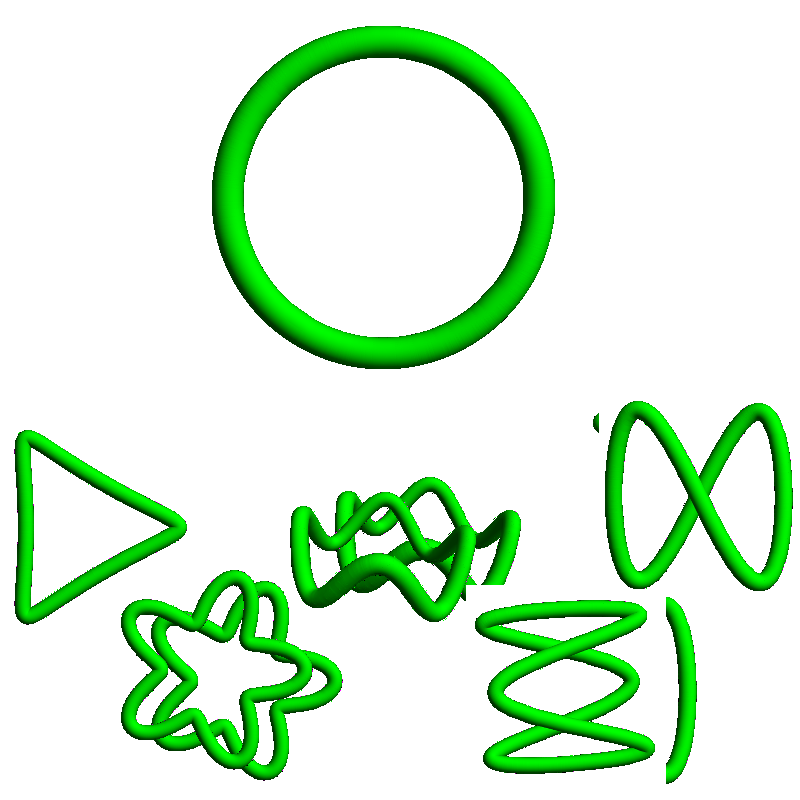

The simplest structure you can make after fusing the ends of a rope together is a big open circle. While technically every knot is an embedding of a circle in 3D space, the one pictured to the right is interesting — or perhaps uninteresting? — because it has no places where it crosses over itself, so it is completely untangled. Mathematicians call this, and the various different shapes you can maneuver it into, the unknot.

Given a random knot, it can be quite difficult to tell whether it is the unknot in disguise! You can try to untangle it into a nice open loop, and if you’re able to do it, then you’re obviously holding the unknot. If you can’t though, how long do you have to play with it before you can give up and declare that it’s not the unknot? Ten minutes? Ten years? If you played with a knot for a few hours and then handed it to a friend, declaring “this definitely won’t come unknotted,” and then watched her effortlessly unknot it, you’d probably feel a little silly! Mathematicians need to be absolutely sure a knot cannot be unknotted before telling their friends, which can be a very tricky business.

