With fixed start and end points, what shape would you make this track so that the cart reaches the end in the least amount of time?

The shortest path is a straight line, but the only thing that makes the cart move is gravity. Since gravity speeds the cart up most when the path is steepest, maybe it is faster to let the cart go down steeply at the beginning, before shooting across to the end. But how much should it drop, and where along the path?

Try different shapes for the curve. Which shape gives you the shortest time?

What gets the cart rolling? It doesn’t have a motor so instead it relies on gravity to make it move. Gravity is something that physicists call a force. That means that when a light object – like a cart in Tracks of Galileo – is given the opportunity to get closer to a very, very massive object – in this situation, the Earth – it will. And it will move towards it at faster and faster speeds the farther it falls, meaning that it accelerates. The farther the cart falls, the faster it will roll.

So, how does this affect the shape of the fastest track? It’s a basic mathematical fact that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. But for the shortest distance to take the shortest time assumes that the object travelling along the path is moving at the same speed the whole time. Here, the ball rolls faster and faster the farther it rolls down.

A curve that gets the ball rolling fast at the beginning is a good candidate for a fast overall trip. What shape track would get the ball rolling very fast in a very short amount of time?

To get the cart rolling fast, the best track will be vertical, or very close to vertical, at the beginning. Once it picks up speed, the track will start to flatten out. The cart still speeds up on a not-so-steep track, though not as much. As it gets closer to the finish, the track can flatten out a lot – the cart is moving very, very quickly at this point, so the track should make the most use of this speed to get it to the end.

Try to make a track that does this: starts out vertical, flattens out gradually as the ball picks up speed, and then makes the most of the ball’s speed by hurtling it directly at the finish.

Mathematicians studied the problem of the fastest track for many, many years before finding the perfect solution. They thought about questions much like you have: Is the straight line really the fastest? How do you make the ball speed up? The curve that they found always makes the fastest track, no matter where the starting and ending points are (as long as the starting point is above the ending point), looks a lot like the one described above. It’s called the cycloid.

Notice how a cycloid starts out very steep, then flattens out, and then turns back upwards again. Now, you may be thinking: What about that upwards bit? Wouldn’t including a portion in the track that slopes upwards slow down the ball? Interestingly, the cycloid is always the best shape for the track – even if it has to slope upwards at the end to make it cycloid-shaped. To learn more about why the cycloid is the best shape for the track, and to learn more interesting things about cycloids, see the Intermediate More Math section.

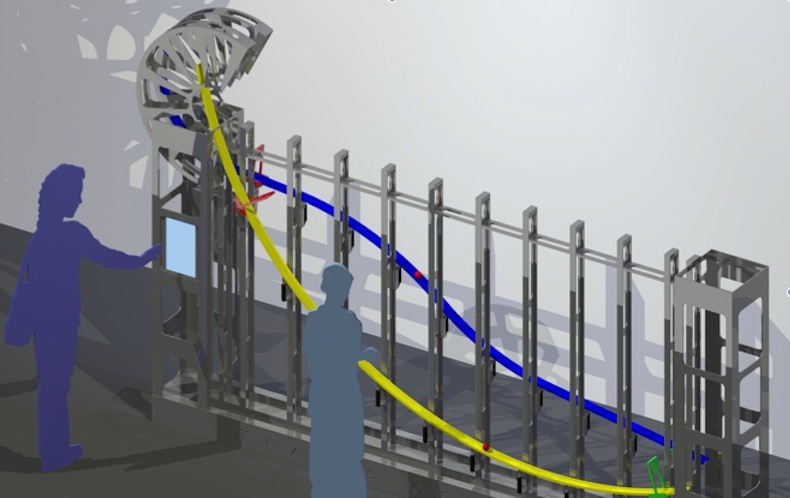

The top blue curve – the straight line – may be the shortest distance between the start and the finish, but the red curve – the upside down cycloid – is actually the fastest track. Which of the two blue curves do you think makes the faster track?

