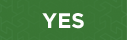

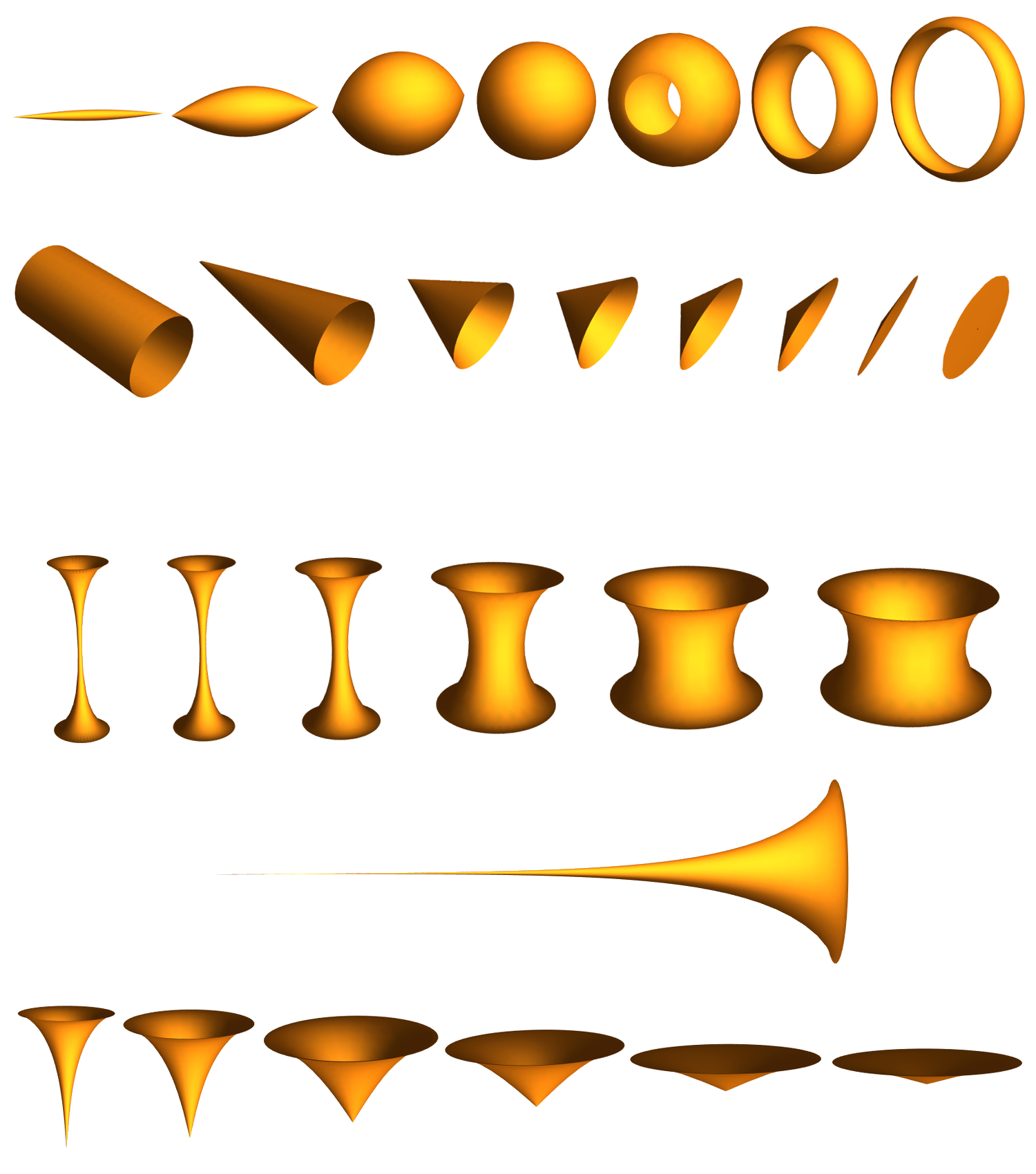

Shapes of Space explores the differences among three types of surfaces. Try putting the foam patches on the different surfaces. You might find that a patch that fits snugly on a cylinder falls off of the sphere and does not fit at all on the third, saddle-like shape, no matter where you try to place it on these surfaces. What makes these surfaces so different?

