Many animals travel in large groups: flocks of birds, swarms of bees, and schools of fish. Amazingly, each animal only needs to follow simple rules to know how to move with the group.

The robots in this exhibit are a similar type of group with which you can experiment to understand swarm behavior.

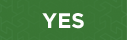

When in Pursue mode, the robots come after you. Each color group of robots is attracted to one of the people wearing a SensorPack in the exhibit.

Each robot will move toward its target person, trying to get as close as possible.

The robots also try to avoid bumping into each other.

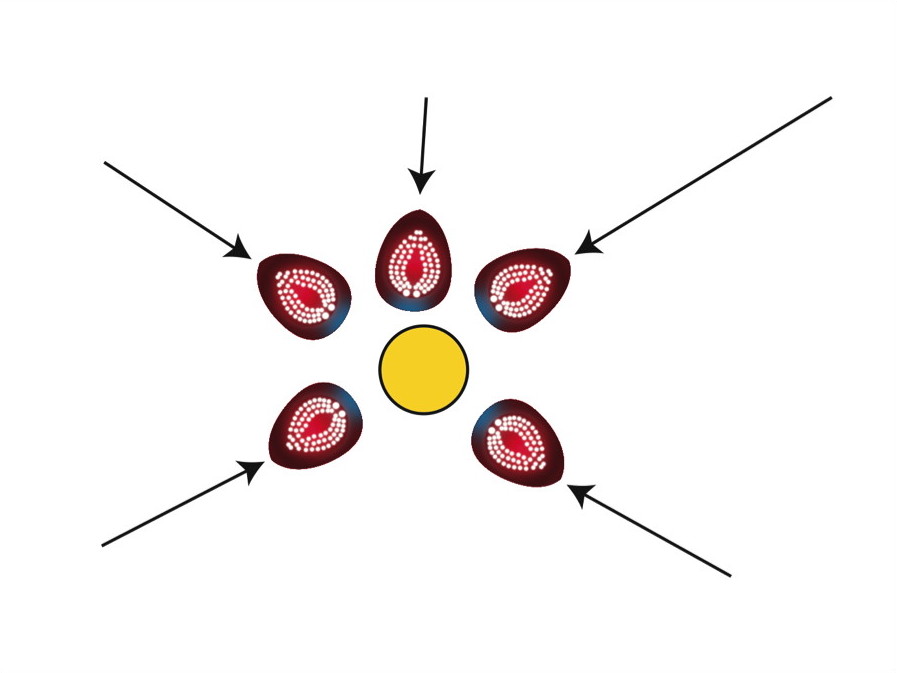

When in Run Away mode, the robots try to get away from you. All the players in the Robot Ring can scare their robots into the corners.

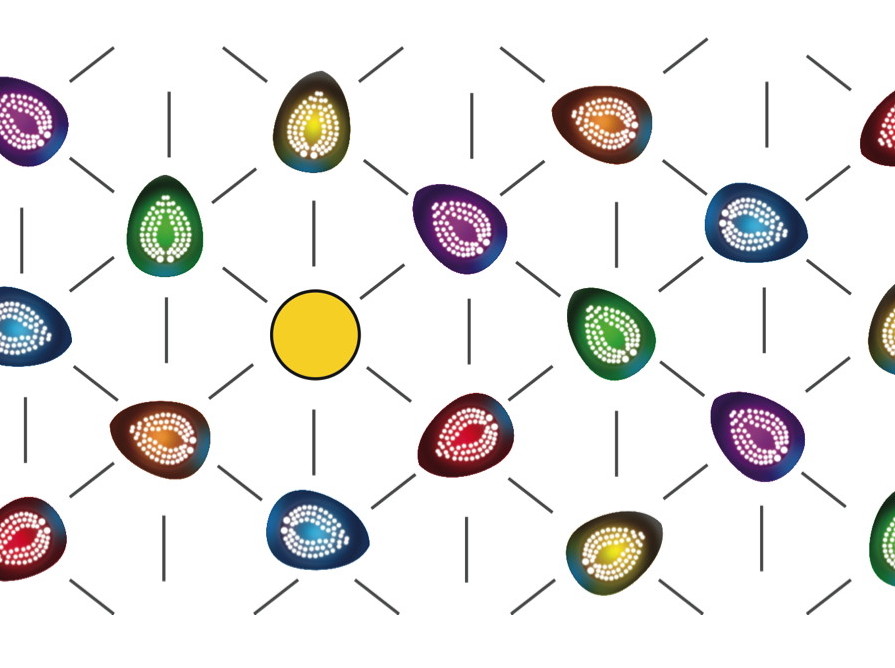

The robots can tell where people are in the Robot Ring, and they use that information to decide which directions to move.