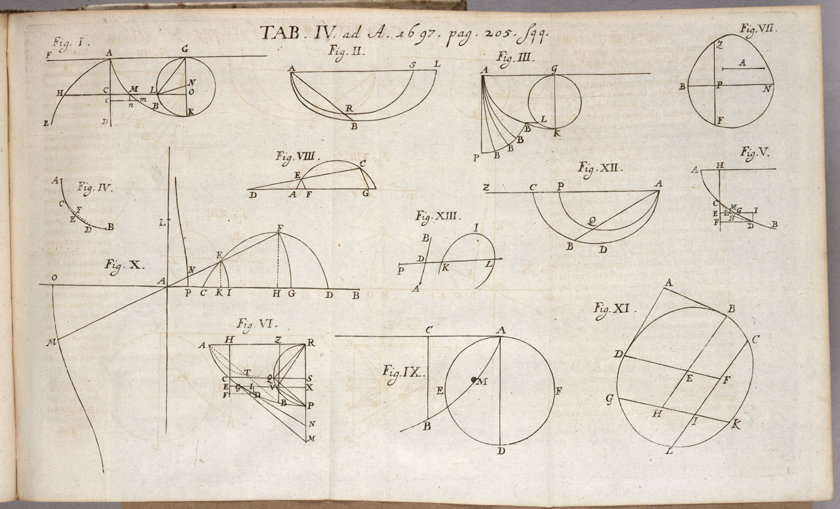

This is a page from the article written by Johann Bernoulli about his and others’ solutions to the brachistochrone problem. The first three figures are Bernoulli’s solution. The other images are the solutions Bernoulli received from his brother, Jacob Bernoulli, Guillaume de L’Hôpital, René Descartes, and Isaac Newton.

This is a model of the best possible track – or brachistochrone – made at the end of the eighteenth century by Francesco Spighi. It is on display at the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy.

This animation shows how a point on the rim of a rolling circle draws the cycloid curve. The cycloid curve, flipped upside-down, is the best track.

Google, Inc. provided support that made Tracks of Galileo possible.

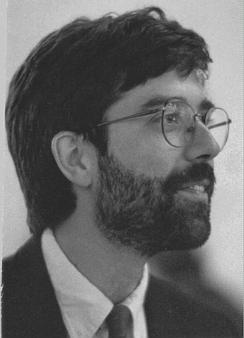

Robert Kohn is a professor of mathematics at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University. Professor Kohn’s research has helped advance mathematical disciplines related to Tracks of Galileo.

Gary Lawlor is a professor of mathematics at Brigham Young University. Professor Lawlor’s research has contributed to mathematical fields related to Tracks of Galileo.

American mathematician Vivienne Malone-Mayes (1932 – 1995) would have had no trouble using her work in functional analysis, non-linear operators, and differential equations to find the track giving the fastest path from the top to the bottom of this configurable track. Born in Waco, Texas in the height of segregation, she overcame adversity to become a Professor of Mathematics at Baylor University.

Frank Morgan is a professor of mathematics at Williams College. Along with teaching college students and writing books about math for all kinds of readers, Frank studies bubbles. What fun! To do this, Frank uses calculus of variations – the mathematics involved in this exhibit.

One use of the mathematics behind this exhibit is making go-kart tracks. The solution to our problem of building the fastest track has also helped mathematicians, physicists, and engineers solve many other very useful problems.

Any time an engineer wants to know, “What is the best shape to design the arch of this bridge I’m building?” or, “What route should my airplane take so that I get to my destination taking the least amount of time and fuel?” that person will use the ideas that mathematicians came up with when solving this problem. Those ideas are part of a kind of math called the calculus of variations – math that studies changing the shape of something to make it the best for a particular need.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) spent much of his life studying falling objects. The most famous story about Galileo is about him dropping objects off of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. As the story goes, he discovered that heavy and light objects will hit the ground at the same time if dropped at the same time. This story might not be true, but it is true that Galileo experimented with tracks for rolling objects like the ones in this exhibit. He was inspired to study tracks for rolling objects by his experiments with a pendulum – a heavy object tied to the end of a string that swings back and forth.

