Some shapes fit together just right, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Squares, triangles, and hexagons can do this, and sometimes even monkeys, dinosaurs, and bunnies!

What patterns can you make by arranging a handful of similar tiles edge to edge, without gaps or overlaps? What if you used more than one type of tile?

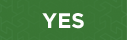

The simplest way to tile a plane is with just one shape of tile, and the simplest types of tiles are the ones that have same-length edges and equal angles, like the “regular” triangles, squares, and hexagons shown here.

It turns out triangles, squares, and hexagons are the only three regular polygons that tile the plane, because they are the only ones we can pack around a point with no gaps or overlaps.

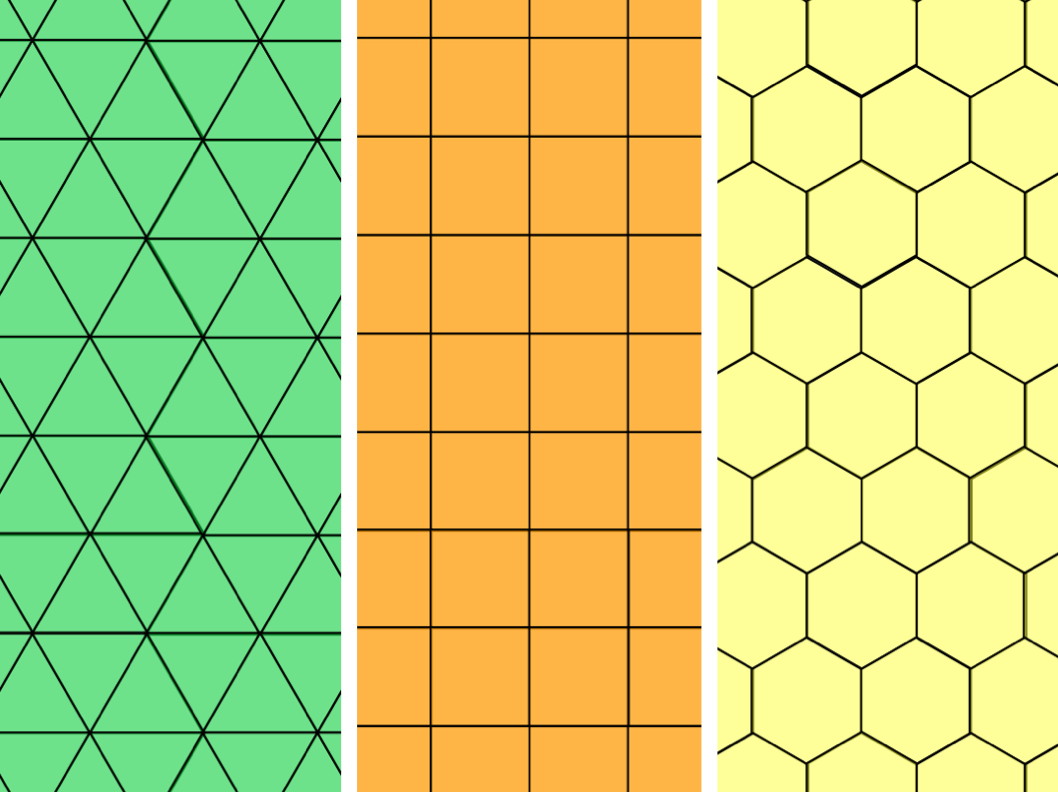

A pattern of tiles that touch at a single point is called a star. If you can go all the way around a point with no gaps or overlaps then you will have something called a complete vertex star.

How many star formations like these can you make? Can all types of tiles make stars?Try beginning a larger pattern with a star you create!

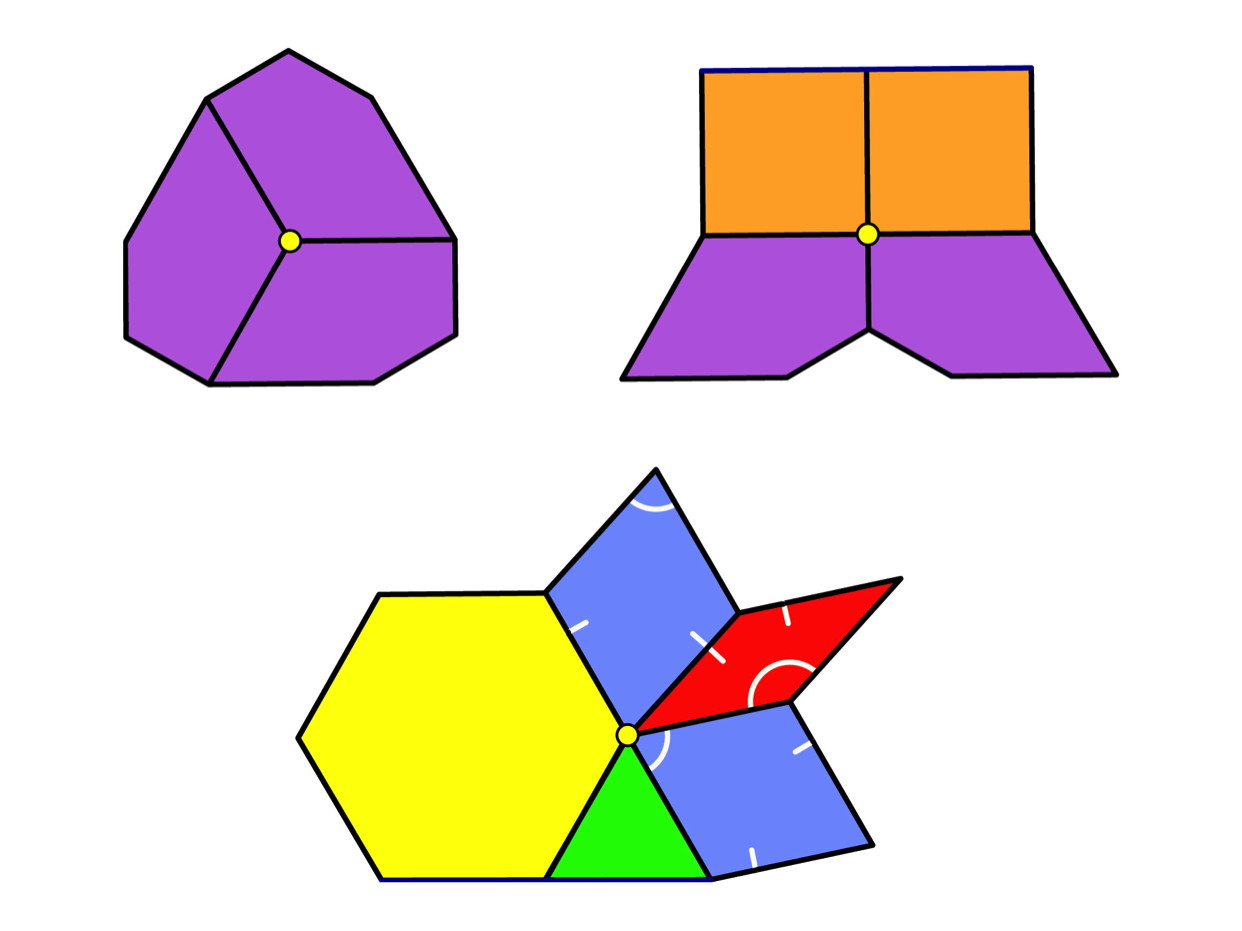

How many ways can you tile the wall if you use more than one type of polygon tile? If all of the vertex stars are required to be the same, then the answer is just eight!

Five of these repeating patterns can be made with the triangles, squares, and hexagons at this exhibit. Can you find them all?

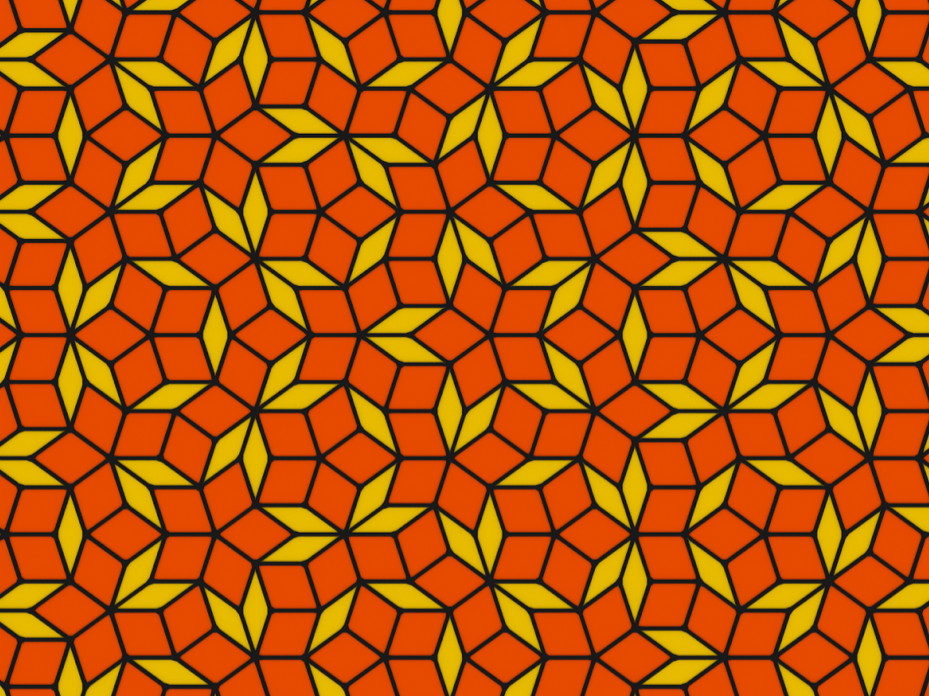

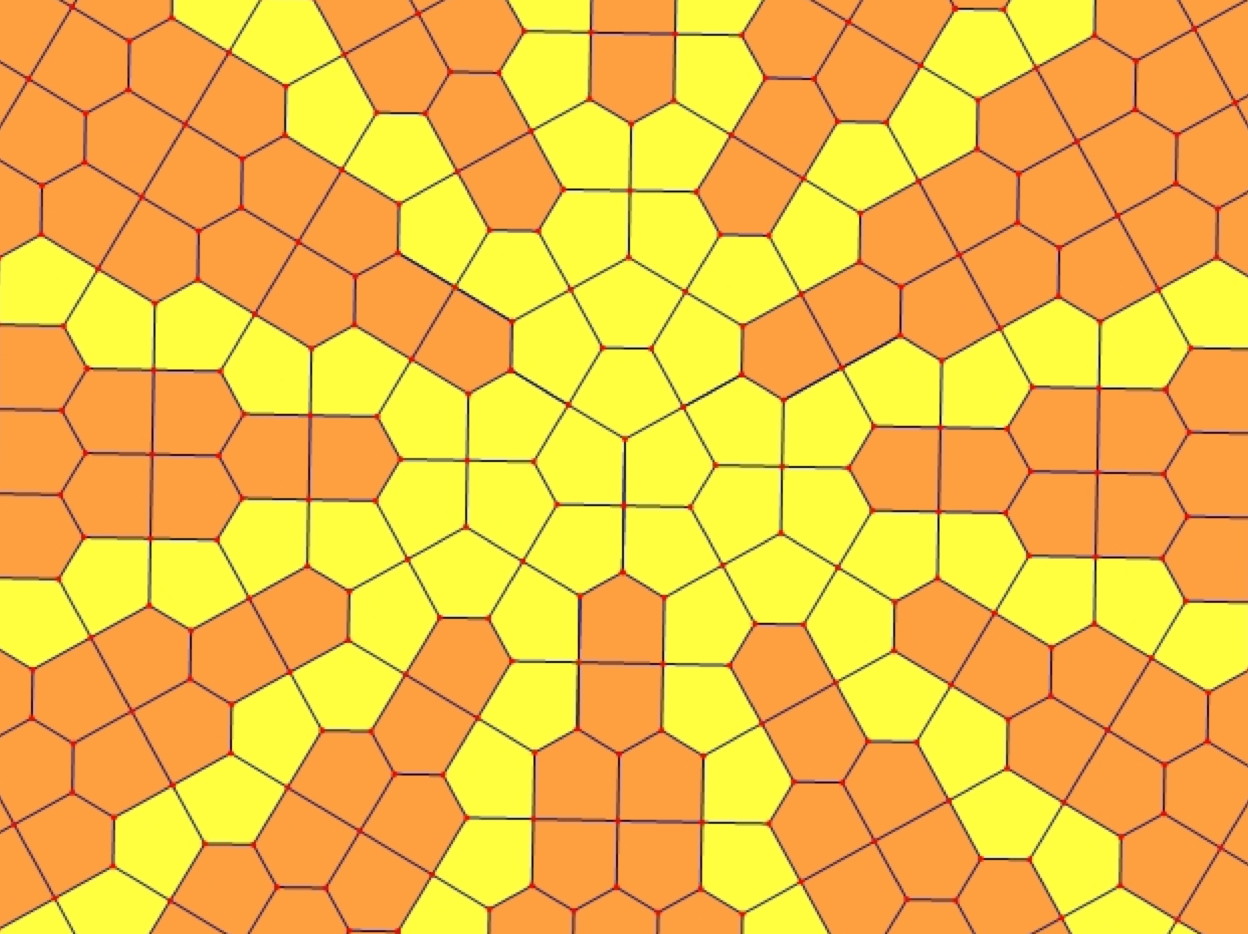

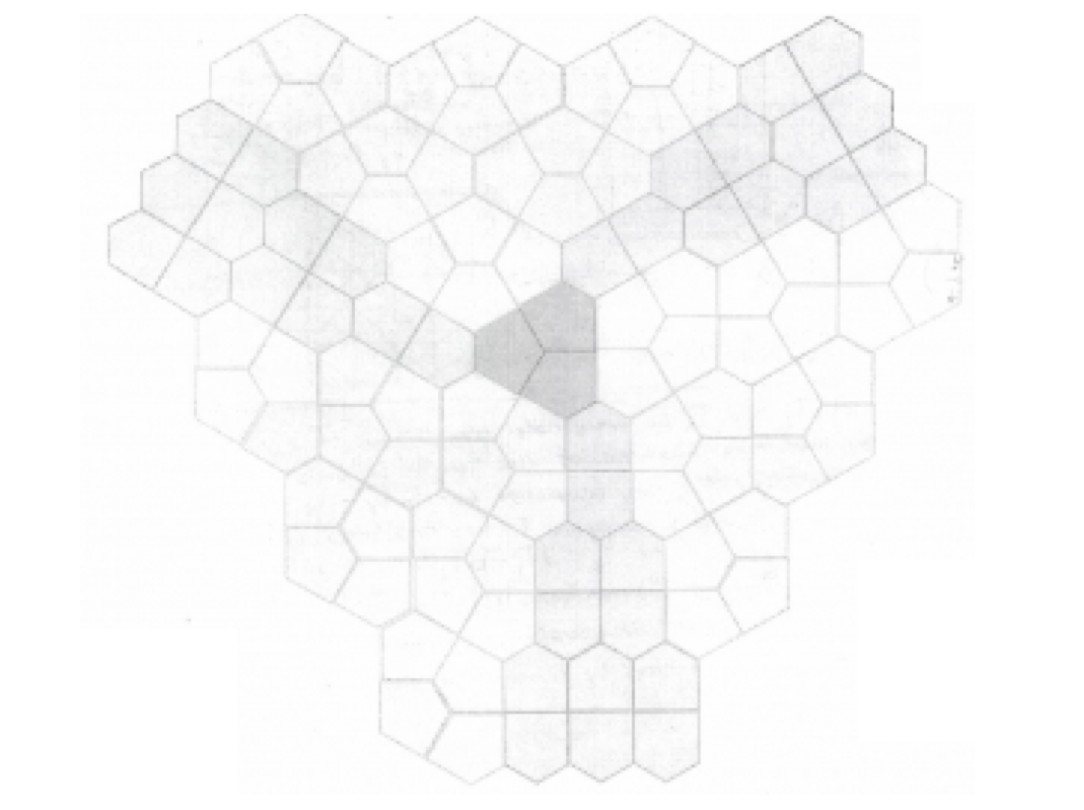

Look carefully at the tessellation in this picture. There is no piece of this pattern that can be repeated by moving up, down, left, or right to make the rest of the pattern.