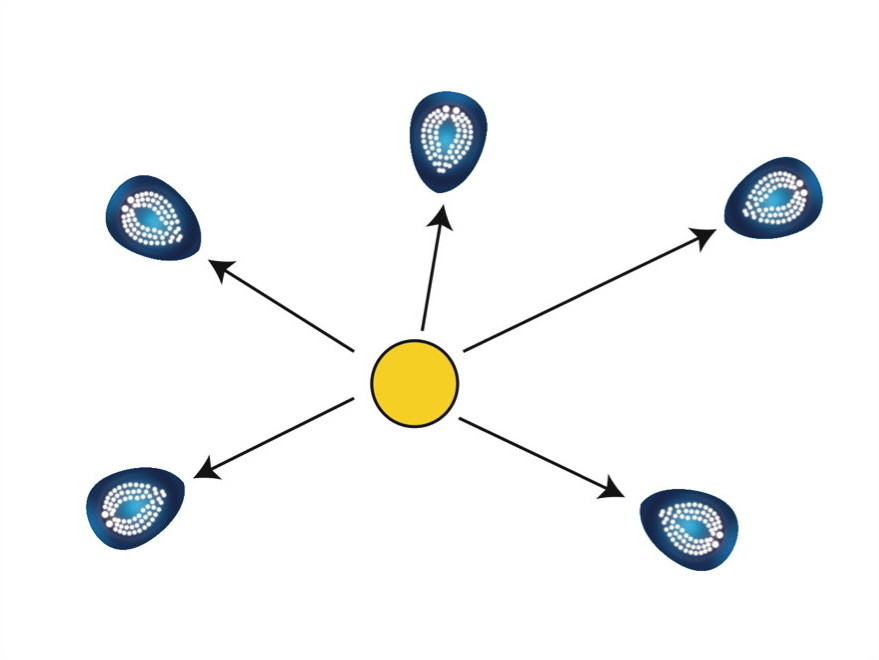

When in Swarm mode, the robots act like a school of fish, moving together as if they were one organism. How do they do that? By copying each other!

Each robot copies the movements of its nearest neighbors. Since each robot is doing this, they all end up moving together.