In a book published in 1638, called Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two New Sciences, Galileo showed that an arc of a circle was a faster path for an object rolling between two points than a straight line. Remarkably, Galileo published this book while he was under house arrest for believing that the Earth rotates around the Sun.

The math that existed during Galileo’s life was not advanced enough for him to test other shapes, or for him to guess the shape that makes the fastest track. But Galileo did bring up a problem that would interest mathematicians and physicists for many years – and lead to the creation of a new type of mathematics!

Try this next time you’re drinking something out of a glass with a straw: Look straight down into the glass. What do you see? The straw looks bent – even though it’s straight! Why does this happen?

Physicists and mathematicians in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were very interested in this question. The reason why the straw looks bent is because light travels faster in air than it does in the water, so it bends. This is called refraction. The Dutch physicist Willebrord Snellius (1580 – 1626) described exactly how the image bends in a law called Snell’s Law. Later, the mathematicians Rene Descartes and Pierre de Fermat both proved it mathematically.

What does the bent-looking straw sticking out of water have to do with this ball-and-track problem? Well, the mathematicians who eventually found the shape of the best track realized that the situations are almost the same. Light travels more slowly in water than in air, so it speeds up suddenly as it passes from water to air. Light is traveling on the least-time path.

The way that scientists and mathematicians worked on the problem of refraction also shows a lot about how they thought about the world – which is important to the ball-and-track problem. Snellius, Descartes, and Fermat, and many of the scientists and mathematicians that came after them, thought that everything in nature follows very strict rules. They thought that those rules could be described by math and tried to prove things that happen in nature using mathematical rules.

Galileo’s question really got mathematicians thinking about the paths of falling objects. Mathematician, astronomer, and physicist Christiaan Huygens (1629 – 1695) took up the study of objects rolling along paths in the 1650s. He is best known for studying the rings and moons of Saturn and for arguing that light travels in waves. Much like Galileo, Huygens got to this question by studying pendulums. He was trying to build a pendulum clock, a clock that keeps track of time with a pendulum that swings back and forth inside of it. He wanted the time it took for his pendulum to swing to have nothing to do with the height from which the pendulum started swinging.

Huygens wondered if he could build a path so that if he let one object go from one place along the path and a second object from a different place along the path, both objects would reach the end of the path at the same time. He called this possible curve an isochrone – made up of the Greek words “iso,” which means same, and “chronos,” which means time.

It turns out that both questions have the same answer, an upside-down cycloid. A cycloid is the curve traced out by a reflective disk on a rolling bicycle wheel, when the wheel has that disk attached right on the edge. For each radius of the wheel there is a different cycloid, but these are different only in scale. In these curve problems, you pick the upside-down cycloid that has a vertical slope at the start point and then choose the scale of the cycloid so that it passes through the finish point.

Christiaan Huygens found the cycloid earlier to be the answer for his isochrone, and mathematician Johann Bernoulli (1667–1748) proved it to be the answer for his brachistochrone (made up of the Greek words “brachistos,” which means shortest, and “chronos,” which means time). Then Bernoulli challenged several other famous mathematicians to answer his question too, keeping his solution secret. They all found the cycloid as well.

Bernoulli’s solution introduced a new type of math problem, in which mathematicians compared curves to see which was the best at doing a particular thing. This type of problem is studied in what is now called calculus of variations.

Nahin, Paul J. When Least is Best: How Mathematicians Discovered Many Clever Ways to Make Things as Small (or as Large) as Possible. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004.

This book discusses the history of the development of calculus by narrating stories of mathematicians solving maxima and minima problems. There are several chapters on the Brachistochrone problem and the development of calculus of variations.