Try using the thick and thin rhombus tiles to make a pattern. If you match the markings on the tiles then your pattern will have the same lack of repetition as the one shown here, but can still go on forever.

The monkey, rabbit, and dinosaur tiles at Tessllation Station can each cover the whole wall without gaps or overlaps. These clever tiles were designed by the Japanese artist Makoto Nakamura.

Six monkeys can twirl around a fingertip, three monkeys can spin around an elbow, and two monkeys can fit their legs together. Each design is made by removing and adding pieces from polygons.

A regular pentagon, with all angles and sides the same, cannot tile a wall. This is because we can’t fit regular pentagons around a point without either leaving a gap or creating an overlap.

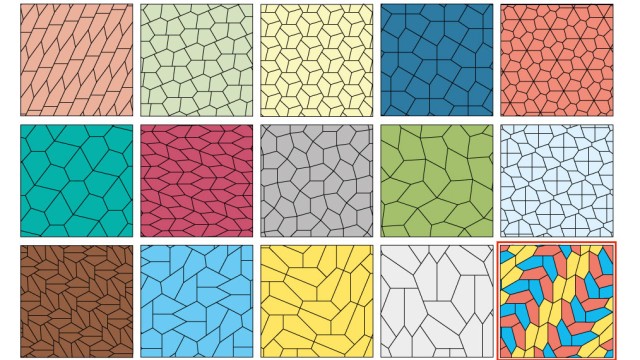

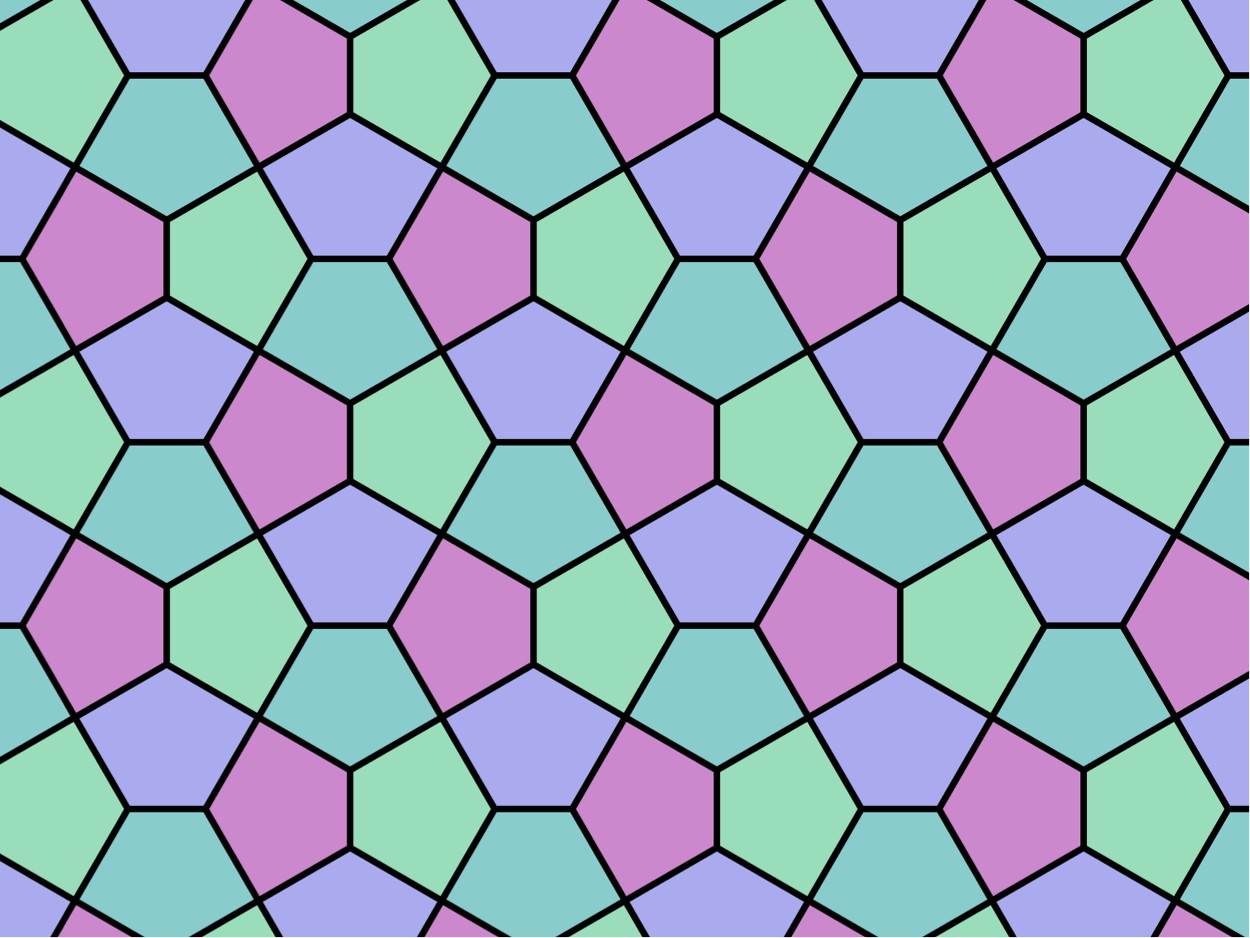

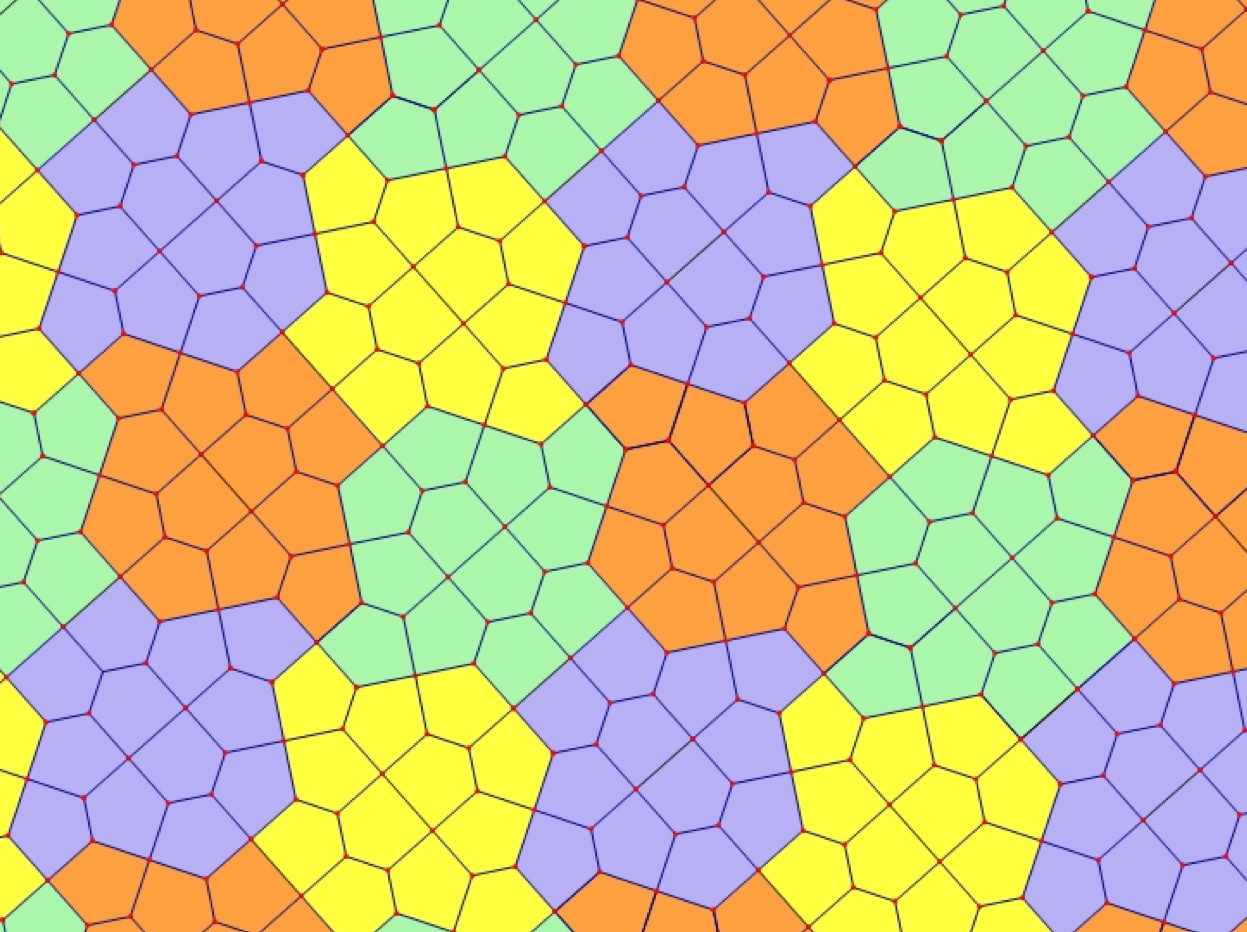

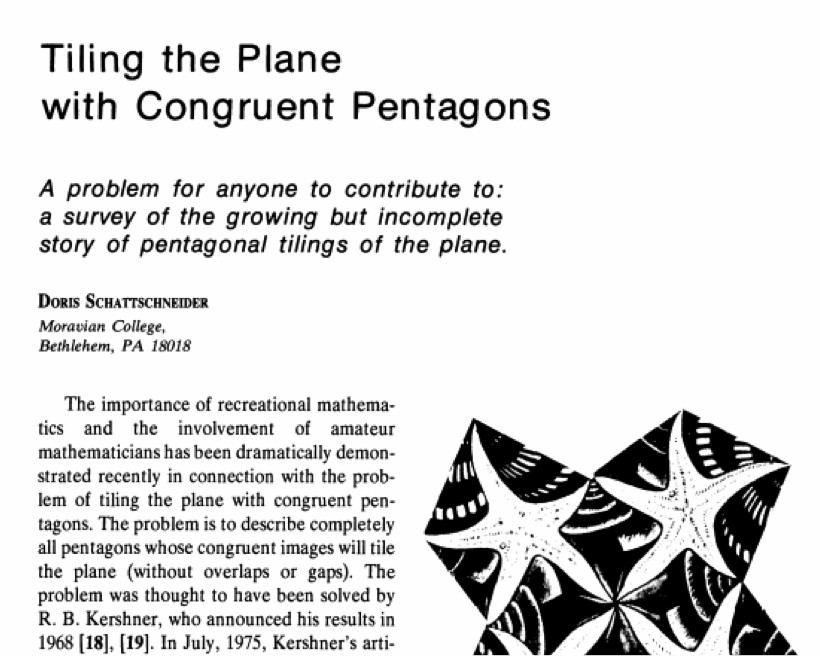

However, we can make five-sided shapes that do tile a wall. In this picture are the 15 known tiling pentagons, nearly half of which were discovered by people who did not study math as their main subject.

The fourteenth tiling was found in 1985 and then no new tilings were found for 30 years. Mathematicians had begun to suspect that the list of 14 tilings was complete, but then a fifteenth tiling was discovered in 2015. In 2017, French mathematician Michaël Rao announced a proof that this list of 15 is complete, and the argument, heavily computer-assisted, is still undergoing peer review.

