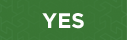

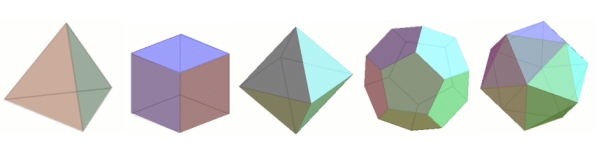

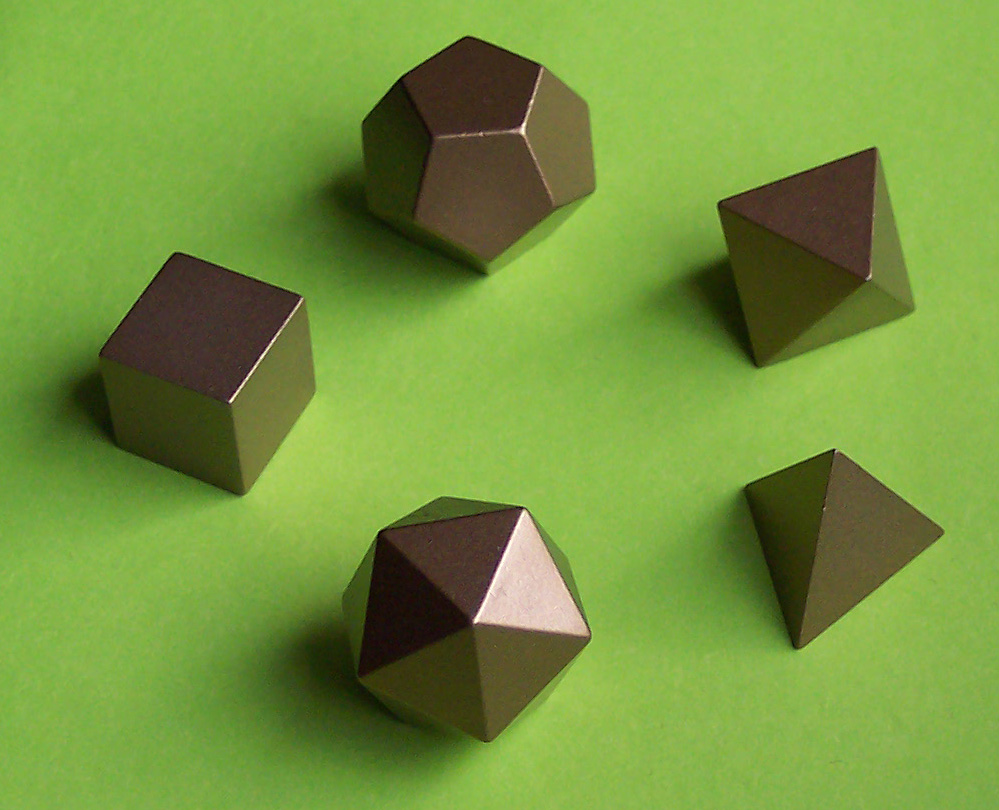

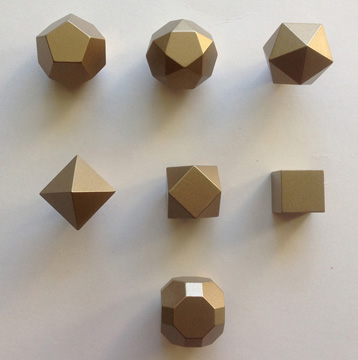

You may be familiar with many of the simple solids you can start with at The Mathenaeum. There are the Platonic solids, named for the Greek philosopher who saw them as the most perfect of all forms. Their polygon faces are regular (same edge lengths, same angles), all faces have the same shape and size, and every face meets at the same angle at the corners. Choose a tetrahedron (4 triangle faces), cube (6 square faces), octahedron (8 triangle faces), dodecahedron (12 pentagon faces) or icosahedron (20 triangle faces). There are also the prisms, the antiprisms, and the pyramids, all with 2 kinds of regular polygon faces.

You may not be familiar with the beautifully complex shapes you’ll make, though! Slice off corners, hollow out and rotate faces, build star-like points, explode or contract. See what interesting solids you can create by making the simplest transformations.