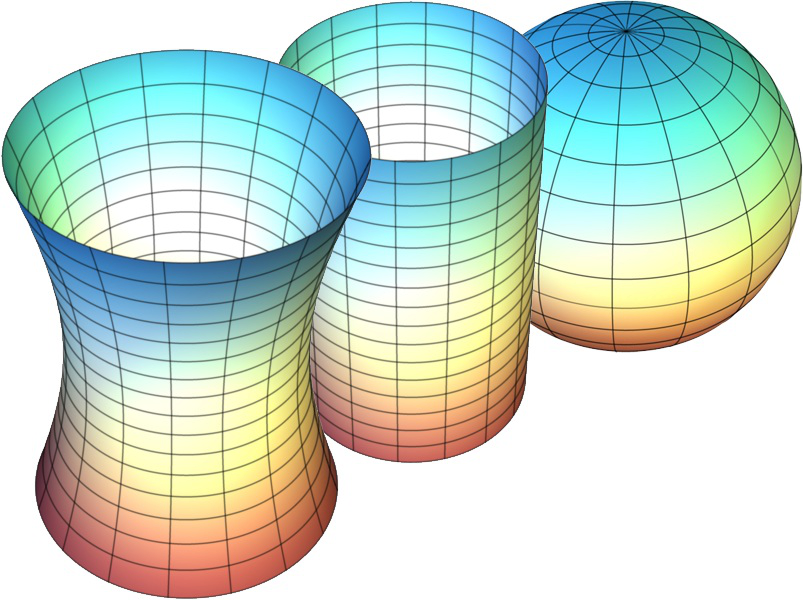

The difference among the three surfaces is how they curve. All three look a little curvy, of course, but we can see differences in the way they curve. Think about cutting a small patch out of the sphere. If you did so, you would find that the patch you cut out would not lie flat unless you ripped or stretched it, instead keeping its dome-like structure. With the cylinder, you could unroll the small patch like a scroll so that it lies flat. With the pseudocylinder, if you cut out a small patch, you would find that it keeps its saddle shape. Mathematicians classify these types of curvature as positive, zero, and negative.

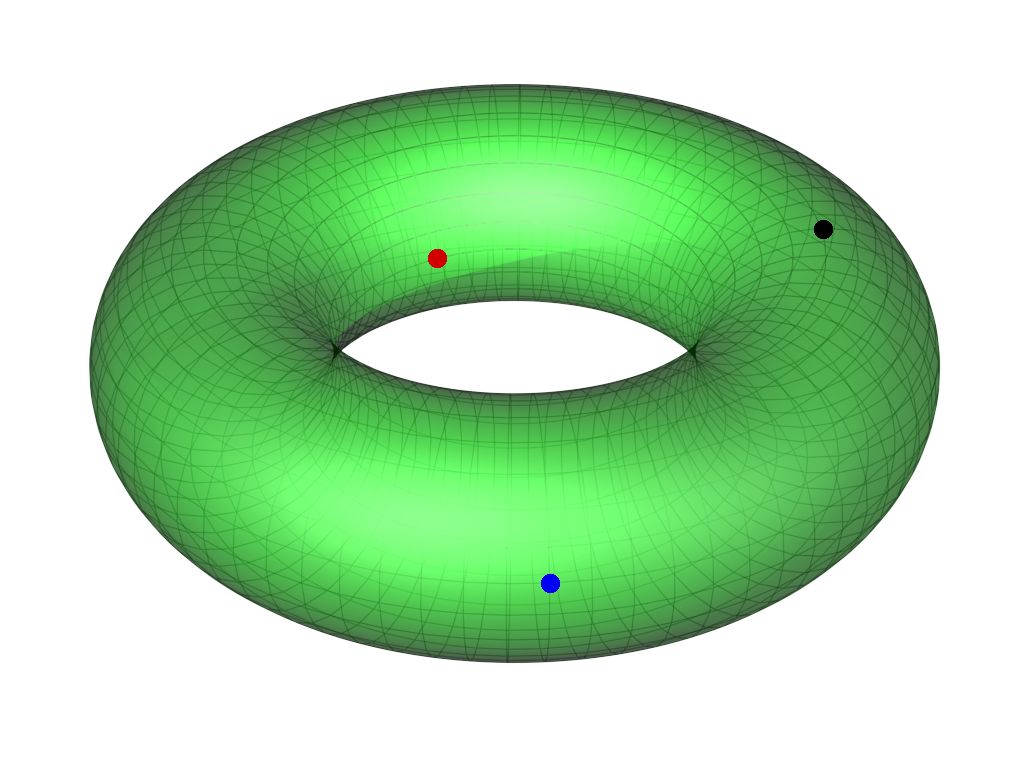

Every surface in space consists of these types of points, and many surfaces have all three types. If you look at the torus (doughnut) to the right, you’ll find that the blue point has positive curvature, the black point has zero curvature, and the red point has negative curvature. (See if you can spot the dome, scroll, and saddle.)