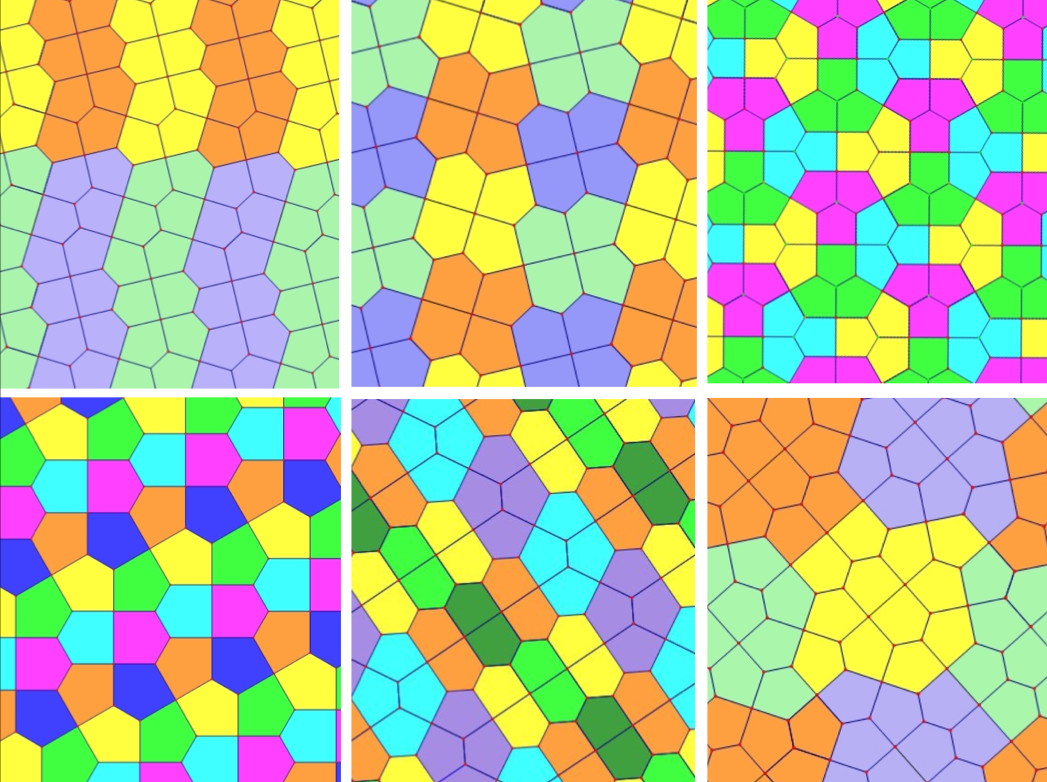

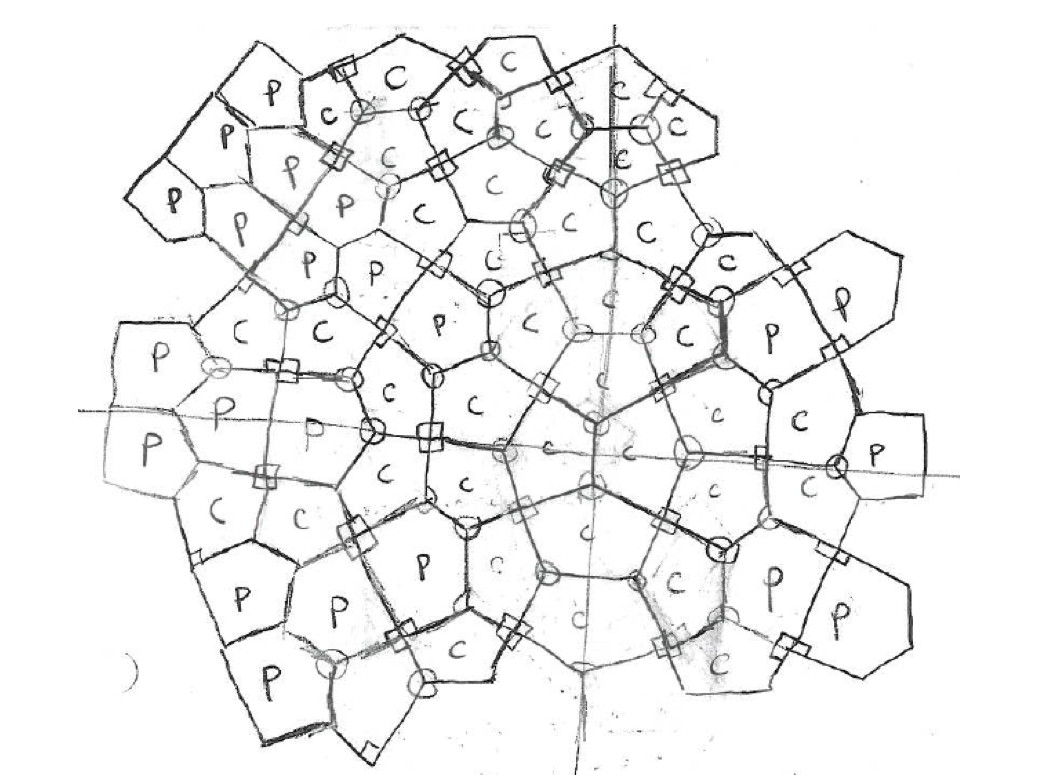

Can you find a new tiling pattern using only the Cairo and Prismatic tiles?

If you find one that is different than the ones shown here and in the Gallery, take a picture! Math is all about discovering new things, and you could create some new math today, right here at MoMath.

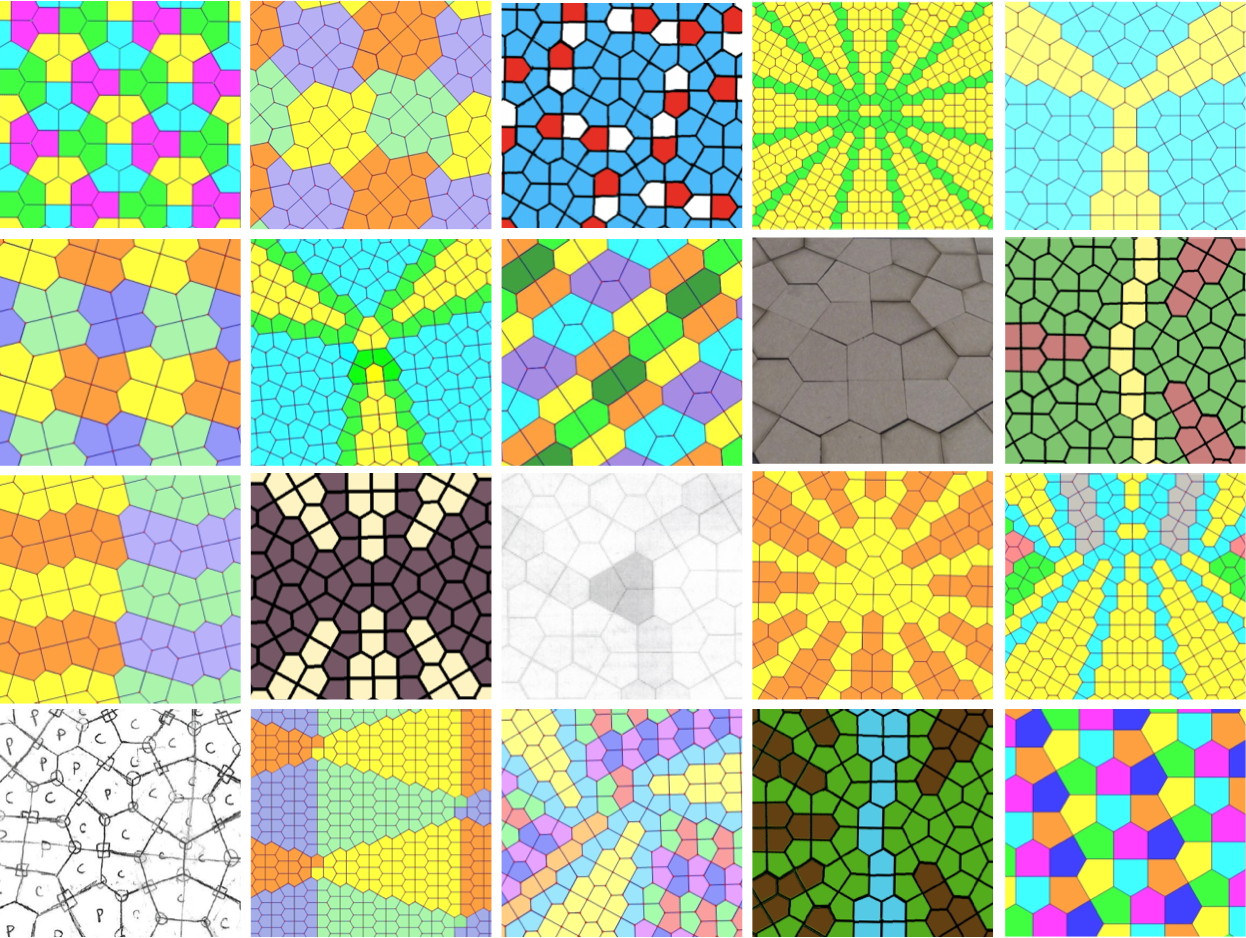

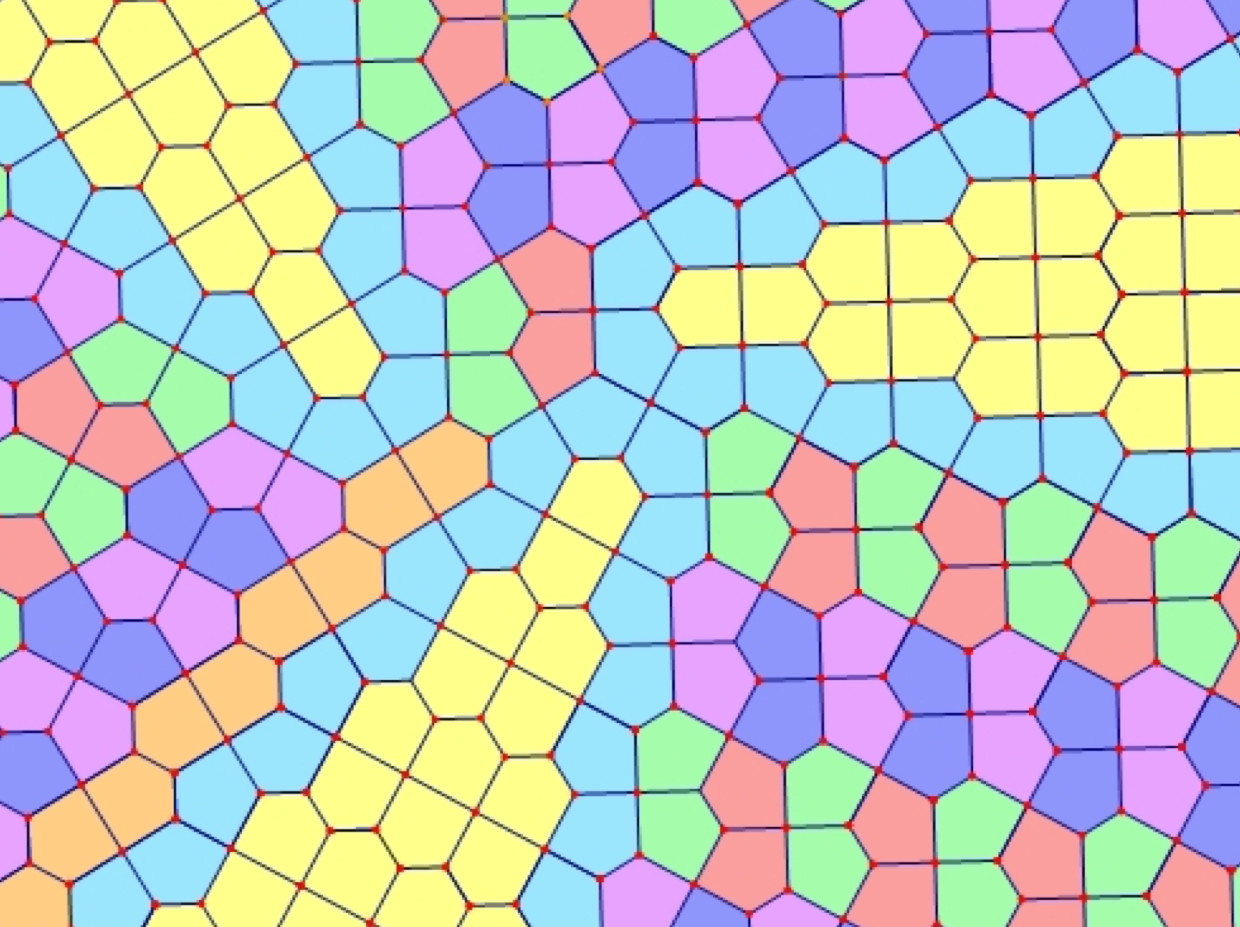

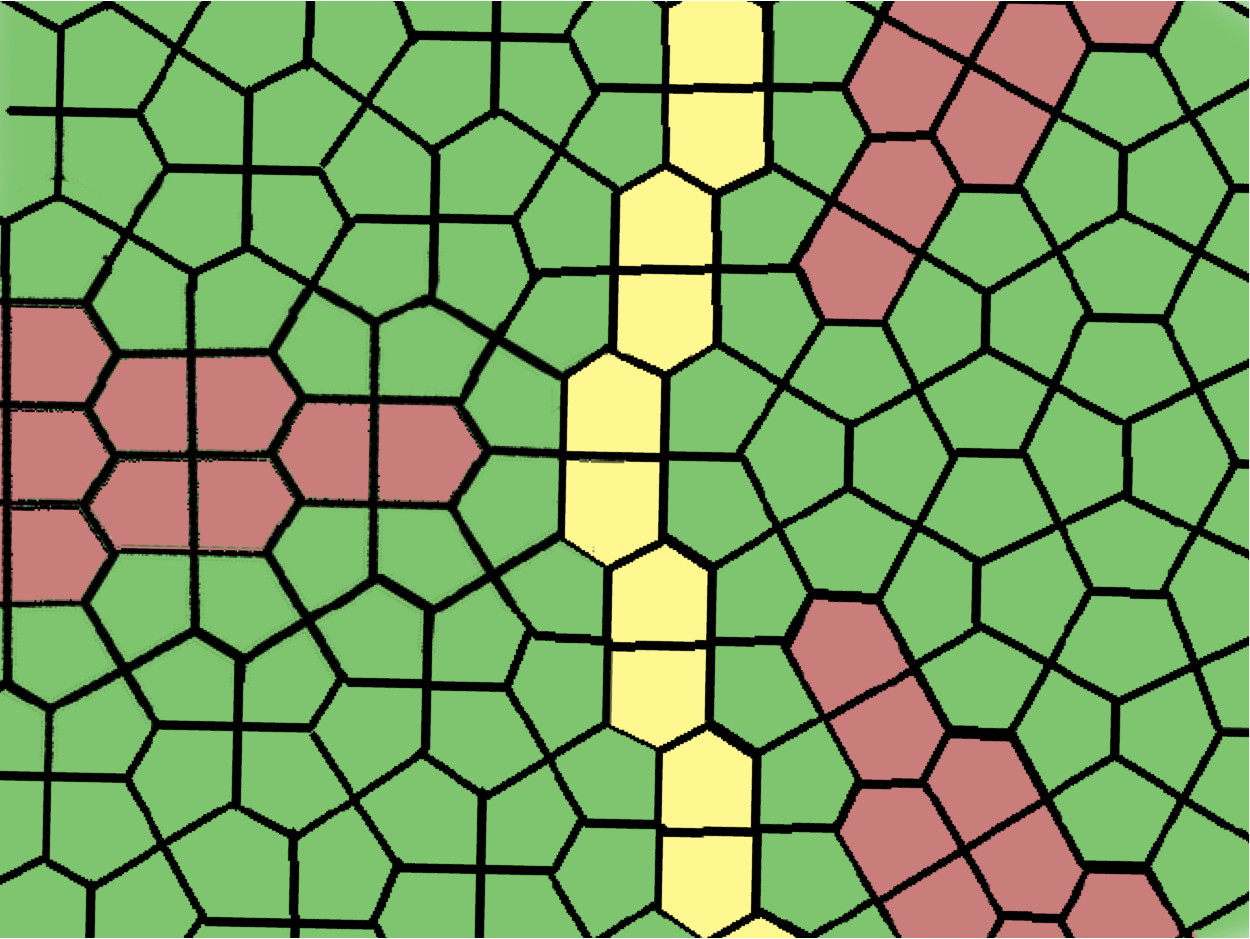

There are many ways to fill the plane with the Cairo and Prismatic tiles. All of the known types of Cairo-Prismatic tessellations are shown in the pictures in this Gallery. Can you find a new one?