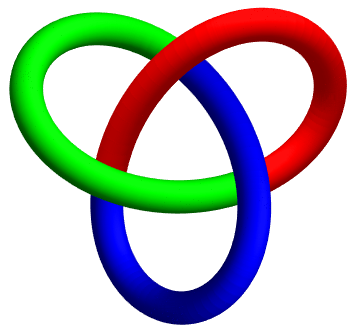

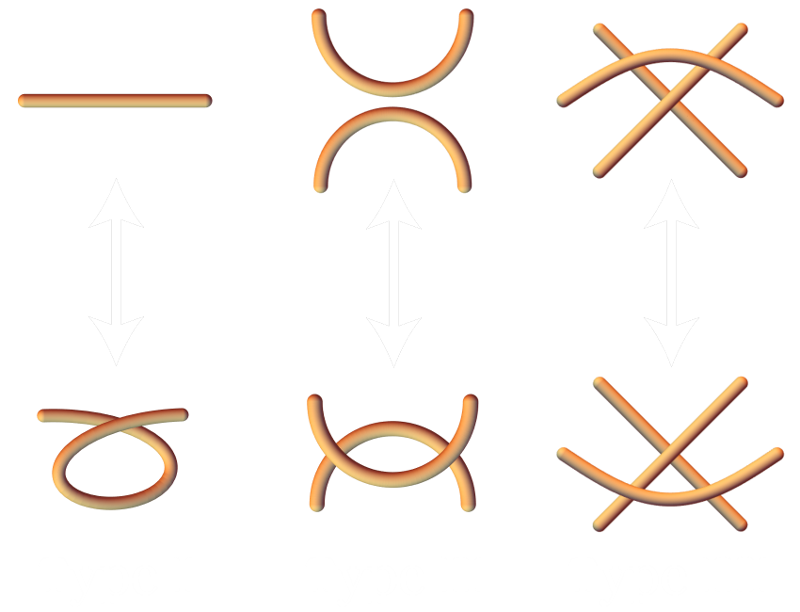

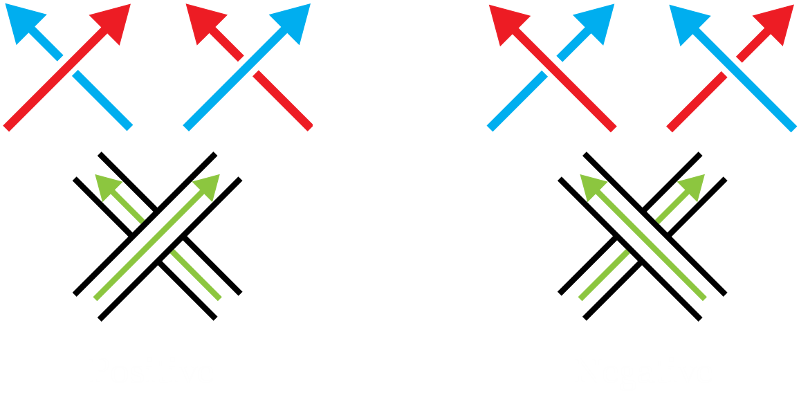

The trefoil knot is the simplest knot that’s not the unknot. The trefoil to the right has been colored in a strange but useful way. Consider maneuvers we make when trying to untangle a knot. If we lay a knot on a table as we work to untangle, we might note that the things we’re doing are essentially combinations of three types of moves: adding or removing twists from a strand, overlapping or un-overlapping two strands, and moving a strand from one side of a crossing to another. These three maneuvers are called Reidemeister moves and if you can maneuver one knot into another, you can do it using only these three moves.

A tricoloring of a knot is a way of coloring the arcs of a knot so that at every crossing, either all three arcs involved are the same color or all of them are distinct colors. If a knot is tricolored before a Reidemeister move, then there’s a way to fix the colors after the move so that it’s still tricolored. Tricolorability is a knot invariant, since you can either tricolor a given knot in all of the ways you can position it or none of them. Our picture shows the trefoil knot is tricolorable while the unknot is not, so this is one way to tell them apart!