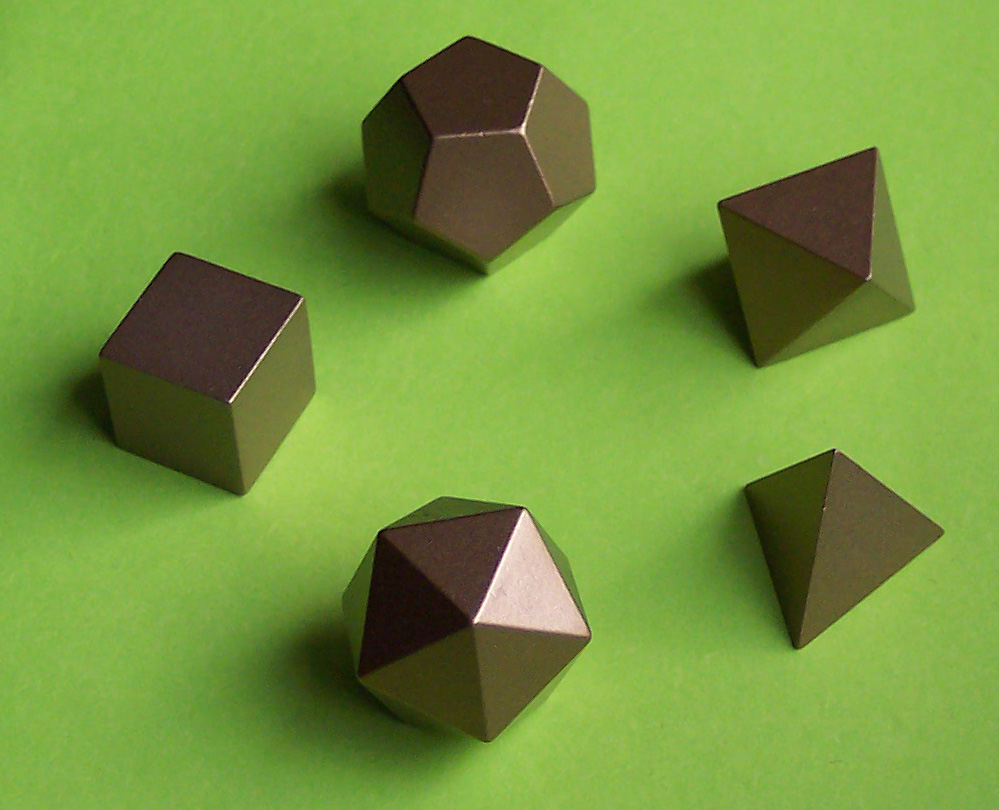

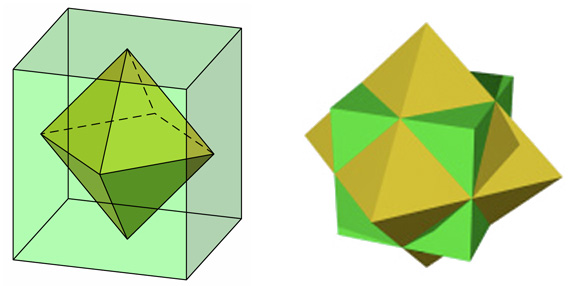

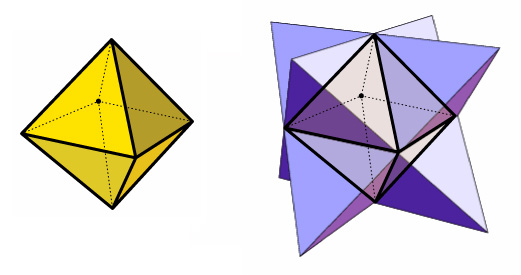

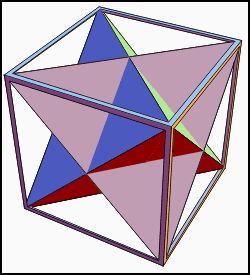

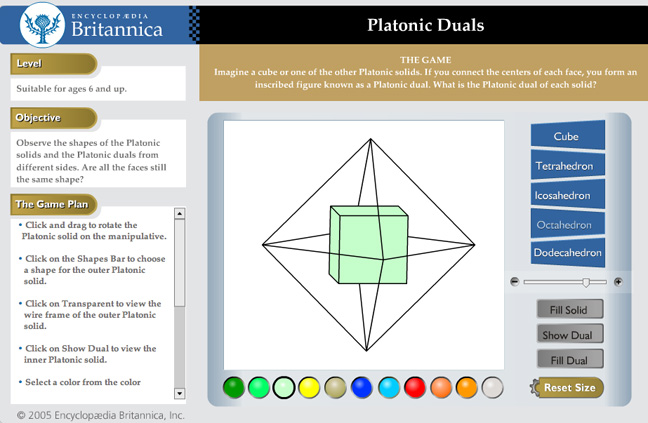

Look at the cube and the octahedron. Imagine placing the octahedron inside the cube so that each corner of the octahedron touches (or pierces) the center of a square face of the cube. Do the number of faces of the cube and corners of the octahedron match up so you can do this? Try counting the edges of each of these solids. What do you notice? Platonic solids that “match up” like this are called duals.

Now count the faces, edges, and corners of the other Platonic solids. Can you pair each with its dual?

Start with the cube and slice off each corner the same way—you just truncated the cube. Cutting off a corner creates a new face. What shape is it? What happened to the old square faces? Now truncate the octahedron the same way. What shapes are the new faces?

Slice so that the new faces are regular polygons, with all edges equal. Truncating any of the Platonic solids can create new solids with regular polygon faces. The picture shows how the cube and the octahedron can be truncated into the same solids (the one in the center is called a cuboctahedron). Pick another solid and truncate!

Have you ever counted faces (square sides), vertices (corners), and edges on a cube? It has 6 faces, 8 vertices, and 12 edges, Count the faces, vertices and edges on a tetrahedron. On an octahedron. Do you notice any relationship between these three numbers for each of the solids? Leonhard Euler noticed that the sum of the number of faces and vertices always is 2 more than the number of edges: v + f = e + 2. This formula is true for any convex polyhedron! Now you can count the number of faces and vertices of a dodecahedron or icosahedron and subtract 2 to find how many edges they have—no counting necessary!