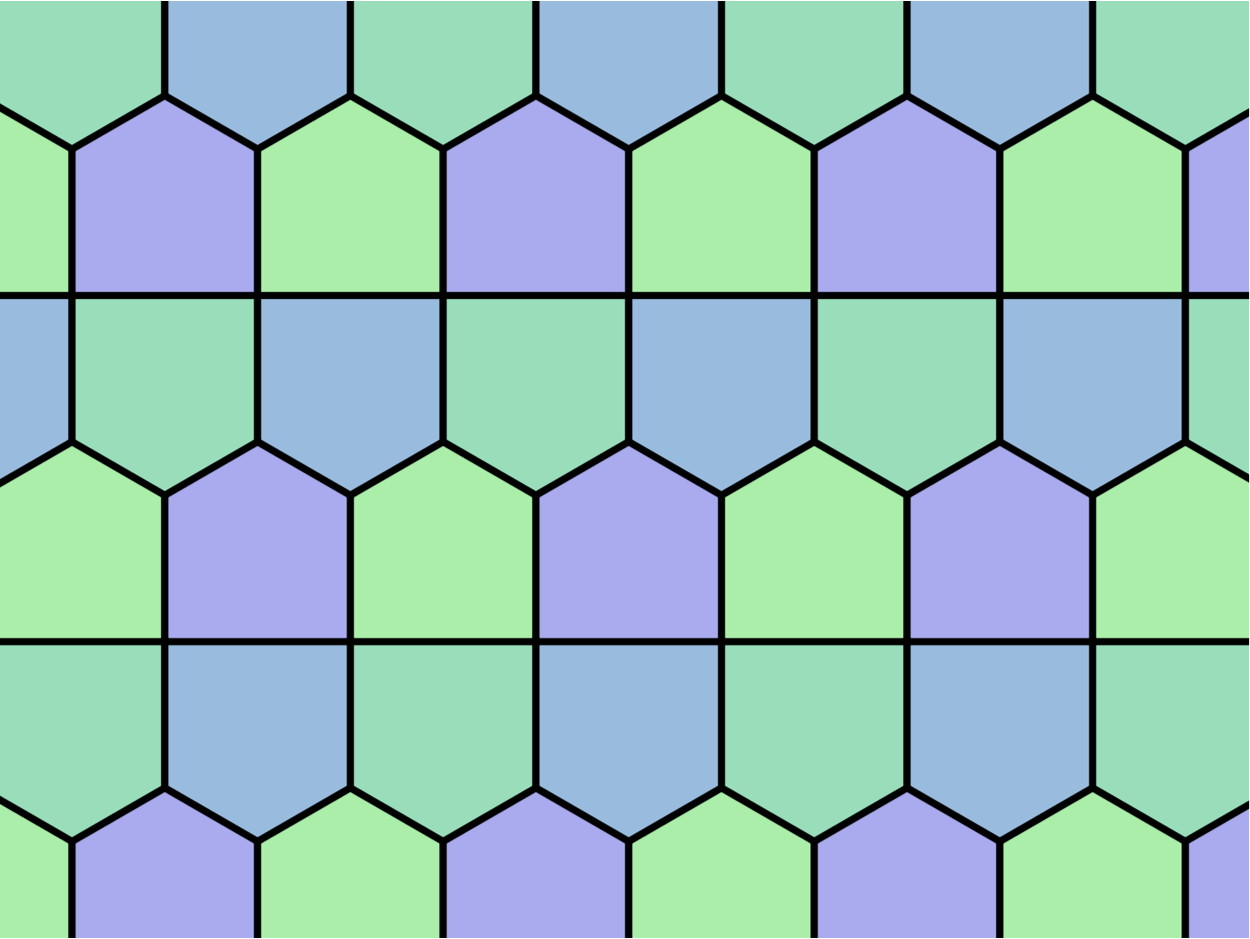

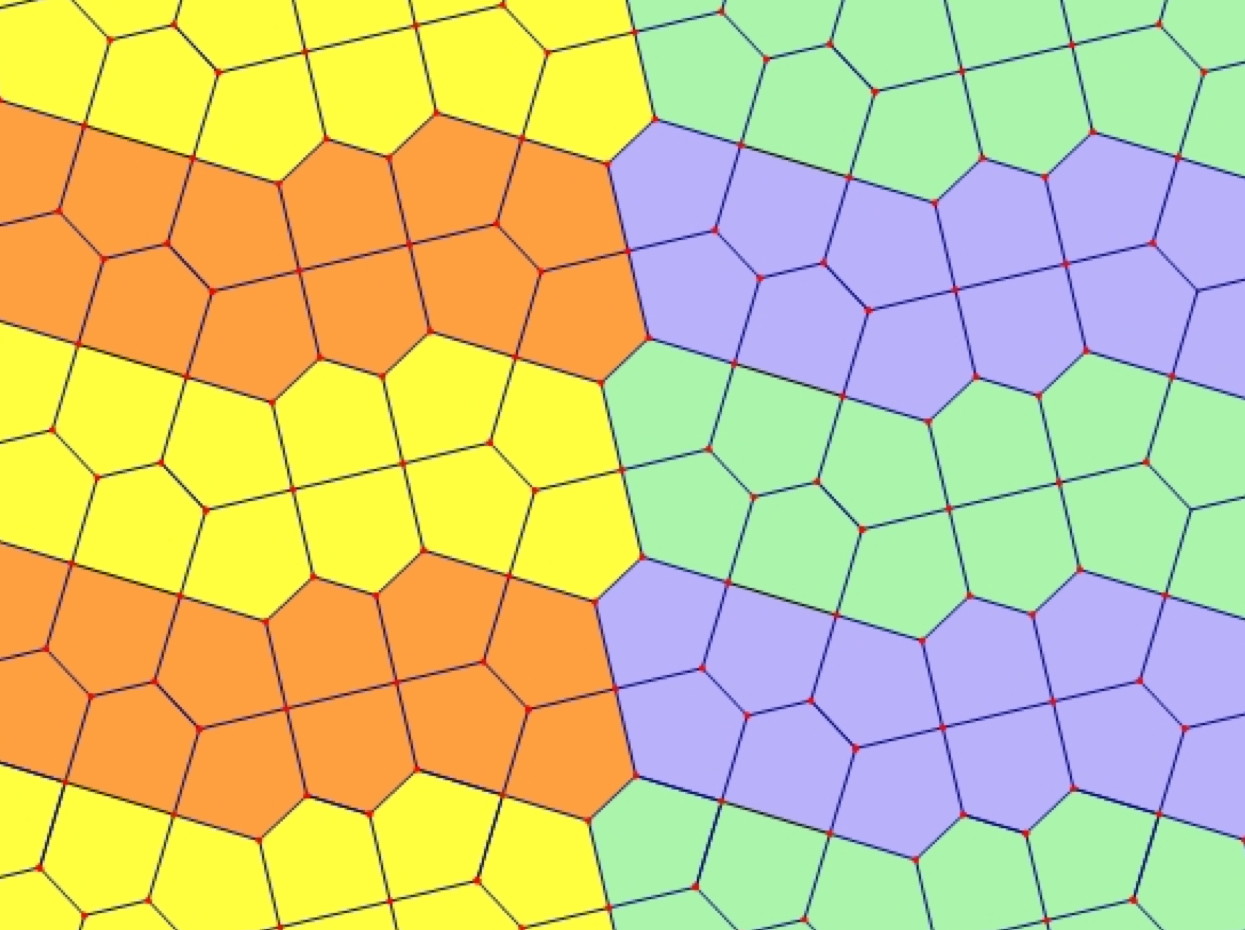

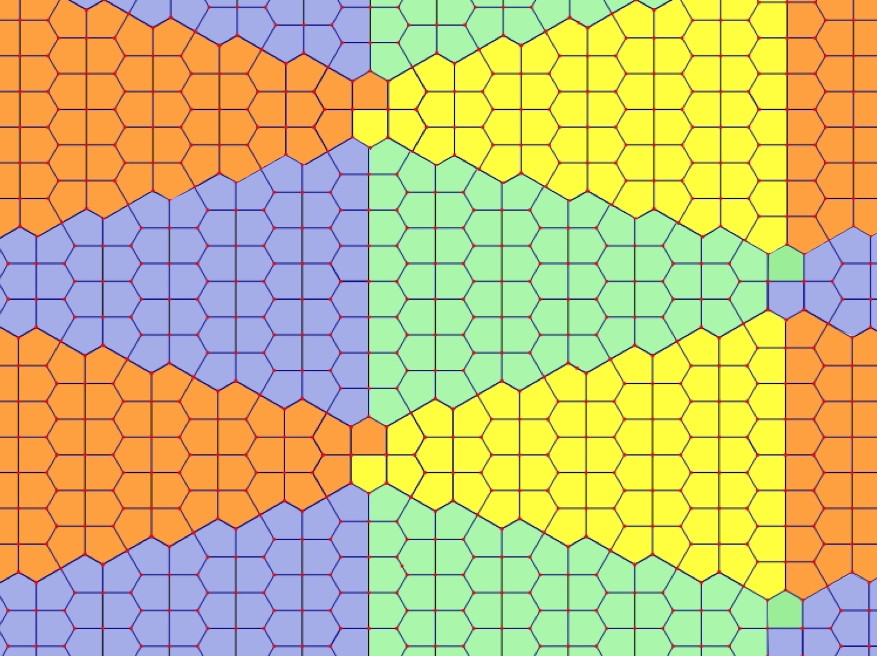

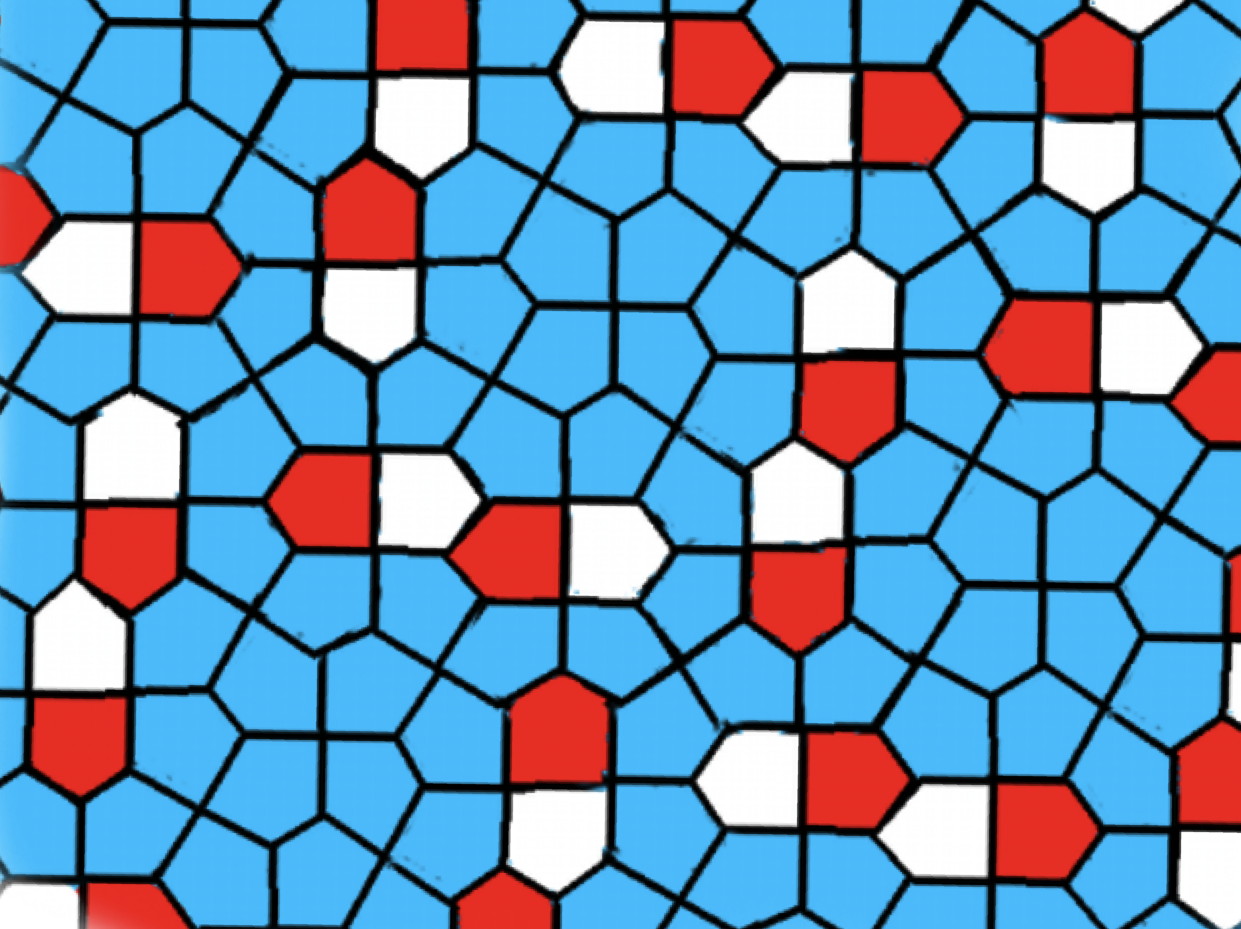

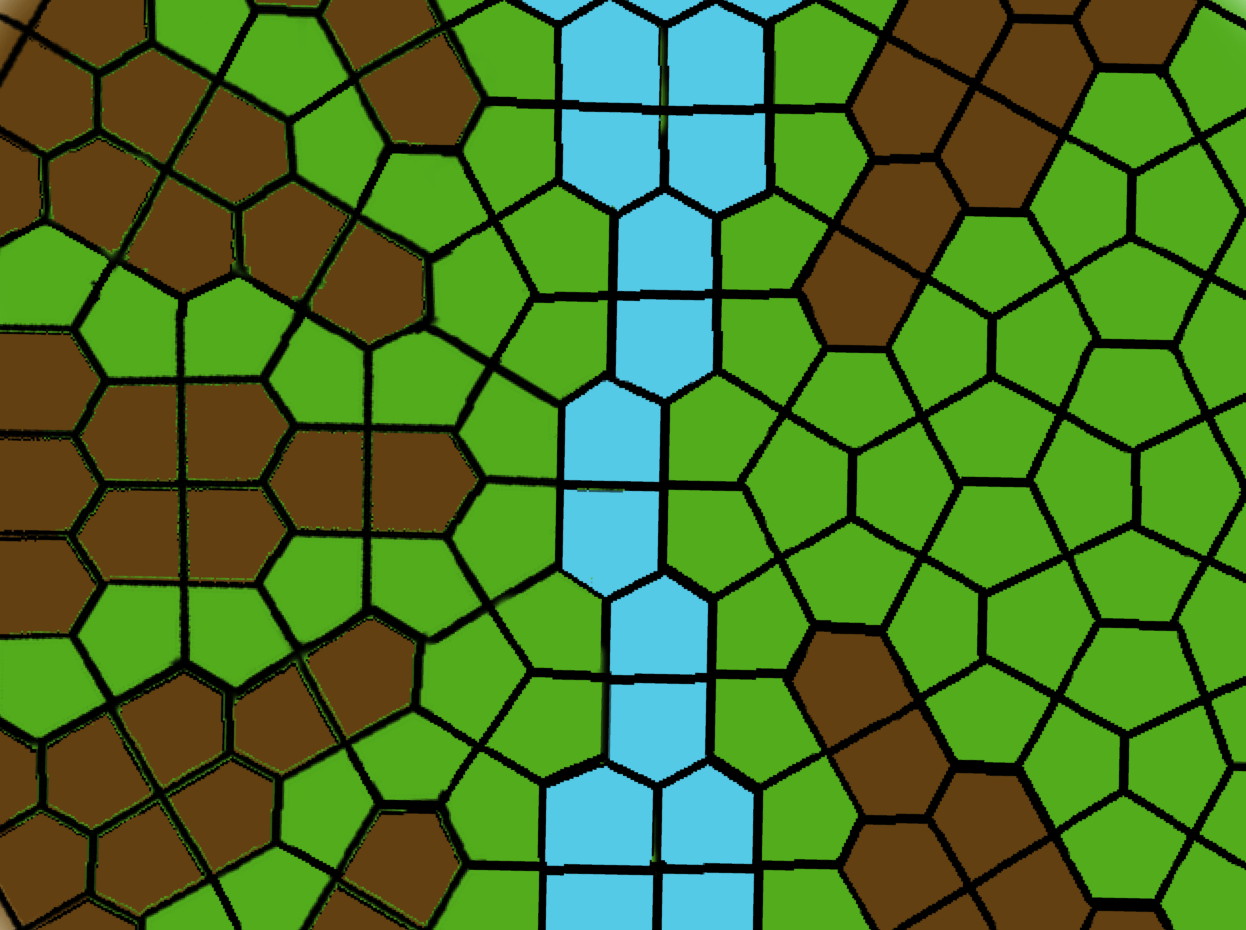

This picture shows the only way to tessellate the plane using just Cairo pentagonal tiles. The Cairo pentagon is one of the two tessellating convex pentagons that minimize perimeter.