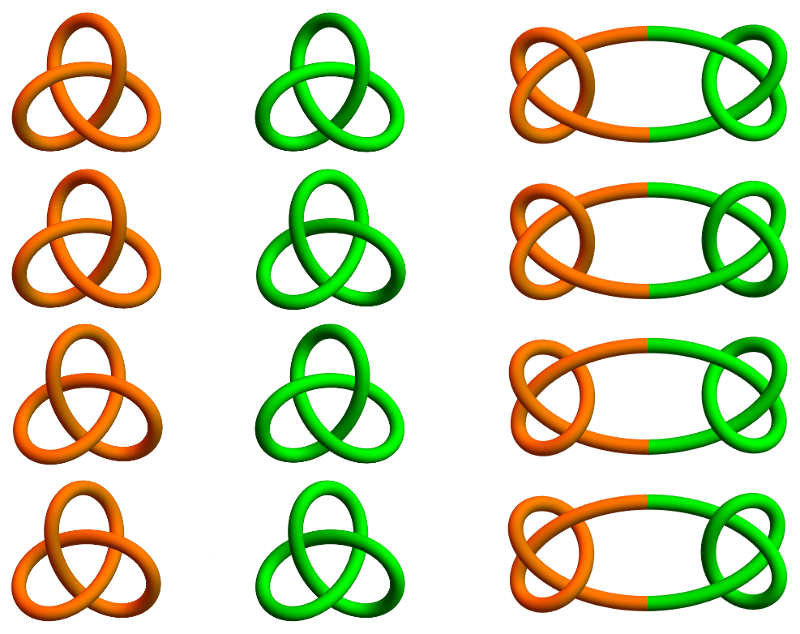

So far we’ve seen the unknot and trefoil. What are some other knots? One easy way to make a new knot is to tie several knots into the same loop, forming what is called a composite knot. Even with two trefoils this is already a little complicated. This is because the trefoil is chiral — it cannot be maneuvered to look like its mirror image. One way to think about tying two knots into the same loop is to snip each and then fuse their ends together, forming the connected sum. (Making sure you always get the same thing when you start with two knots requires some care, so we’re sweeping some stuff under the rug.)

Depending on the handedness you choose for each trefoil in the connected sum, there are four possible ways to connect them. Ignoring color, notice that the top and bottom knots are mirror images as are the middle two. The middle two can actually be rotated into one another while the outside two are chiral. The middle two are square knots while the top and bottom two are left- and right-handed granny knots.

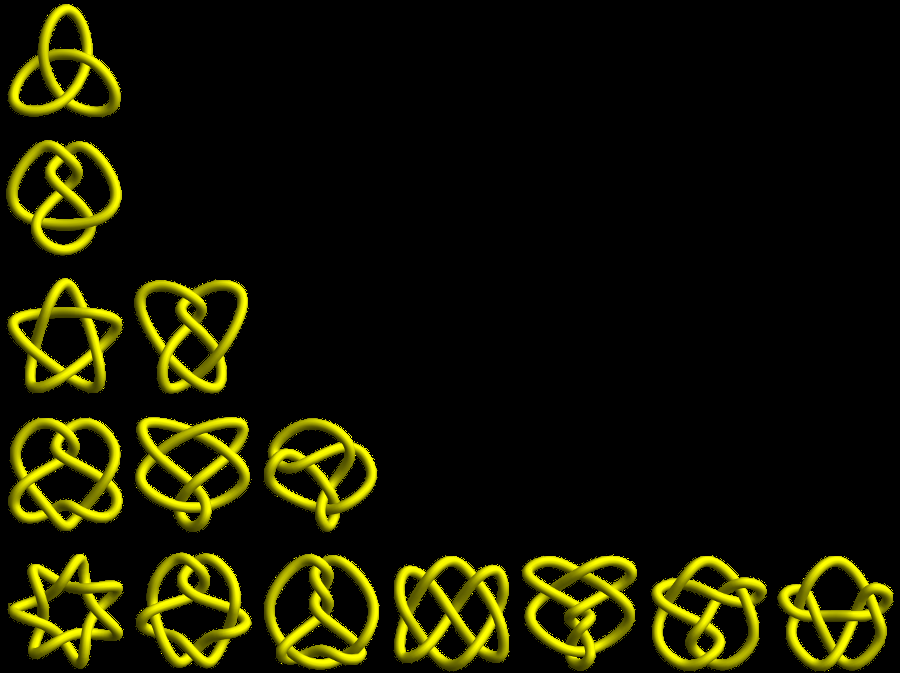

Just as any integer can be factored into a product prime numbers, similarly any knot can be factored into a connected sum of prime knots. To the right is a collection of some prime knots arranged by crossing number, which is the least number of times that a knot can cross over itself when placed on a table. An unknot can cross over itself, but because we can maneuver it so it doesn’t, its crossing number is 0. The trefoil has crossing number 3, which is the lowest crossing number of any nontrivial knot. (If you see a knot with 1 or 2 crossings, it must be the unknot in disguise!)

There is only one knot with crossing number 3, if we don’t count the chiral trefoils separately. The knot with 4 crossings is the figure 8 knot. The two knots with crossing number 5 are the pentafoil and the three-twist knot. It turns out that the number of prime knots with a given crossing number grows exponentially. Claus Ernst and Dewitt Sumners proved that the number of prime knots with crossing number n > 3 is at least .