Why are there only five solids that satisfy all of the conditions of regularity? Euclid gave a convincing argument in Book XIII of The Elements. Here is the gist of the argument. For a solid to have all solid corners exactly the same, the angles of the congruent regular polygons that meet at that corner must add to less than 360o. So, starting with equilateral triangles (60o angles), how many triangles can meet at a corner? How many squares can meet at a corner? How many regular pentagons (108o angles) can meet at a corner? Why can’t regular hexagons (or regular polygons with 7 or more sides) make up a corner? So there can’t be more than 5 solids that meet the “corner” test. And each of these five can be built with all corners alike, so there are exactly 5.

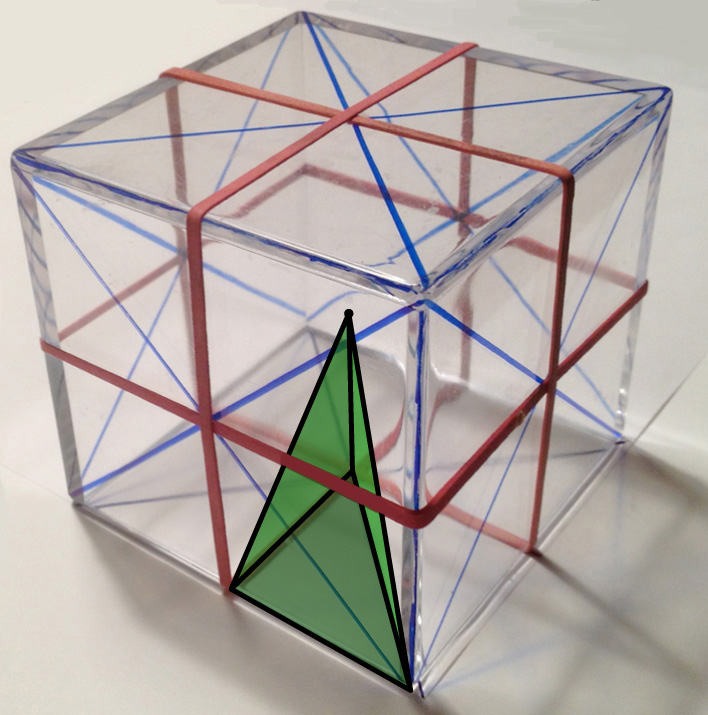

How many ways can you cut a cube exactly in half with a flat mirror so that the two parts reflect onto each other? The mirror is a reflection plane, and the reflection is a reflection symmetry. Reflection planes divide the cube into 48 tetrahedra, all the same. Reflection planes of the cube are outlined in the picture, and one tetrahedron displayed. The cube also has rotation symmetries; it can be partially turned around an axis that pierces through its center and then look as though no turning took place. Where are the rotation axes located on the cube? What is their least angle of turning? Can you find reflection and rotation symmetries of other Platonic solids? Some symmetries of the Platonic solids are shown in the Escher-decorated models.