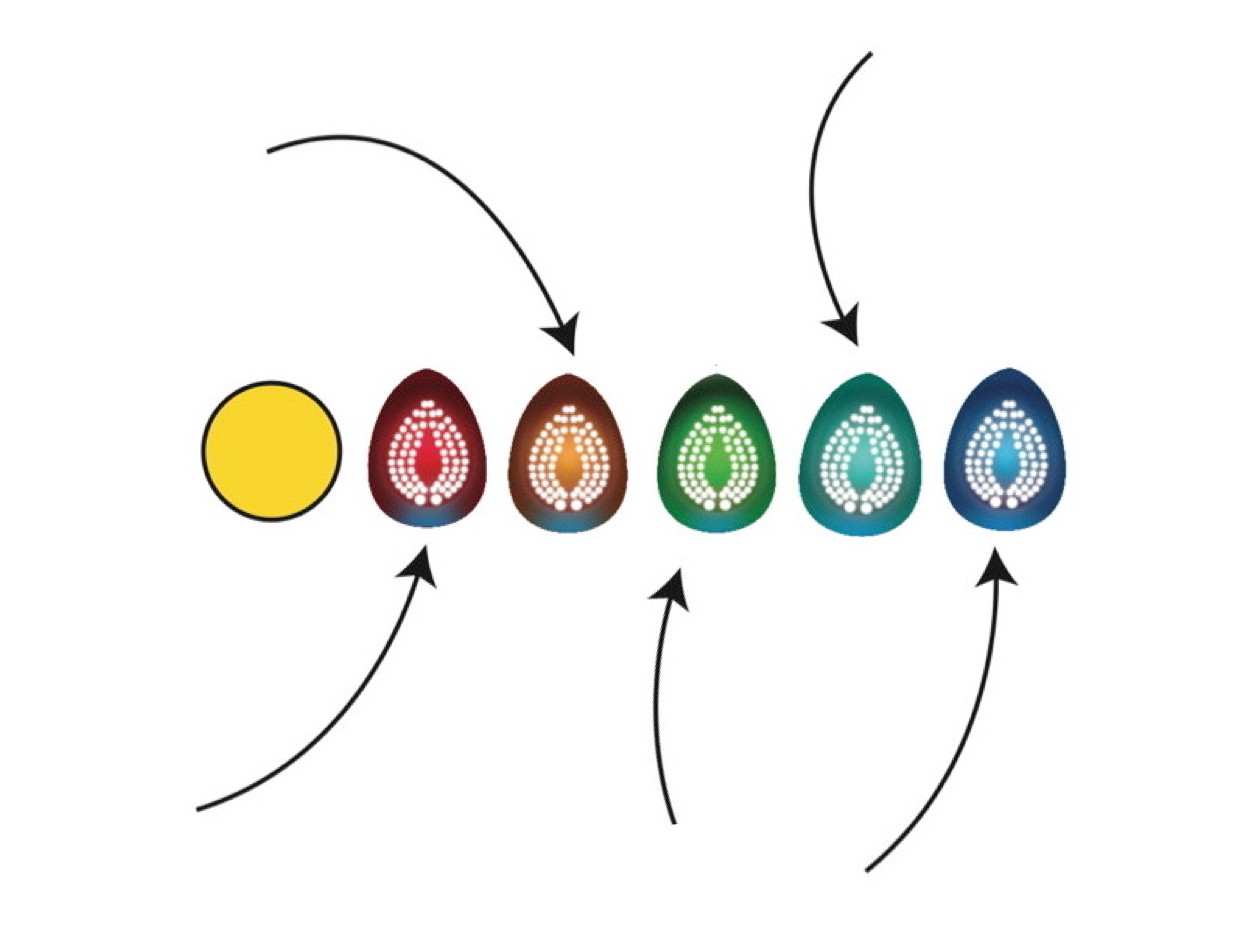

When in On Your Marks mode, the robots get in line. Every robot has a color assigned to it, and the robots line up in rainbow order.

Each robot knows which robots should be before and after it, and heads to the middle of those two robots.

When in Robophobia mode, the robots spread out from each other as much as they can.

You can decide whether or not the robots should also try to spread out from the people in the Robot Ring, and how fast the robots will try to get away.