Mathematicians suspect that you should be able to add the crossing numbers of two knots to get the crossing number of their connected sum, but nobody knows for sure!

If we make our knots out of bands intead of rope, then there is also the possibility of putting twists into the band. The knotted band to the right is equivalent to the trefoil track. If you study the track, you can probably convince yourself that it has two sides and two edges. This is why two cars can race on it without ever crashing — each stays on its own side of the track! If you look closely, one side of the track is purely convex while the other is purely concave. You could arrange the track so that one edge is always up and the other down. This means that if you were to stand in the center of this track, you could think about it as being like a large belt around your waist that has wrapped around twice. Any such belt must cross itself at least once as it wraps around, but this one crosses itself three times and forms a trefoil knot. While the track might appear untwisted, we know that if a belt lies flat around our waist after wrapping twice around, it must actually have two twists in it!

Suppose we painted the entirety of an orange Möbius strip blue. If we started carefully peeling that paint off, we’d have a two-sided band — the blue outer side and the inner side that had been contact with the Möbius strip, shown in green. When a car races around the Möbius strip track, we can think of it as racing around the blue side of this two-sided track. This two-sided track has four twists in it: one for each twist in the Möbius strip and an extra two twists because of the way this track winds around the center twice.

If we try this with a two-sided band, such as a band with two twists, painting only one side and peeling it off gives us another copy of the original band. If we paint each side a different color, we might find that the two paint bands are linked together once we peel them off!

If we try this with a thrice-twisted Möbius strip, we’ll end up seeing that the new surface we create is tied into a trefoil knot. It’s not the same trefoil track as the one in this exhibit, though, since this one has eight twists in it. Painting strips with larger numbers of odd twists will give us more elaborate knots when we peel.

An interesting formula for an even-twisted band (sometimes called a ribbon) is the Cǎlugǎreǎnu-White-Fuller formula:

,

which relates the linking number, writhe, and twist of the ribbon.

To compute these numbers, color one edge of the ribbon red, the other edge blue, and and the center line green, and give them all the same orientation. is the number of red/blue positive crossings minus negative crossings, divided by 2. is the number of green positive crossings minus negative crossings. (These two must be computed from the same perspective!) is the number of full twists in the band – i.e., half the number of what we’ve called twists. Counterclockwise twists are positive and clockwise twists are negative.

In 2018, topologist Lisa Piccirillo (b. 1991), then a graduate student, stunned her colleagues with her resolution of a decades-old problem about whether a knot named after the late great mathematician John Conway satisfied a funny property called being “slice.” Piccirillo is now a researcher at MIT, and one imagines, would enjoy driving a little car along Conway’s knot much the way visitors to MoMath drive along a trefoil knot on the Twisted Thruway exhibit. Photo courtesy of MIT News.

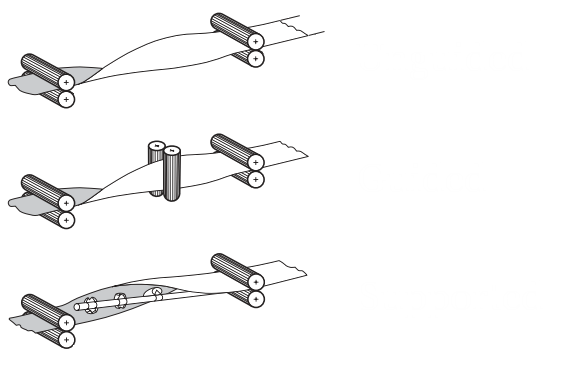

Conveyor belts are ribbons of some material formed into a loop. At a grocery store check-out counter, you only see part of this belt at a time — the half that isn’t touching your groceries is hidden away in the lower deck of the machine. While this likely doesn’t happen at the grocery store, many industrial conveyor belts use a turnover system to put a half-twist into the portion of the belt in the lower deck, turning it into a Möbius strip. A cylindrical belt has two sides, only one of which experiences wear from the loads placed on it. A Möbius band belt experiences even wear along the entirety of its one side

To the right we see a guided turnover system in the lower deck of an industrial conveyor.