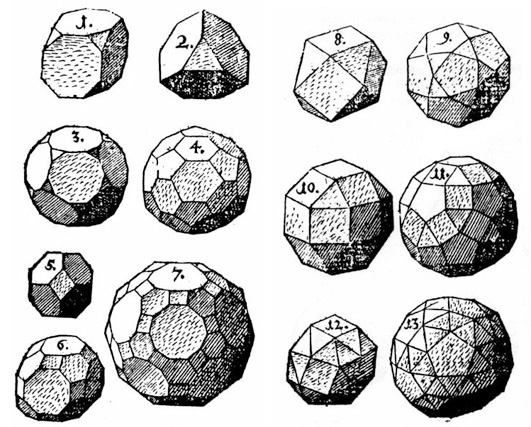

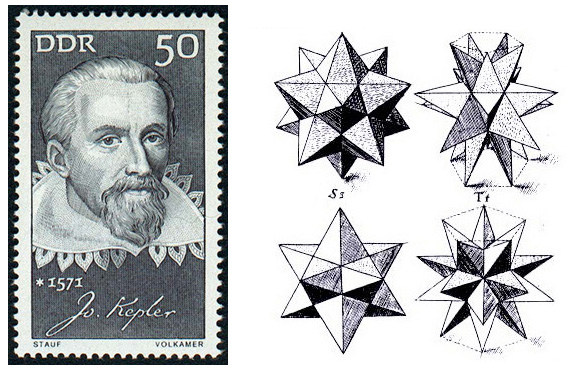

A semiregular, or Archimedean solid has two or more kinds of regular polygon faces but has all of the other “sameness” qualities of the Platonic solids. Most can be produced by truncating a Platonic solid. Although they were known to Archimedes, it was Kepler, several centuries later, who proved there are just 13 such solids, along with the families of prisms and antiprisms. Kepler’s drawings of the 13 Archimedean solids shown here are from his treatise Harmonices Mundi (The Harmony of the World, 1619). Look at the drawings– which ones can you get by truncating a Platonic solid? The second picture gives some ideas.

If you choose the octahedron and imagine each triangle face expanding outwards, something magical happens when the extended faces intersect. At that moment, a new star-shape appears, called a Stella Octangula. This process of growing the faces of a polyhedron outward until they intersect is called stellation— it can create a star-like form. Try it with the dodecahedron. Try it with the icosahedron. What happens when you try it with the cube? The tetrahedron?

This exhibit lets one play with building various polyhedra, in all their beauty, and combinatorial complexity. The corners of a polyhedron, together with the edges between them, form what mathematicians call a “graph,” the study of which was arguably initiated in Leonhard Euler’s solution in 1736 to the “Königsberg Bridges” problem (about whether it is possible to walk through that famed city, crossing each of its bridges exactly once). In the centuries since graph theory’s humble origins, it has grown to a full-blown field in its own right, with far-reaching applications to networks, statistical physics, biology, and much, much more. Professor Maria Chudnovsky of Princeton University is a world expert in graphs and combinatorics, having contributed to solutions of some of the most long-standing problems in the business. Her work was recognized by many awards and accolades, including a Clay Research Fellowship, and, in 2012, a MacArthur “Genius Grant.”