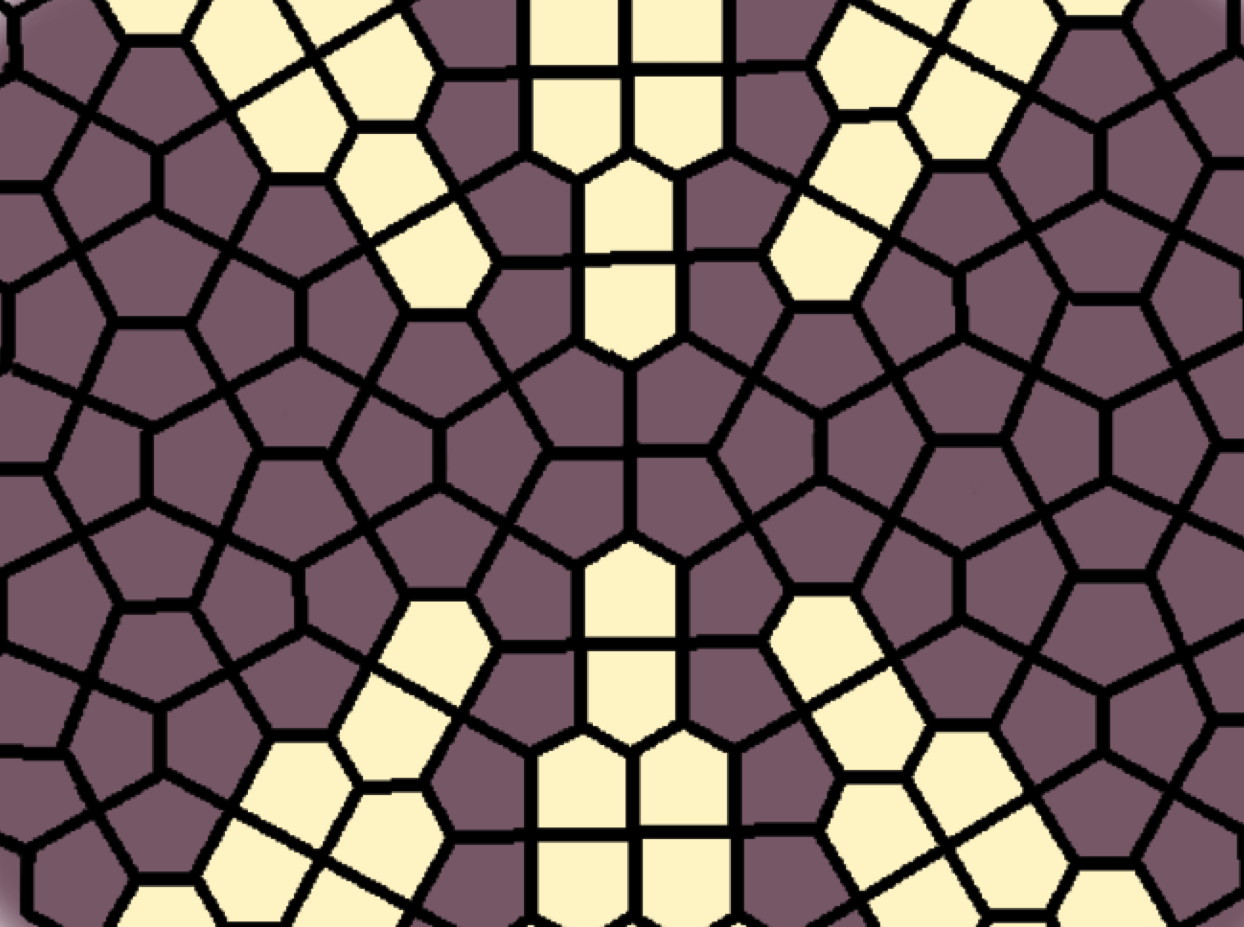

This picture shows the only way to tessellate the plane using just Prismatic pentagonal tiles. The Prismatic pentagon is one of the two tessellating convex pentagons that minimize perimeter.