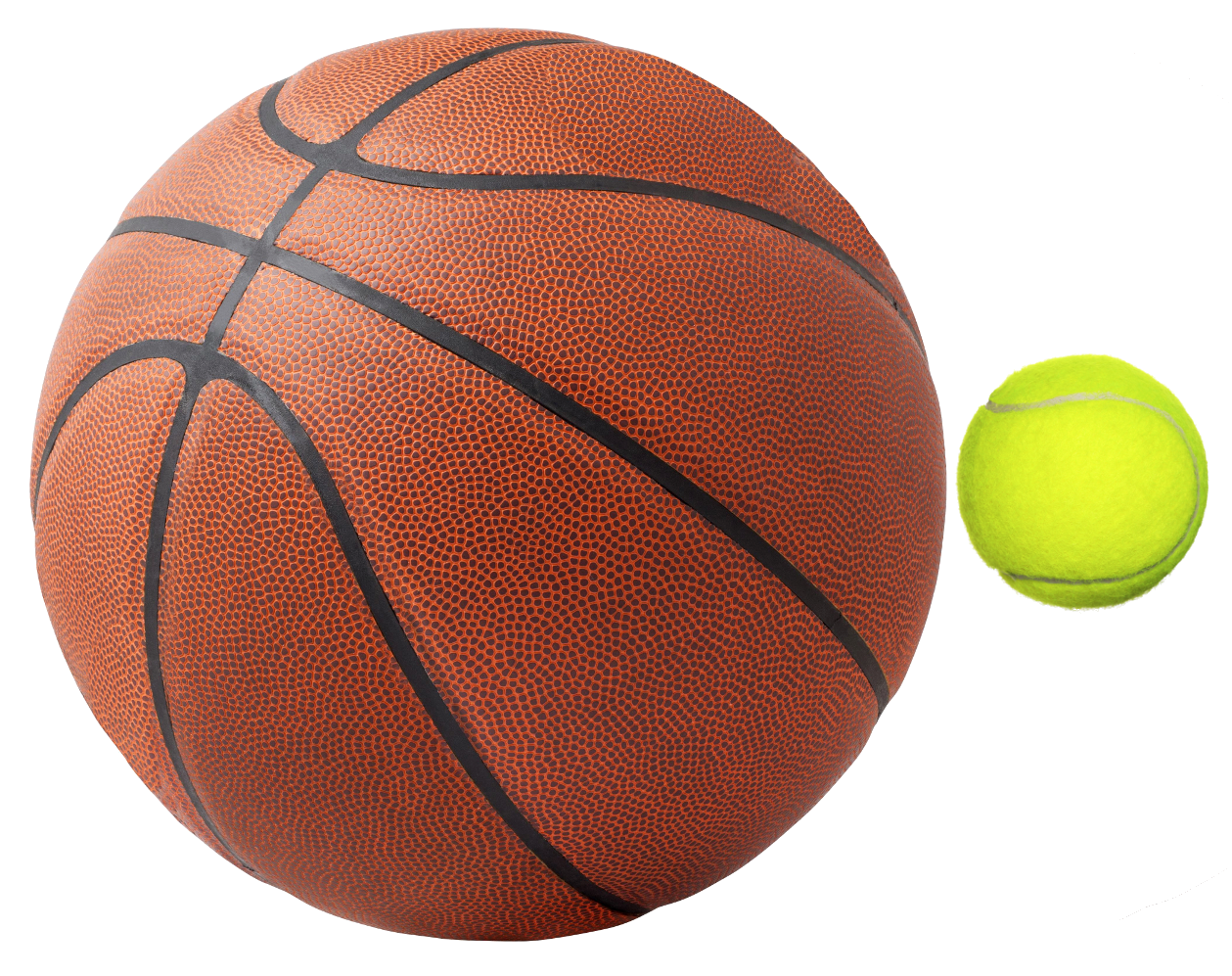

When mathematicians talk about curvature of a surface, they are usually talking about a quantity called Gaussian curvature. For every point on a surface, we can assign a number that tells how much the surface curves at that point. Positive numbers would indicate that the surface looks sort of like a dome at that point, but the larger the number, the more extreme the doming. If you picture an ant standing on a basketball, the surface is pretty convincingly flat, since as the ant walks along it, it gently curves away. On the other hand, if an ant walks along a tennis ball, the surface falls away more sharply and it is more apparent to the ant that she is standing on a dome-like patch.