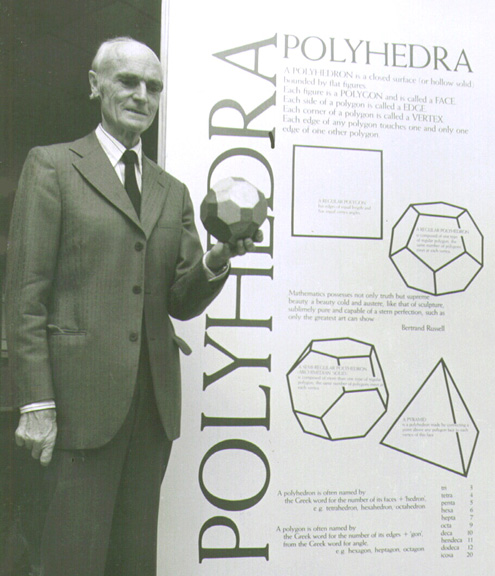

Harold Scott MacDonald Coxeter, a professor at the University of Toronto for 60 years, was one of the foremost geometers of the 20th century. He was devoted to researching and teaching all aspects of geometry and is especially noted for his work on regular polytopes. Regular polytopes are the regular polygons in the plane, regular polyhedra in 3-space, and their higher-dimensional counterparts. in his lifetime, he had more than 200 publications on subjects in geometry. Two that are directly related to polyhedra in the Mathenaum are The 59 Icosahedra (the various stellations of the icosahedron), 1938, and Uniform Polyhedra, 1954.

George Hart is a mathematical artist who uses his computer science knowledge to create geometric sculptures based on polyhedra. He creates imaginative forms buildable in “barnraising” events in which groups assemble the structures from like pieces. He also “prints” with a 3-d printer, creating sculptures that would be impossible to build by hand. His web site is rich with information about all the symmetric polyhedra (Encyclopedia of Polyhedra), as well as his sculptures, publications, and hosted events. His puzzle-sculpture “Frabjous” is sold in the Museum shop.

Fr. Magnus Wenninger is a Benedictine monk who has devoted his life to teaching mathematics, making geometric models, and sharing his knowledge about polyhedra and model-making through wonderful presentations and books accessible to anyone who wants to see and feel the beauty of symmetric polyhedra. See References for his books.

Ernst Witt was a German mathematician who taught at the University of Hamburg. He studied finite reflection groups, subclasses of which are groups that describe the symmetry of platonic solids using a more algebraic description.

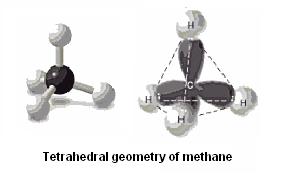

An action on an object that leaves the image unchanged is called symmetry. In chemistry, the symmetry of molecules is used to classify and study their behavior. From the symmetry of a molecule, a chemist can predict or explain many of the chemical’s properties. Molecules that have symmetries equivalent to the symmetries of the platonic solids are special because they can be rotated on several axes with the image remaining unchanged. An example of a molecule with the same symmetries as a tetrahedron is the methane molecule shown here. Can you see the resemblance between methane and the tetrahedron?