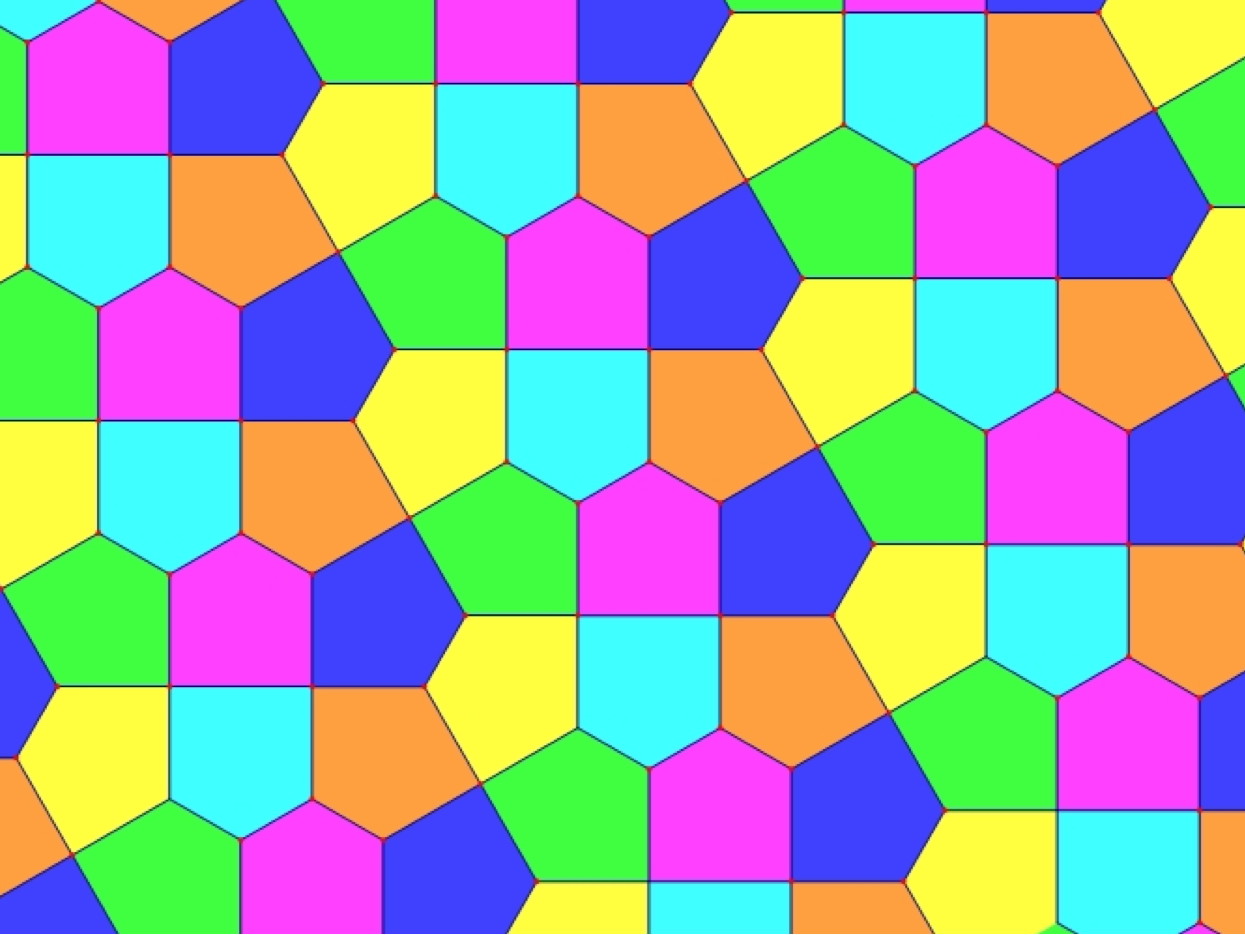

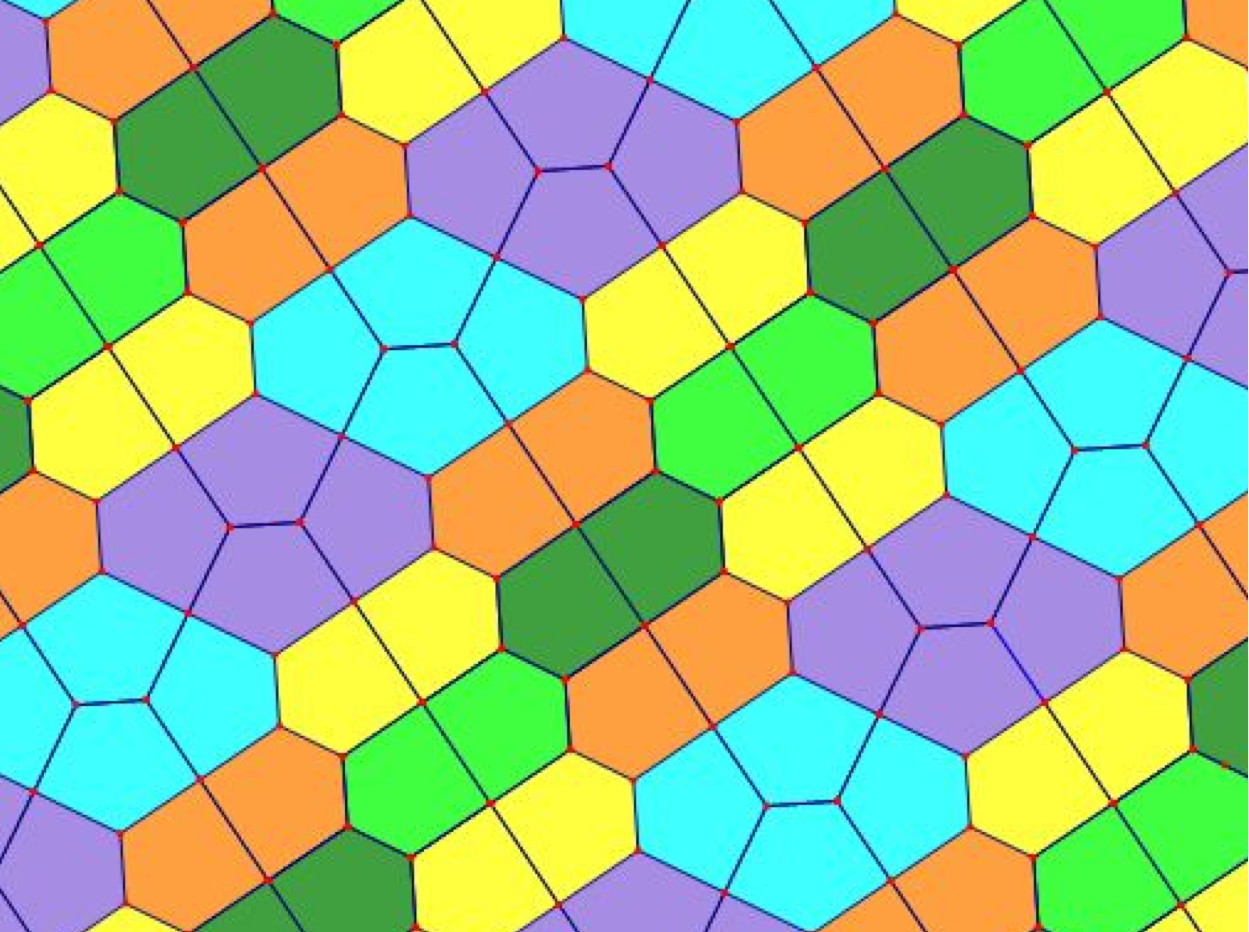

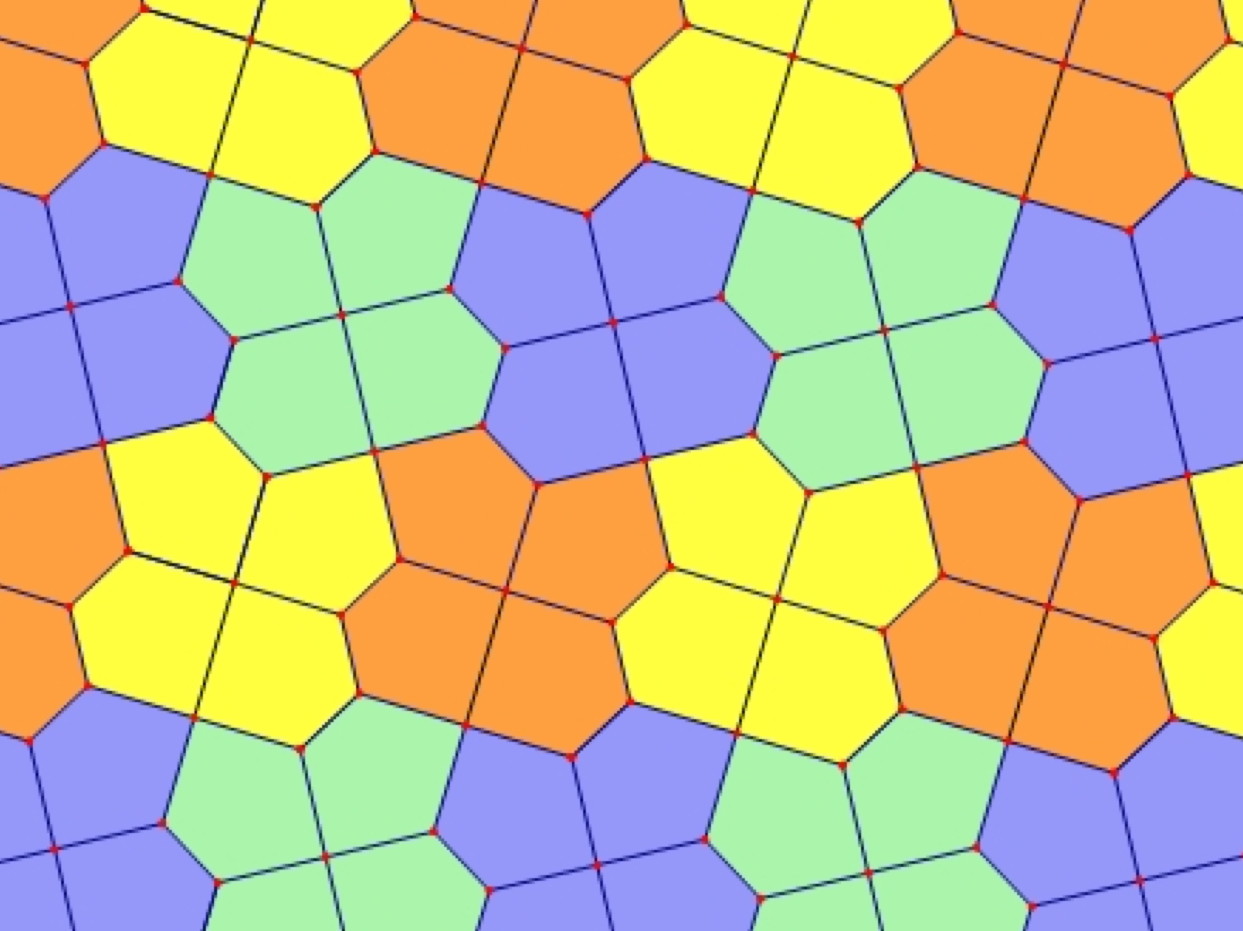

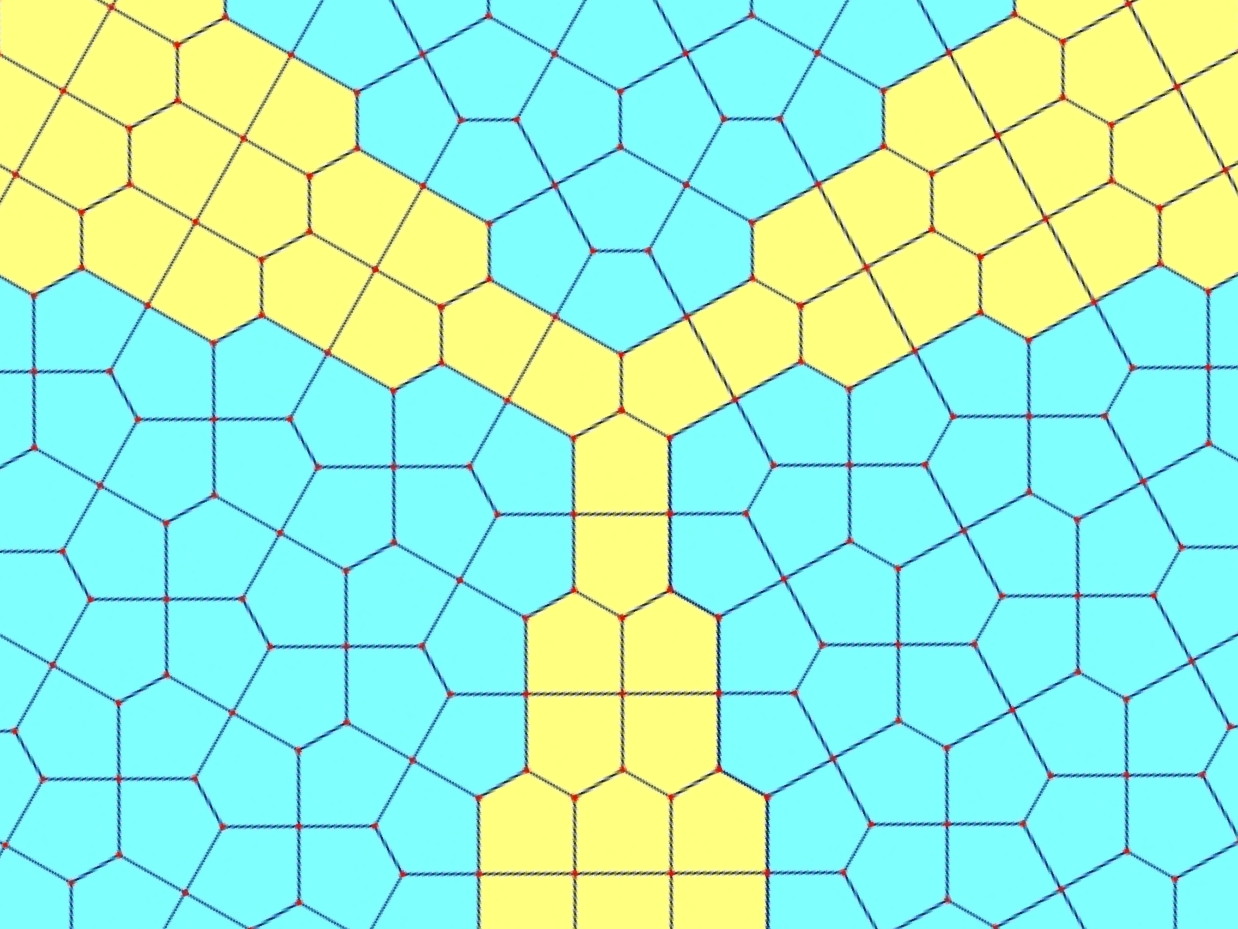

One of the infinitely many possible Cairo-Prismatic tessellations in which the Cairo tiles are in hexagonal groups of four and the Prismatic tiles are in pairs.

Another of the infinitely many possible Cairo-Prismatic tessellations in which the Cairo tiles are in hexagonal groups of four and the Prismatic tiles are in pairs.

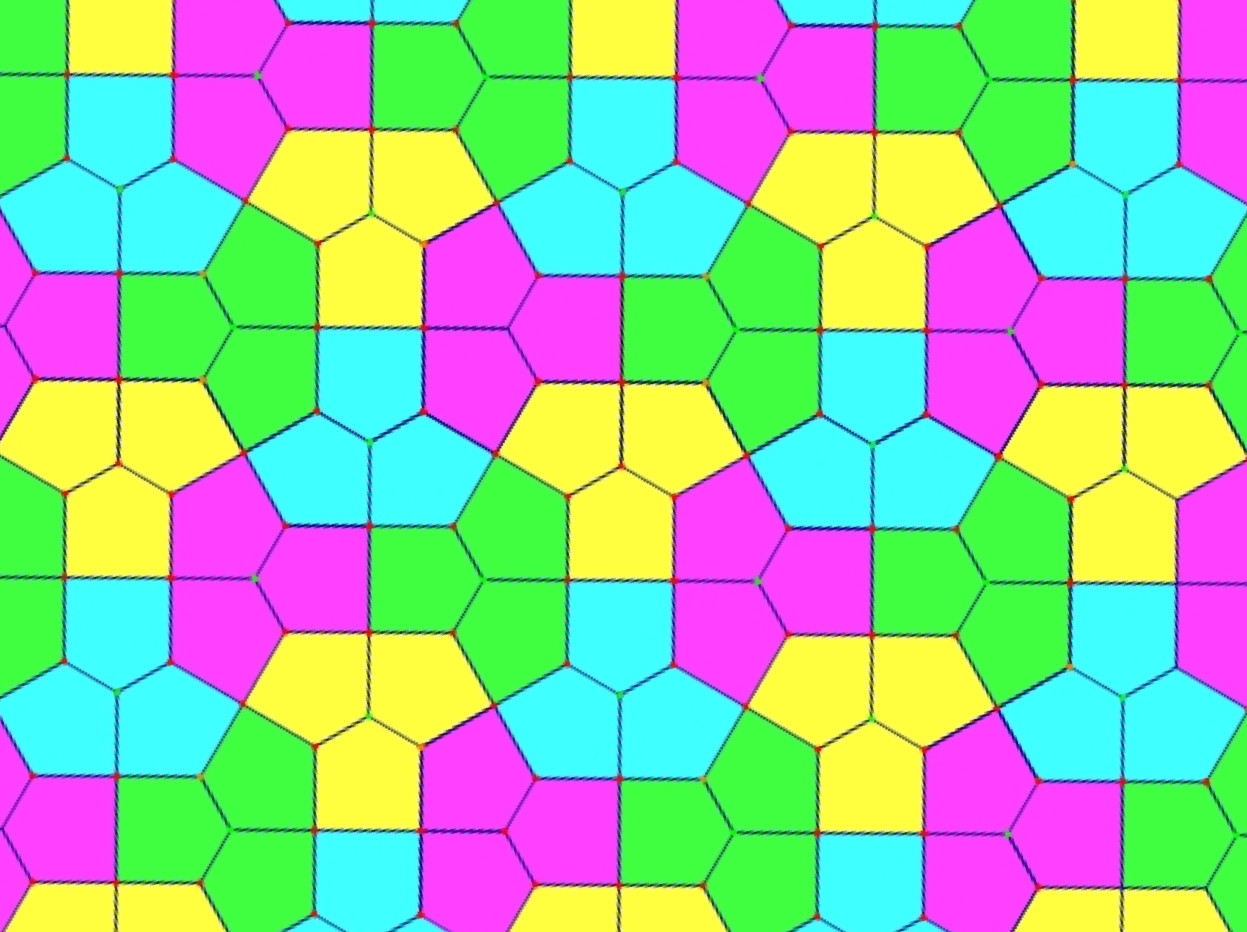

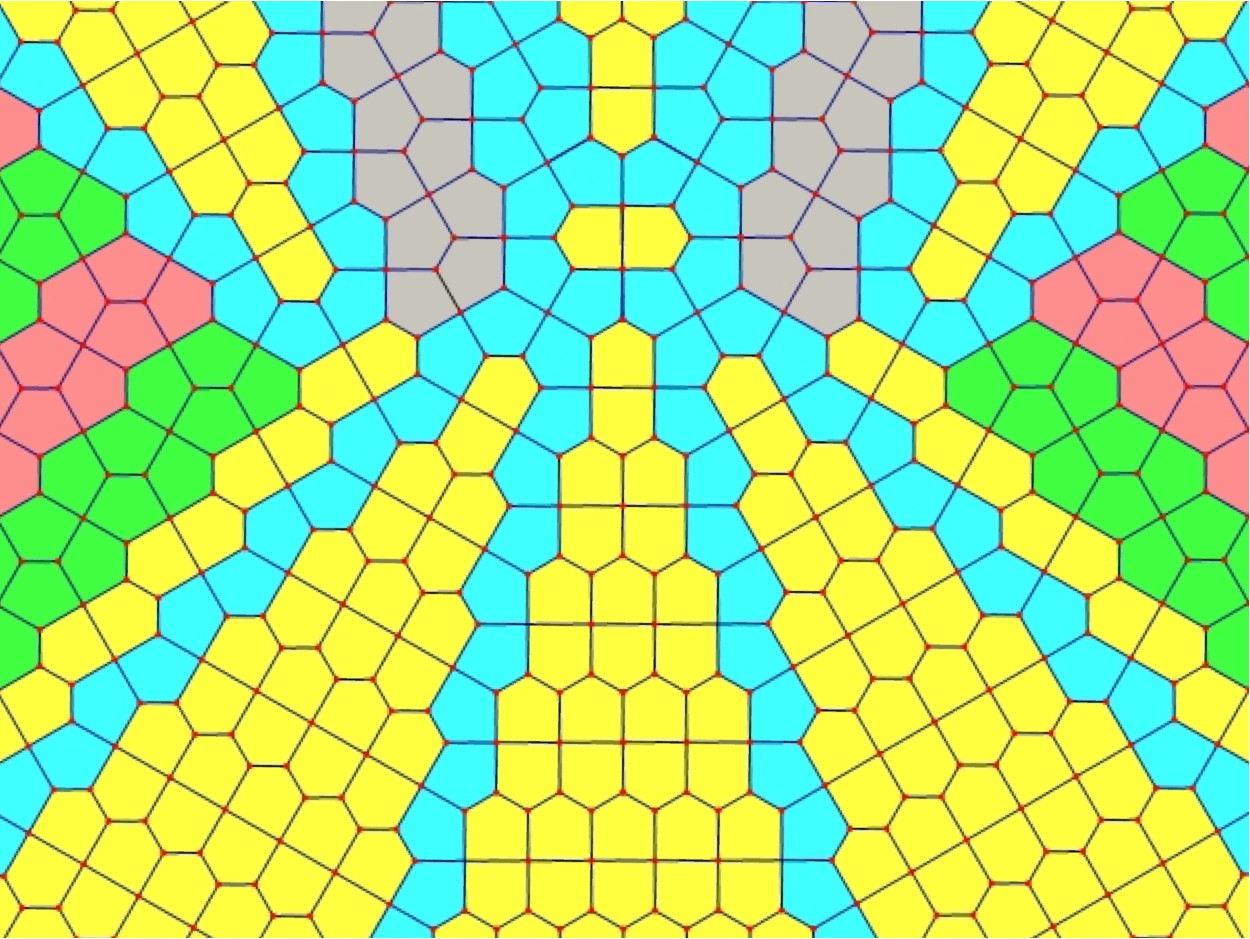

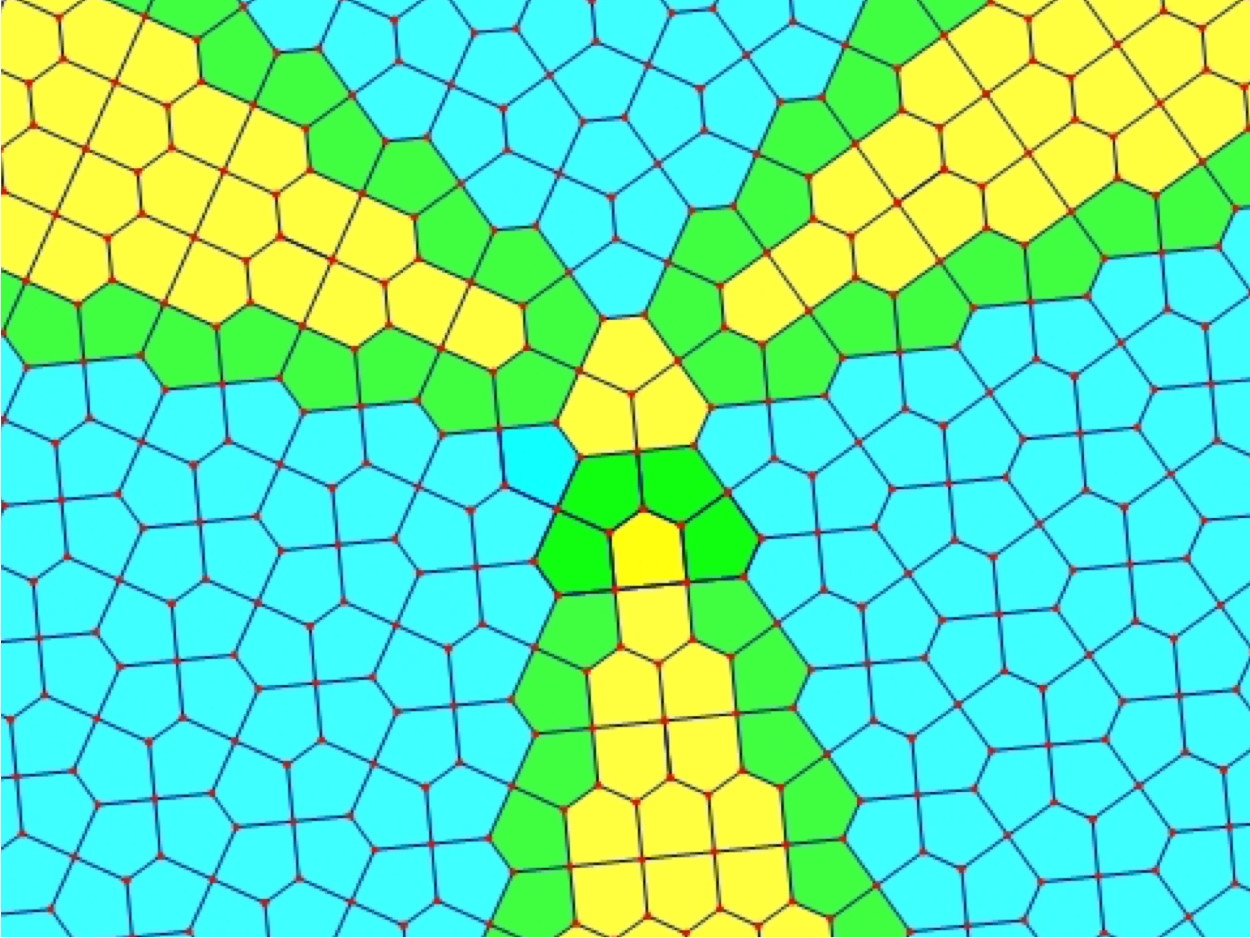

One of the Cairo-Prismatic tessellations found by amateur mathematician Marjorie Rice.