It turns out that the Gaussian curvature at a point on the sphere is , where is the radius of the sphere. This means that as the radius gets bigger, the curvature is lower. We intuited this mathematical fact when we thought about our ant, because she saw the larger basketball as much flatter than the smaller tennis ball. The Earth has a very big radius, and it certainly fooled humans into thinking it was flat for thousands of years!

In some sense, a point of positive curvature has “too little” area around it, which forces the structure to start bowling up. On the other hand, a point of negative curvature has “too much” area around it, which warps the structure in a different way.

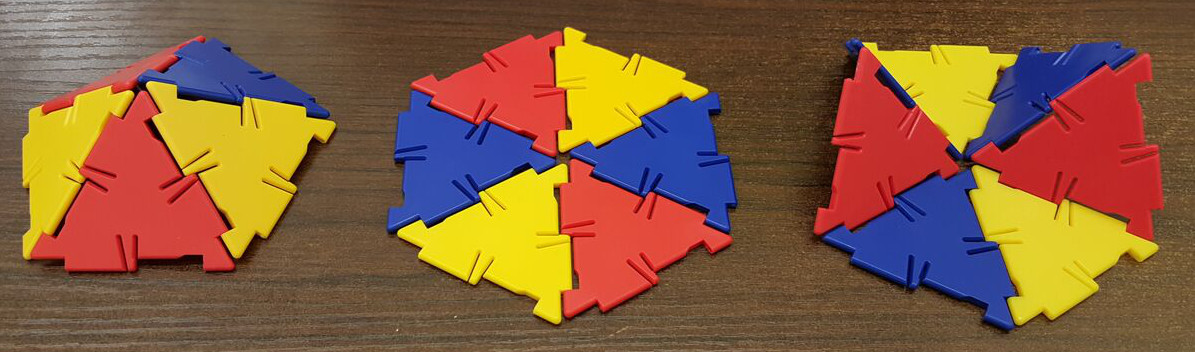

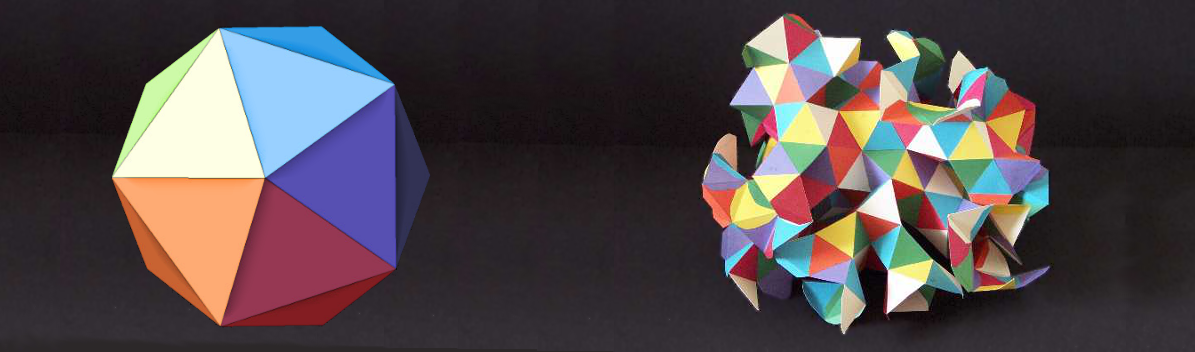

It’s easy to see this effect if we approximate with triangles. Pictured to the right, we have points surrounded by 5, 6, and 7 triangles. Since an equilateral triangle’s angles are all 60°, six triangles are required to get the familar 360° around a point. If we have three, four, or five triangles around a point, the structure begins to bowl, and we could continue the pattern to get a tetrahedral, octahedral, or icosahedral approximation of a sphere. If we have seven or more triangles around a point, a saddle forms, and some pretty wild things can happen if you try to continue the pattern! (You can experiment with these and other forms over at the Structure Studio.)