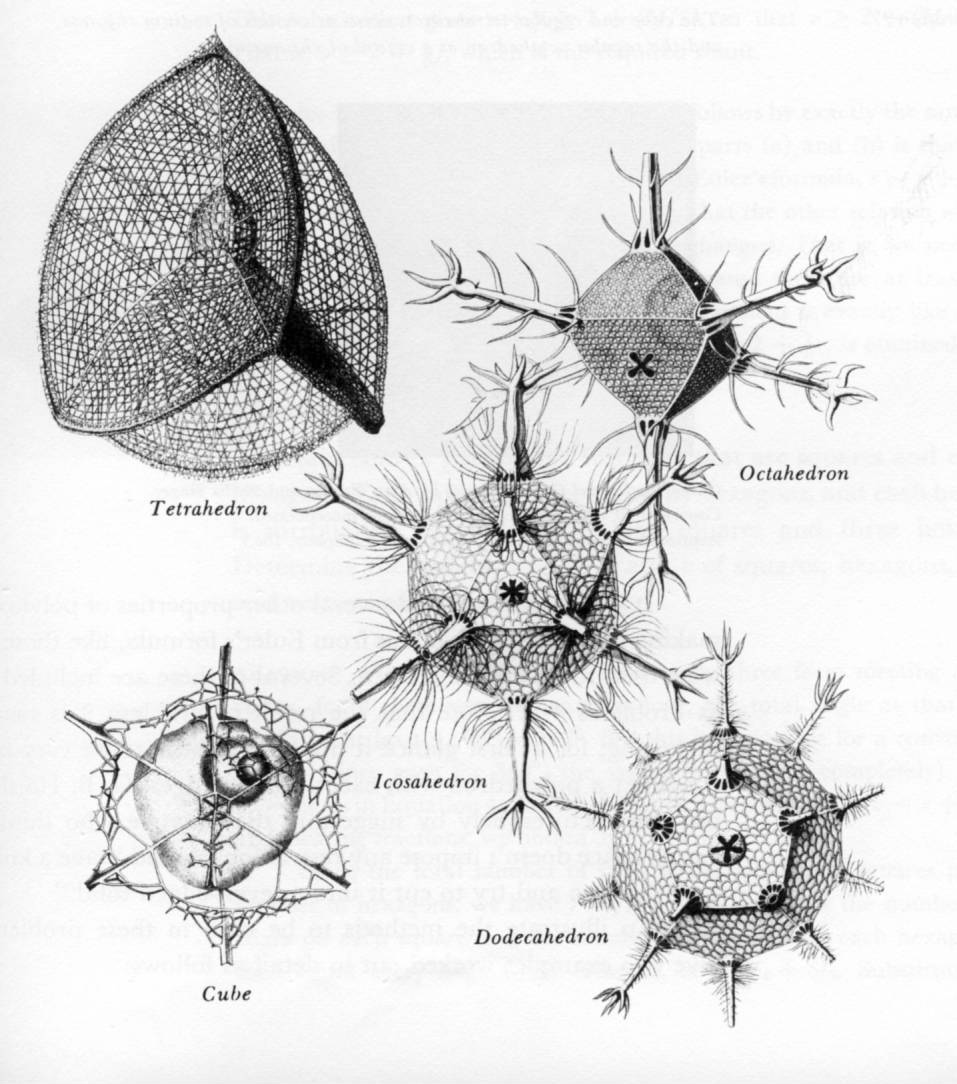

One surprising place where Platonic solids can be found in nature is in a minute marine life form called a radiolarian. These are mineral skeletons of single-celled life forms. They were discovered by Ernst Haeckel on a sea expedition in 1873-1876. His careful drawings show that a number of species of radiolaria were shaped like the Platonic solids. Some examples include Circoporus octahedrus, Circogonia icosahedra, Lithocubus geometricus and Circorrhegma dodecahedra. Their names identify the Platonic solid for which they are named. The illustration is taken from several plates in Haeckel’s Report on the Scientific Results of the voyage of H.M.S.Challenger, vol 18, London 1887.

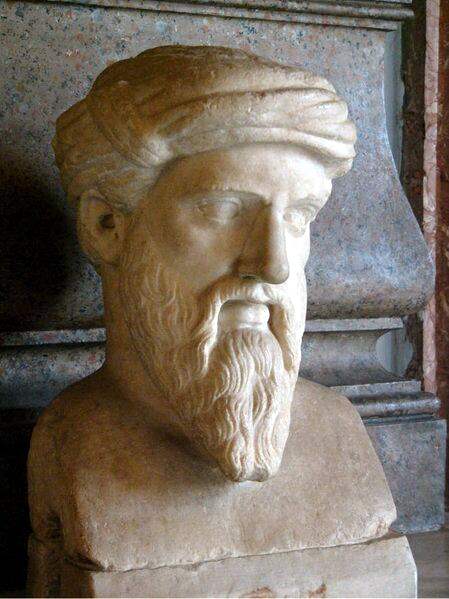

The history of Platonic solids has some debate. The historian Proclus (411-485 CE) gives credit to Pythagoras of Samos for their discovery. Pythagoras (ca. 570 BCE – 495 BCE) lived more than a century before Plato. Many have learned the famous Pythagorean Theorem that led to the discovery of irrational numbers. What you might not have known is that Pythagoras had a group of followers called the Pythagoreans. These individuals were among the first to discover that not all numbers could be represented as a rational number (i.e a quotient of two integers). The Pythagoreans may only have been familiar with the tetrahedron, cube, and dodecahedron.

The historians that believe that Pythagoras did not know all of the Platonic solids argue that Theaetetus of Athens (ca. 417-369 BC) was the first to discover the octahedron and icosahedron. One of the reasons that Theaetetus is interesting is due to the fact that none of his own writing has survived. What we know about him comes from the writings of Plato. In Euclid’s book Elements, the introduction by Pappus gives credit to Theaetetus for the proof that there are only 5 Platonic solids.