The “Sardines” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Sardines” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Pills” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Spaceship” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Christmas Tree” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Bunny” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Plaza” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Waterwheel” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Windmill” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Chaos” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Chung, Fernandez, Li, Mara, Rosa Plata, Shah, Sordo Viera, and Wikner, students of Frank Morgan.

The “Double Pillbox” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Maggie Miller, student of Frank Morgan.

The “River” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Maggie Miller, student of Frank Morgan.

The “Teeth” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Maggie Miller, student of Frank Morgan.

The “Yellow Brick Road” Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Maggie Miller, student of Frank Morgan.

A Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Victor Lu, student of Colin Adams.

A Cairo-Prismatic tiling found by Lilliana Morris and Byron Perpetua, students of Colin Adams.

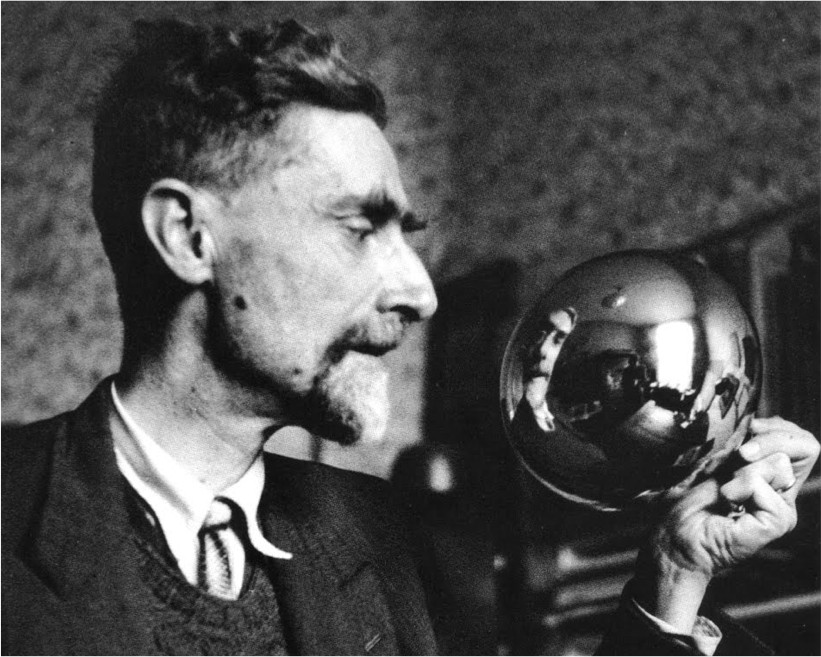

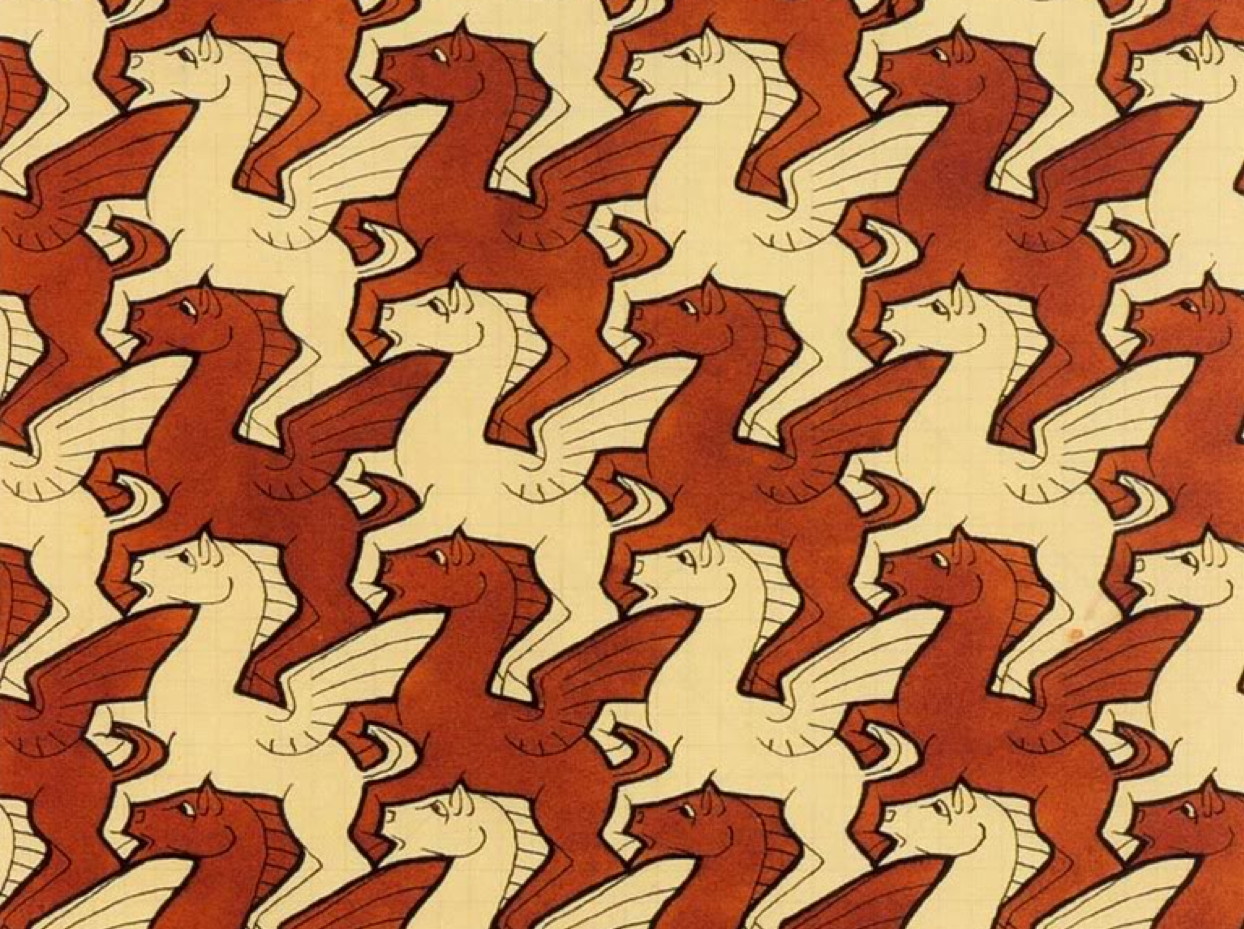

In his lifetime, the Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher produced over 150 tessellations. Birds, reptiles, fish, insects, and other strange creatures populate these wonderful colored drawings.

Escher used these tessellations in many of his prints and also in commissioned work that used Delft tile, cast concrete, wood inlay, and painting on walls or fabric. Escher had no higher education in mathematics and worked out his own rules for creating tiles that were sure to fit together. Escher’s tessellations have delighted many generations of admirers, and are used widely to teach about transformation geometry and the motions of translation, rotation, reflection, and glide-reflection.

Frank Morgan is the Webster Atwell ’21 Professor of Mathematics at Williams College. He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1977. In his research he studies minimal surfaces and the behavior and structure of minimizers in various dimensions and settings, and he is well known for his part in proving the Double Bubble Conjecture in 2002. He has worked with dozens of students in the SMALL summer undergraduate research program at Williams College, most recently concerning tilings of the plane by Cairo and Prismatic pentagons.

Morgan has authored six books: Geometric Measure Theory: a Beginner’s Guide, Calculus Lite, Riemannian Geometry: a Beginner’s Guide, The Math Chat Book, Real Analysis, and Real Analysis and Applications. He has received numerous awards for distinguished teaching, and from 2000-2002 he served as Second Vice President of the Mathematical Association of America.

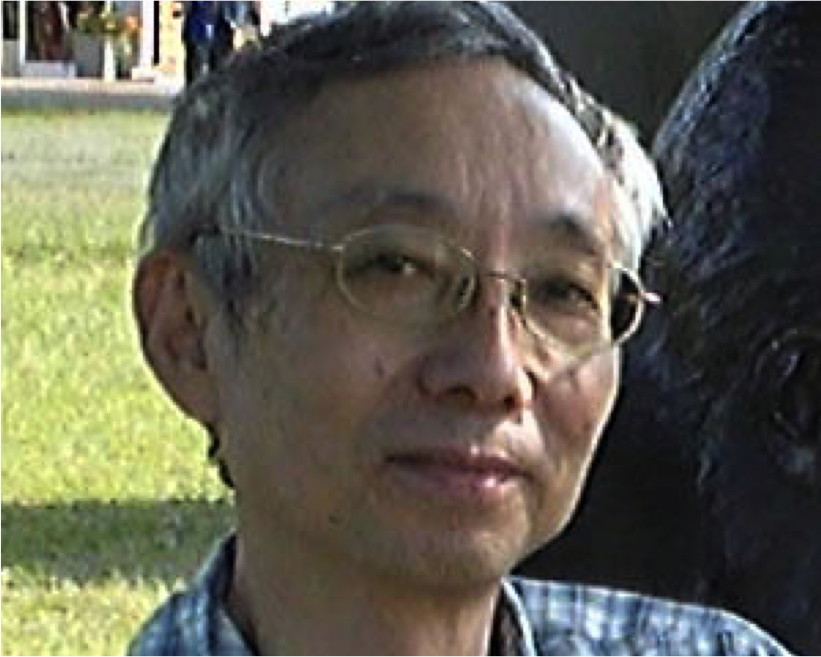

Makoto Nakamura, Tokyo artist, is a graduate of Tama Art University and founder of the Japan Tessellation Design Association (JTSA). Inspired by Escher’s work, Nakamura has made dozens of wonderful tessellations using animal shapes, including the monkey, rabbit, and dinosaur tiles at Tessellation Station. And, like Escher, he has used his tessellations to create other fanciful worlds in prints and drawings, as well as jigsaw puzzles, layered three-dimensional renditions, and sculpted tessellations on spheres. In his prints, his interlocked creatures metamorphose and break free from their locked positions. On his web site, you can find a large catalog of his tessellations, live animations of his creatures metamorphosing, as well as animated puzzle games.

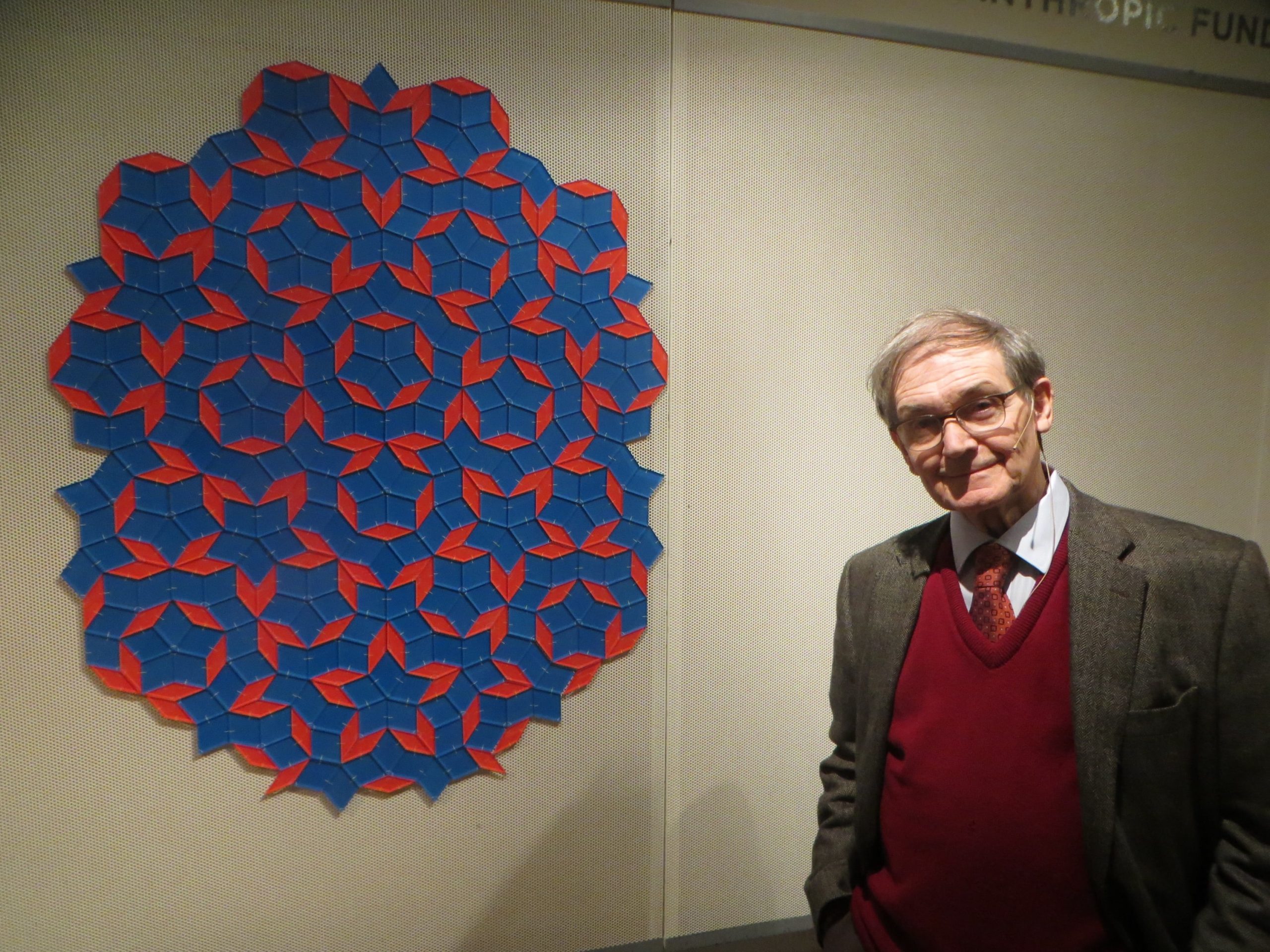

Roger Penrose is a British mathematical physicist who has made great contributions to our understanding of the cosmos. He has long been interested in tilings, and in particular, those for which no translation (sliding) can superimpose the tiling so all tiles match exactly. These are known as aperiodic tilings, and Penrose was the first to discover pairs of tiles that, when given rules for matching edges of tiles, produced only aperiodic tilings. The pair of rhombuses here (and seen in the picture of Penrose) are one such aperiodic set, and another famous pair is a kite and dart, related to the pair of rhombuses. These tilings now are called Penrose tilings, and all exhibit local 5-fold rotational symmetry.