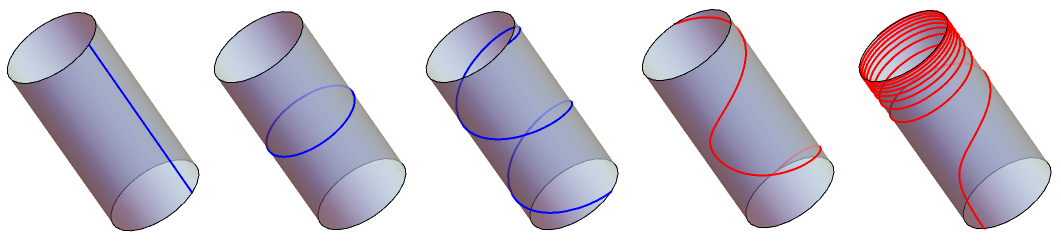

Suppose you were to pick two points A and B on one of these surfaces. If an ant were standing on A, what is the shortest path he could take to get to B? In a plane, the shortest path is always along a straight line, but what about on one of our curved surfaces? Since unrolling the cylinder into a sheet doesn’t change the distances, the shortest paths on a cylinder must unroll into lines. Such paths look like lines down its length, circles around its circumference, and evenly-spaced corkscrews. On the sphere, these paths of shortest distance are all along equators, otherwise known as great circles.

These curves are called geodesics and are the closest thing to “straight lines” on surfaces. To the right, some geodesics on the cylinder and sphere are traced in blue while some nongeodesics are traced in red. Can you see how the blue paths head “straight” within the surface while the red paths seem to turn away?

In the plane, there is exactly one geodesic connecting A and B, and it always gives you the shortest path. On other surfaces, however, there might be long geodesic paths from A to B in addition to the shortest one. Can you find two points on the cylinder that you can move between via both a corkscrew and a line?

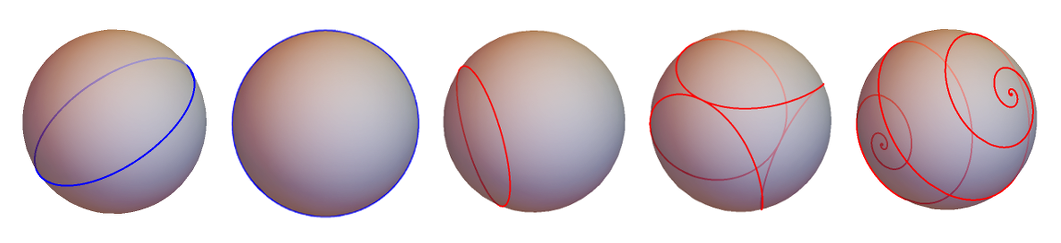

On a flat surface, we make polygons like triangles and squares by picking a points and connecting them with straight line segments. It works pretty much the same way on a curved surface, except instead of following a line between two points, we follow a geodesic arc. To the right, you can see three different geodesics drawn on each of our surfaces. Highlighted in yellow is a triangle whose sides are given by these arcs.

If you look at the cylinder, it might be a little hard to tell, but the sum of the triangle’s interior angles is 180°, just like in planar geometry. On the other hand, it turns out that any triangle drawn on the sphere will have an interior angle sum greater than 180°. (For small triangles, it will be pretty close to 180°. If you choose as your points the north pole, a point on the equator, and another point on the equator 1/4 of the way around the sphere, then this triangle’s angles will each be 90°, giving 270° total!) The sum of the angles in a triangle on the pseudocylinder will always be less than 180°.

An interesting property that each of these surfaces has is that it has the exact same Gaussian curvature at every point. We say these are surfaces of constant curvature. It might be obvious that the curvature is the same at every point on the sphere because we can rotate the sphere to take each point to any other. The cylinder is similarly highly symmetric. That the pseudoclinder has constant curvature is perhaps a little more surprising. Surfaces of constant curvature provide us with nice models for doing Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry. For example, if you take the pseudocylinder and think of its geodesics as “lines,” you end up with a nice way to visualize hyperbolic geometry.