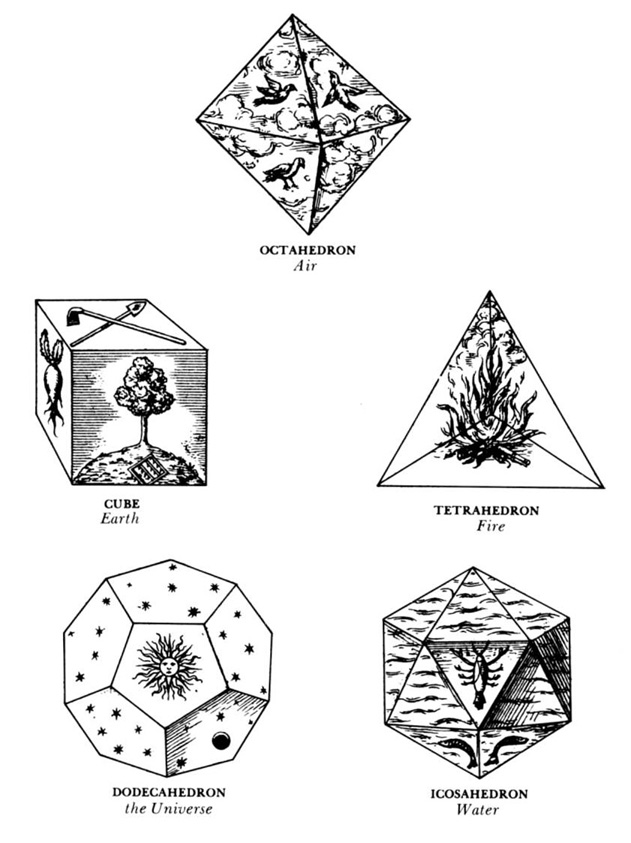

Why are the regular polyhedra called the Platonic solids? The answer is found in the dialogue Timaeus (ca. 350 BCE) by the Greek philosopher Plato, who revered perfection of form. He theorized that the classical elements (fire, air, water and earth) were constructed from these regular solids. The tetrahedron represented fire (fire feels sharp and stabbing like a tetrahedron). Air is made of the octahedron, water the icosahedron, and earth the cube. With no classical element for the dodecahedron, he obscurely remarks “the god used [this] for arranging constellations on the whole heaven”. Thus the dodecahedron can represent the universe. Johannes Kepler illustrated these assignments his 17th century treatise Harmonices Mundi.

Euclid, sometimes called the “Father of geometry”, lived in ancient Greece around 300 BCE. Much of the early work on Platonic solids is recorded due to the mathematical descriptions contained in Euclid’s Elements. The last book, XIII, is devoted primarily to the properties of these objects and contains an argument as to why there are only 5 regular solids. Many of the results in the Elements were known well before Euclid recorded them; his contribution was to present them in an orderly framework, and to provide mathematical proofs based on axioms. Euclid’s Elements was the basis for almost all geometry texts even until the 20th century.

The famed astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) was the first to mathematically investigate solids with regular polygon faces, as well as some of their stellations. He proved there are only 13 Archimedean solids, along with two infinite families of prisms and antiprisms. The “star” solids he derived as stellations of the dodecahedron are named Kepler polyhedra. His drawings of the two stellated dodecahedra (Ss and Tt) shown here are from his treatise Harmonices Mundi , Book II (The Harmony of the World, 1619).

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783, pronounced “Oiler”) was one of the most prolific mathematicians ever, both in breadth of his interests and in his writings (which after more than two centuries, have not yet all been translated into English). He is famous for “Euler’s formula” for all polyhedra deformable to a sphere, that states the sum of the number of vertices and the number of faces of the solid equals the number of edges plus 2: v+f = e+2.

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel was a biologist who studied thousands of species. Among those were very small single-celled life-forms called the Radiolarians. These creatures measure in diameter of 0.1-0.2mm and have extremely intricate skeletons. Some members of this species have shapes that resemble the platonic solids. These include: Circoporus octahedrus, Circogonia icosahedra, Lithocubus geometricus and Circorrhegma dodecahedra. It was Ernst Haeckel’s drawings in his book Die Radiolarien (Berlin, 1862) that helped to popularize these creatures and spurred further study.

The Heart of Mathematics: An Invitation to Effective Thinking, by Edward Burger & Michael Starbird, Wiley (second edition 2005) is a textbook with a nice section on Platonic Solids (Section 4.5)

Platonic Duals, on the Encyclopedia Britannica web site http://kids.britannica.com/lm/manipulatives/enu/workspaces/platonic_duals/product.html is a nice interactive demonstration of duality of the Platonic solids.