Lemons, Don S. Perfect Form: Variational Principles, Methods, and Applications in Elementary Physics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997.

This book explains the calculus of variations from a physics perspective. It introduces the ideas of calculus of variations through the Brachistochrone problem.

Tikhomirov, V. M. Stories about Maxima and Minima. American Mathematical Society and the Mathematical Association of America, 1986.

This book tells the story of the historical development of calculus through stories about famous problems involving maxima and minima. It includes the story of the Brachistochrone problem.

Ekland, Ivar. The Best of All Possible Worlds: Mathematics and Destiny. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

This book tells the history of seventeenth and eighteenth century mathematics as a story about the quest for optimization.

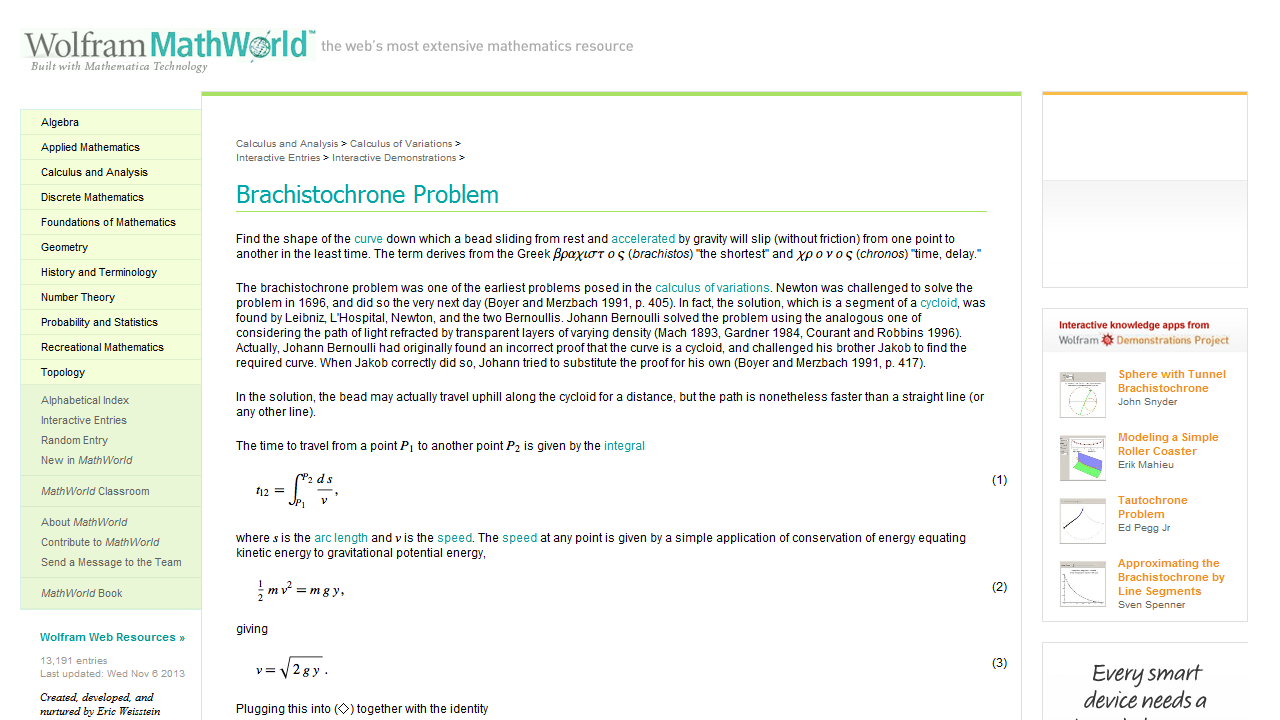

This page from Wolfram Math World provides an advanced discussion of the history and mathematics behind the brachistochrone problem. The full calculus of variations derivation of the cycloid curve can be found here.

This article from the National Science Foundation describes Frank Morgan’s work on the Double Bubble conjecture.