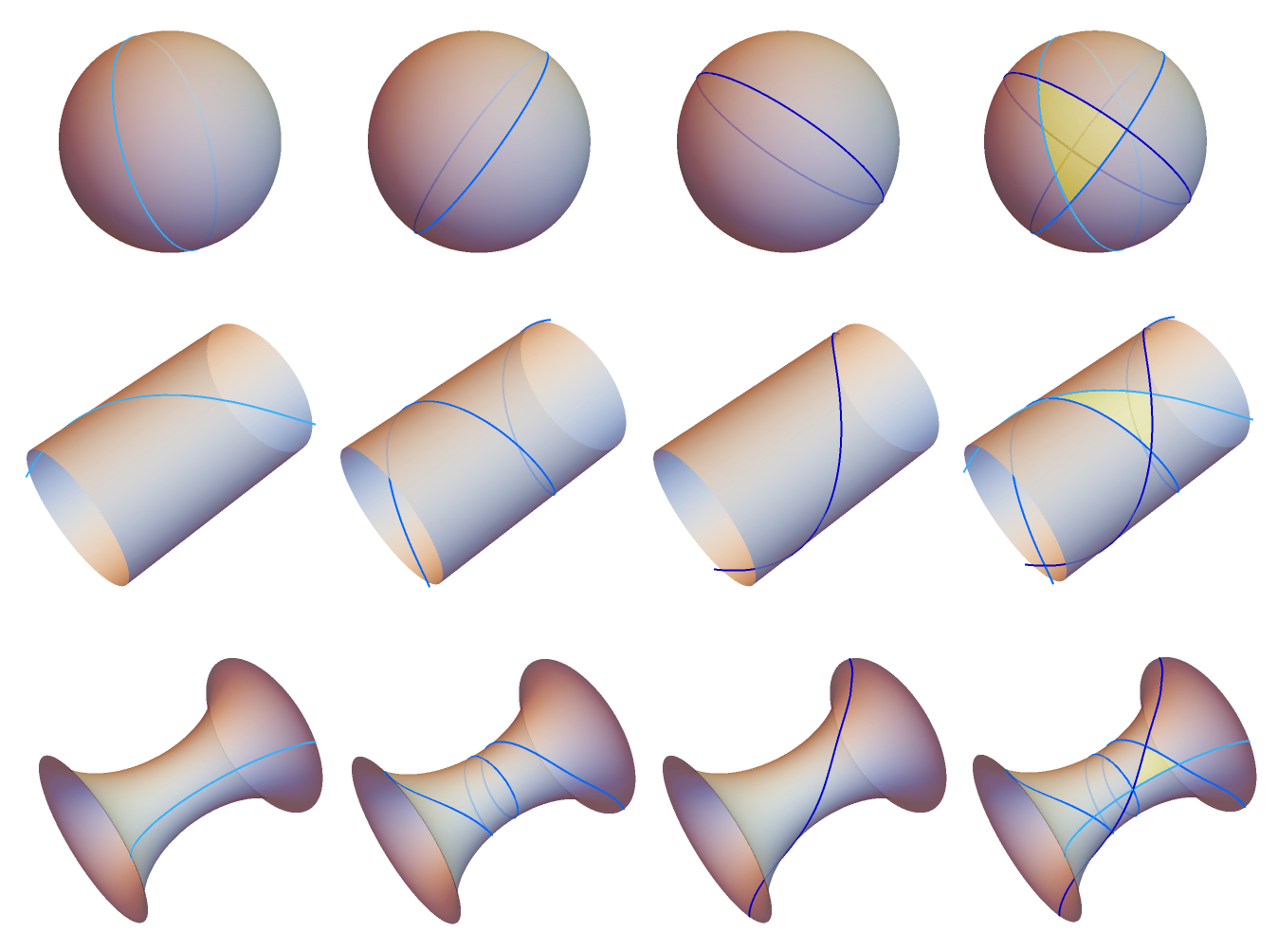

What other surfaces of constant curvature are there? You might be surprised to find that there are other surfaces besides the sphere with constant positive curvature. If we only consider the ones that are surfaces of revolution, then there is an entire family, morphing from football-like shapes to bands. The sphere is precisely the one with neither holes nor cusps. The cylinder is at the end of a family of cones, which all have constant zero curvature, the other end being the plane. It turns out there are three families of with constant negative curvature. (The middle surface, commonly called the pseudosphere, is in a class by itself!)

The classic soccer ball design, here rendered by Aaron Rotenberg, has one black pentagon meeting two white hexagons at every vertex. To tile the plane, the black tiles would also have to be hexagons. In hyperbolic space, the black tiles could be heptagons, as in the model by Frank Sottile.

The iconic soccer ball design is based on a truncated icosahedron. These quilted balls are based on the dodecahedron and icosahedron. How else could a soccer ball be designed?