Marjorie Rice had no mathematics courses beyond general math in high school; she studied to be a secretary. Yet her curiosity and love of mathematical puzzles led her to investigate a problem that she read about in a 1975 Scientific American column by Martin Gardner. She wanted to find pentagons that could tile the plane that had not been previously discovered. Over a two-year period, she found four new types of pentagonal tilings, working out her own notation and method of inquiry. She also found hundreds of different tilings by combinations of pentagons, and drew them by hand. From some of these, she created tessellations of flowers, butterflies, bees, fish, and shells.

Dr. Doris Schattschneider received her Ph.D. from Yale University in 1966. She is recognized internationally as an expert in tessellations of the plane and the work of M.C. Escher. After a career as a member of the math faculty at Moravian College, Dr. Schattschneider is now Professor Emerita of Mathematics. She has authored and co-authored numerous books and articles, including M.C. Escher Kaleidocycles, Visions of Symmtery, and A Companion to Calculus. Professor Schattschneider advised on the choice of tiles to create tessellations in Tessellation Station.

The Tali and Boaz Weinstein Philanthropic Fund provided support that made Tessellation Station possible.

Marc Engel of Alexander Scott Graphics provided dinosaur and rabbit tiles at reduced cost for use with Tessellation Station.

A simple tiling of paper by parallelograms, if folded along the edges just right, results in an origami pattern known as a Miura fold.

As you can see in the moving image, a paper folded in this way can move smoothly from a very small folded position into a large, flat unfolded position. NASA uses this type of folding in some of their solar sails.

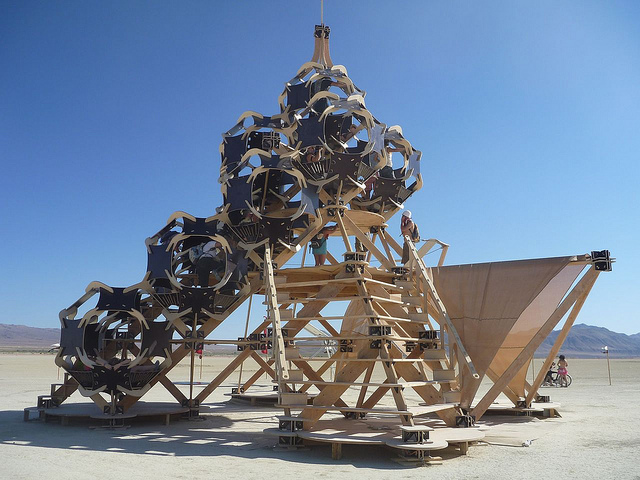

This is the Otic Oasis, a community-built shelter designed by architect Gregg Fleishman. It was constructed at the 2012 Burning Man Festival by a team of volunteers.

At Tessellation Station our goal is to fill two-dimensional space on a wall with combinations of polygon tiles. In the same way, Fleishman’s goal was to build a structure that fills three-dimensional space with a combination of polyhedra.

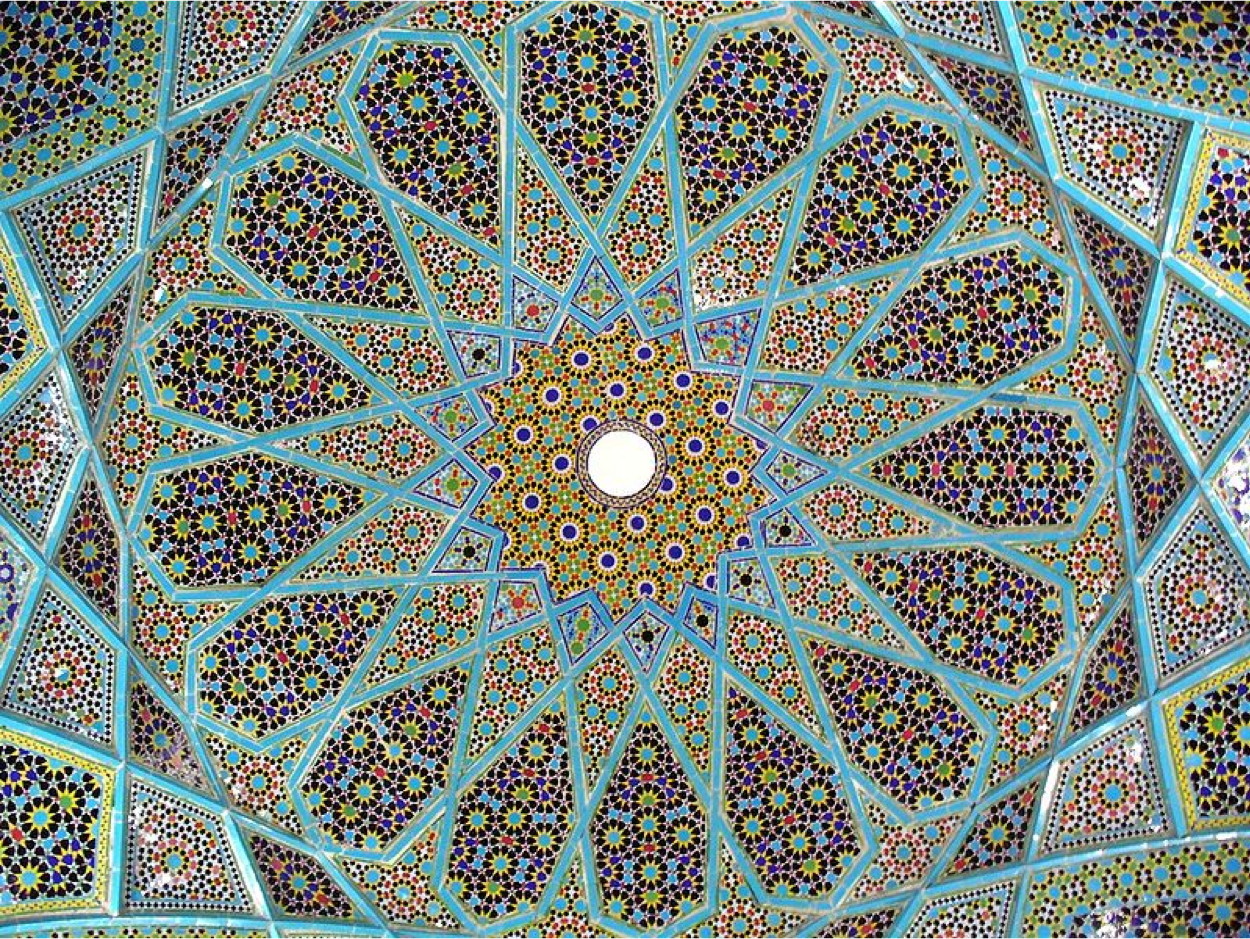

This the the ceiling of the Tomb of Hafez in Iran. This type of decoration is called a girih pattern.

The design of this sophisticated mosaic is made using strapwork lines that are placed across a pattern made up of stars and polygons. Although such girih designs have been used for 500 years in Islamic art, they have only recently begun to be studied by mathematicians.

Graphic artist M.C. Escher was famous for creating mathematical art like the Pegasus tiling shown here. His work can be found all over the world and in nearly every poster store!

The tiles used in this piece of art are based on a simple square tiling, in the same way that the monkeys, rabbits, and dinosaurs at Tessellation Station are based on simple polygon tilings.

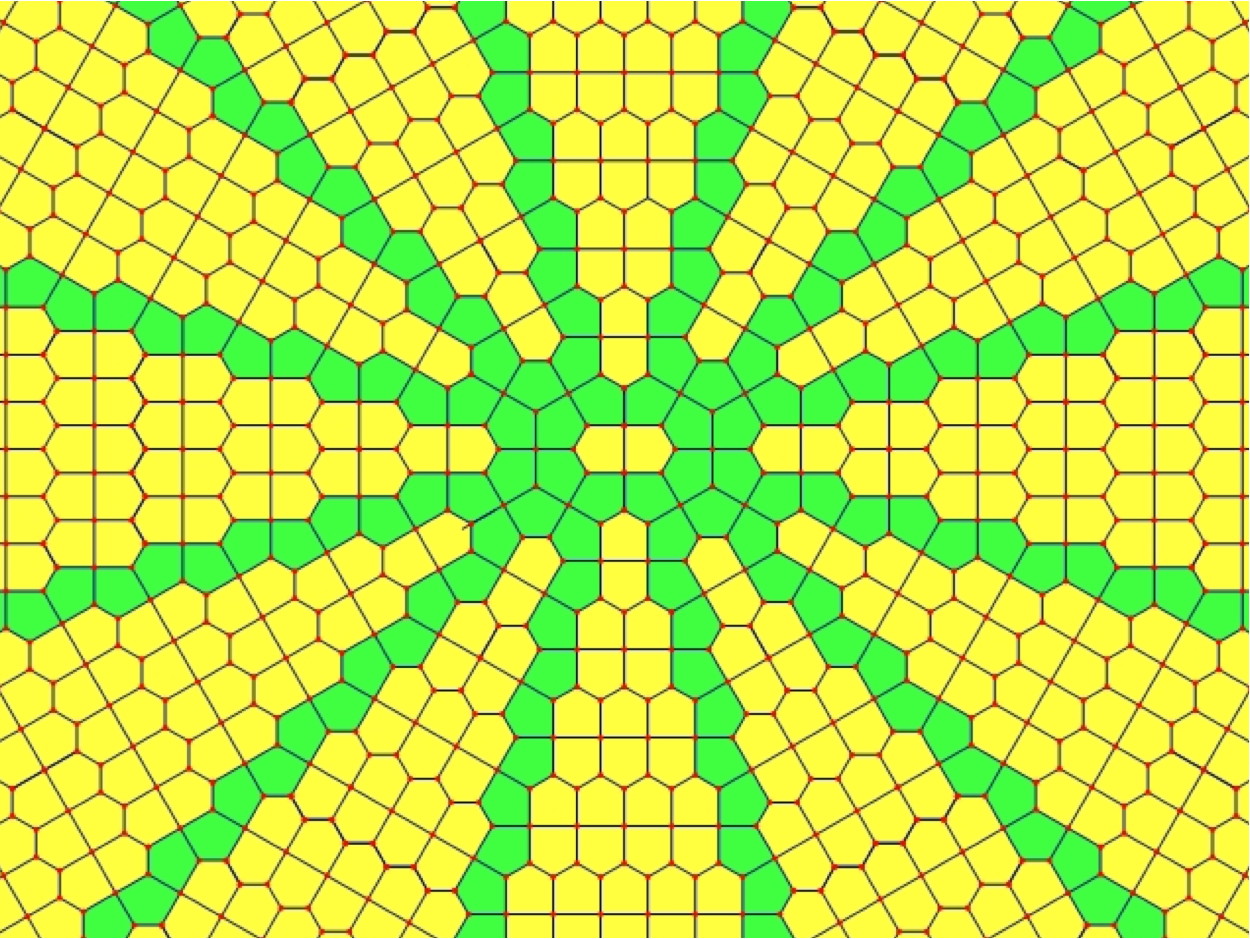

The tiles shown here are irregular pentagons discovered by Marjorie Rice, who discovered four types of new tilings in 1977. Rice had no mathematical education past high school, but discovered four of the 14 known pentagonal tilings.

To honor Rice, the Mathematical Association of America used one of her tilings on the floor of the entrance of their headquarters in Washington, DC.

Granko Grunbaum and G.C. Shephard

This book is the ultimate reference on definitions, results, history, problems, and much more about tilings. It has an extensive chapter on tilings by regular polygons, and another on Penrose tilings.

Eugenie Hunsicker and Laura Taalman

This article from Math Horizons describes the work of Los Angeles artist and architect Gregg Fleishman, who uses three-dimensional tessellating polyhedra in his modular constructions.

Peter Lu and Paul Steinhardt

This paper in Science argues that the girih patterns used in Islamic architecture in the 15th century combined tessellations and self-similar transformations to create quasi-crystalline Penrose patterns that predated the discovery of such patterns in the West by 500 years.

Makoto Nakamura

This web site is filled with the tessellations and other work of Tokyo-based artist Makoto Nakamura. The monkey, rabbit, and dinosaur tessellating tiles are there as well as dozens of other animal tessellations, animations of polygon tiles metamorphosing into animal tiles, images of Nakamura’s three-dimensional work, photographs of carved balls with tessellations, and more.

Yutaka Nishiyama

This 2012 article discusses how an origami technique called Miura folding based on tessellating crease patterns can be used to create folding maps and solar panels for use in space. Miura folds follow a tessellation of non-right-angle parallellograms and result in paper or other materials that can be folded or unfolded with one fluid motion.

Doris Schattschneider, Moravian College

This article from The Mathematical Gardner in 1981 tells the story of how

Marjorie Rice discovered four new types of convex pentagons that can tile the plane.

Doris Schattschneider, Moravian College

This book contains color reproductions of all of Escher’s tessellations, and tells the story of how he made them.

Doris Schattschneider, Moravian College

This 1978 article from Mathematics Magazine discusses classes of convex pentagons and convex equilateral pentagons that can tile the plane. Although there have been claims that the list of 14 classes of tiling pentagons is complete, there is no proof, and the problem is still open.

Pedagoguery Software

With the Tess software, you can quickly create attractive symmetric planar illustrations. While you draw, Tess will automatically maintain the symmetry group you have chosen; 24 rosette, all seven frieze, and all 17 wallpaper groups are included.