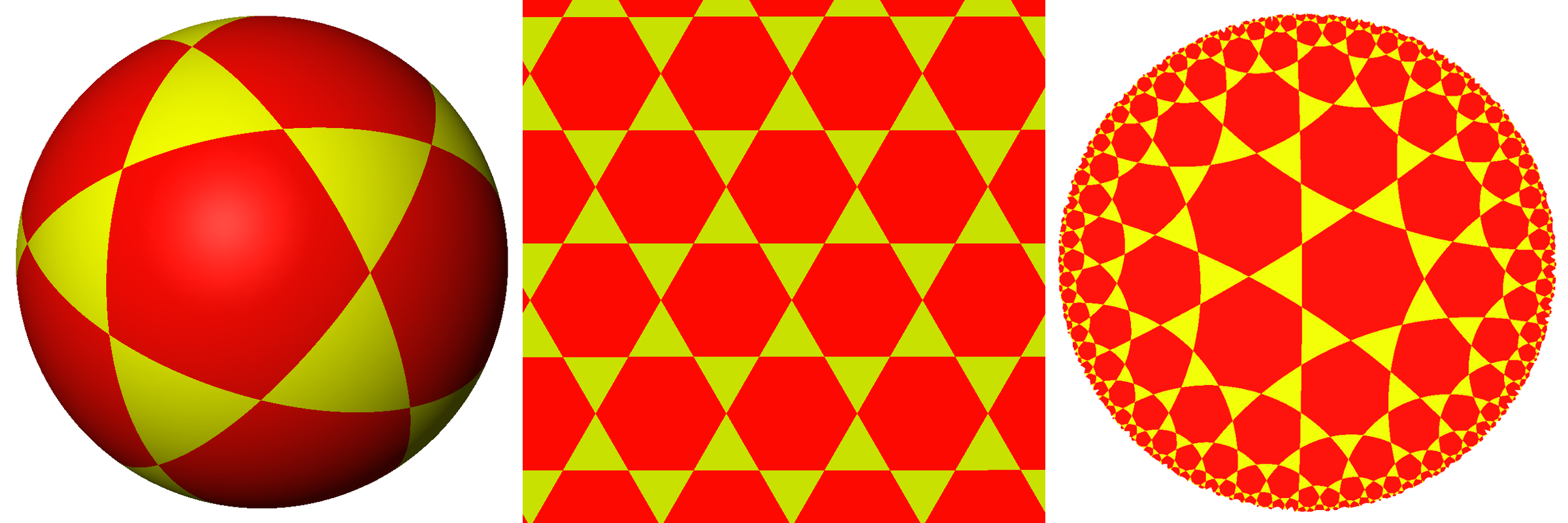

Here is a family of related spherical, planar, and hyperbolic tilings. The hyperbolic tiling was made using the Poincare disk model of hyperbolic space.

Fitting together shapes on differently curved surfaces would have been a cinch for Russian mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya (1850 – 1891). She became renowned for her work on analysis, partial differential equations, and mechanics, and served as editor of the prestigious journal Acta Mathematica.

Support from David De Weese helped make Shapes of Space possible.

Euclid recorded five postulates in his book The Elements in 300 BC, which laid the foundations of geometry. He accepted these five facts as unquestionable truths and then tried to derive the rest of geometry from them:

(1) A straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points.

(2) Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line.

(3) Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center.

(4) All right angles are congruent.

(5) If two lines are drawn which intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough.

While the first four were relatively simple, the fifth seemed clunky. Euclid avoided using it to prove Propositions 1-28 in The Elements, but eventually could not find a way around using it. For centuries, mathematicians suspected it was a consequence of the other four postulates.

In 1823, János Bolyai and Nikolai Lobachevsky independently realized that there can be geometries in which the fifth postulate does not hold. In a letter to Bolyai’s father, Gauss mentions that he had discovered non-Euclidean geometry several years earlier, but he did not publish his findings. Gauss introduced the term non-Euclidean geometry, describing the geometry he, Bolyai and Lobachevsky had discovered. This geometry, today more commonly known as hyperbolic geometry, has constant negative (Gaussian) curvature, while Euclidean geometry has constant zero curvature. Later, Klein introduced the term elliptic geometry, to describe spaces with constant positive curvature. Today, non-Euclidean geometry most commonly refers to either hyperbolic or elliptic geometry.