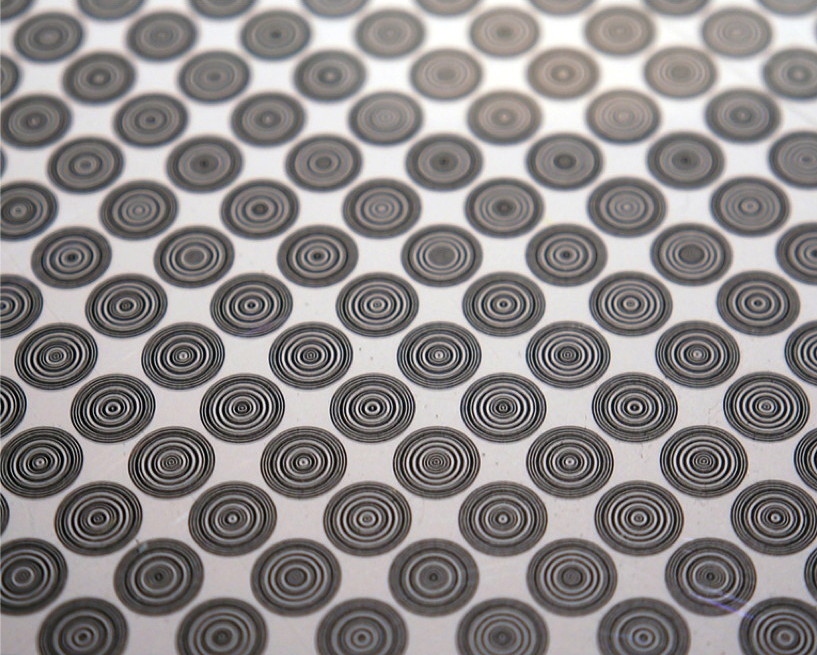

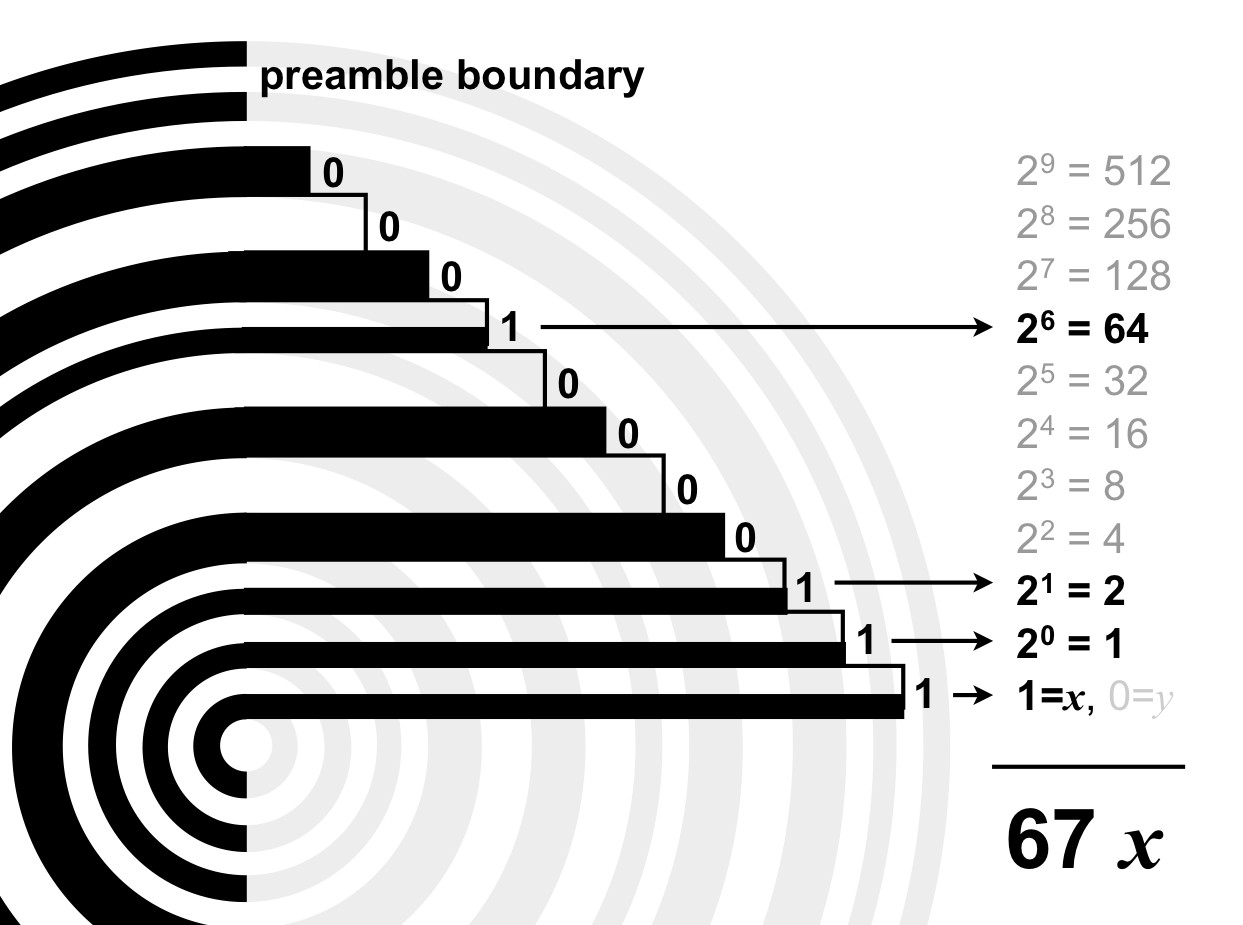

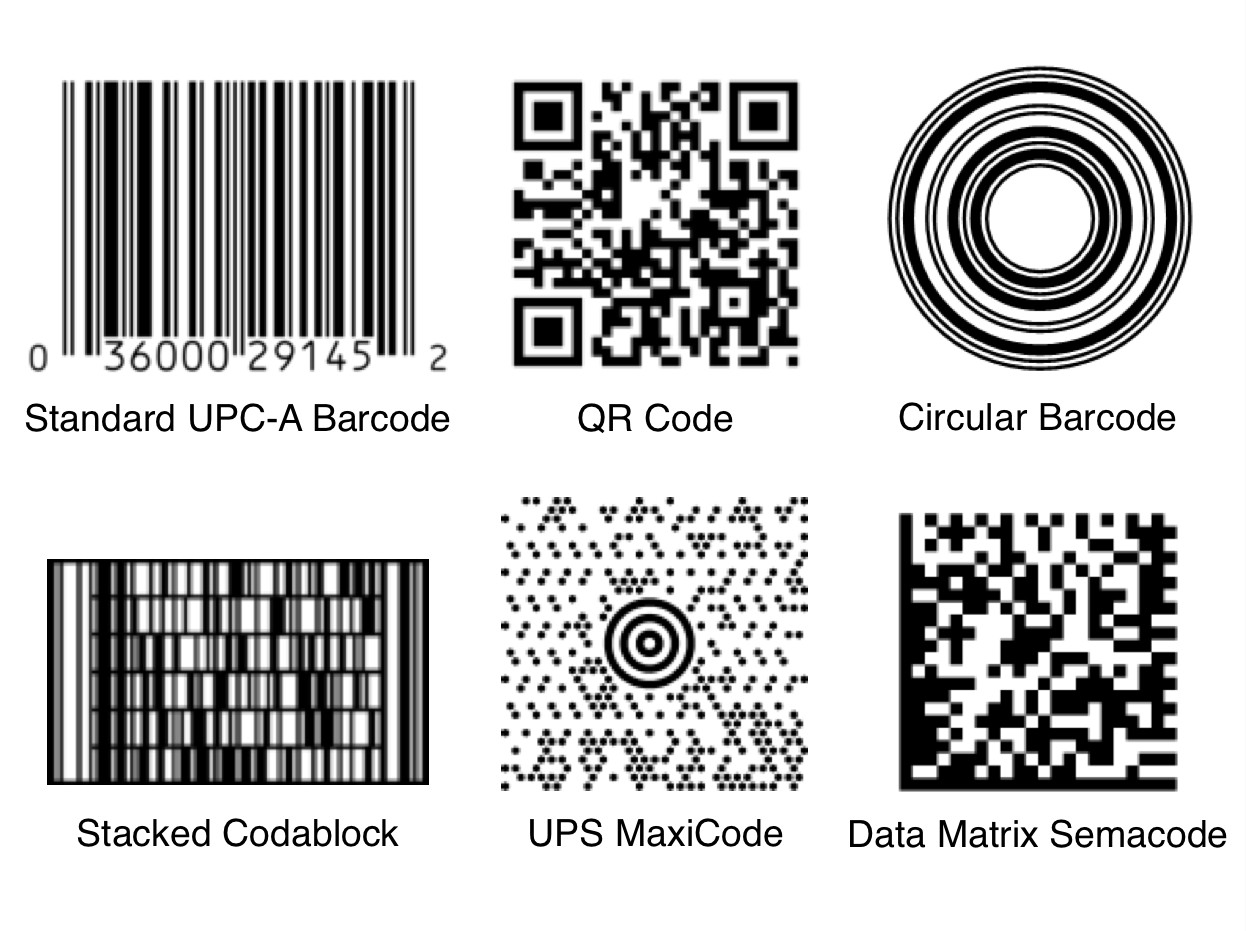

How do the robots know where they are? They read the round markers on the floor. The different rings on each marker are a code the robots can understand.

The ring pattern on each floor marker is a code for a number and a letter.

In this example the code happens to stand for the sum

and the letter x.

The number and letter help the robot figure out where it is.

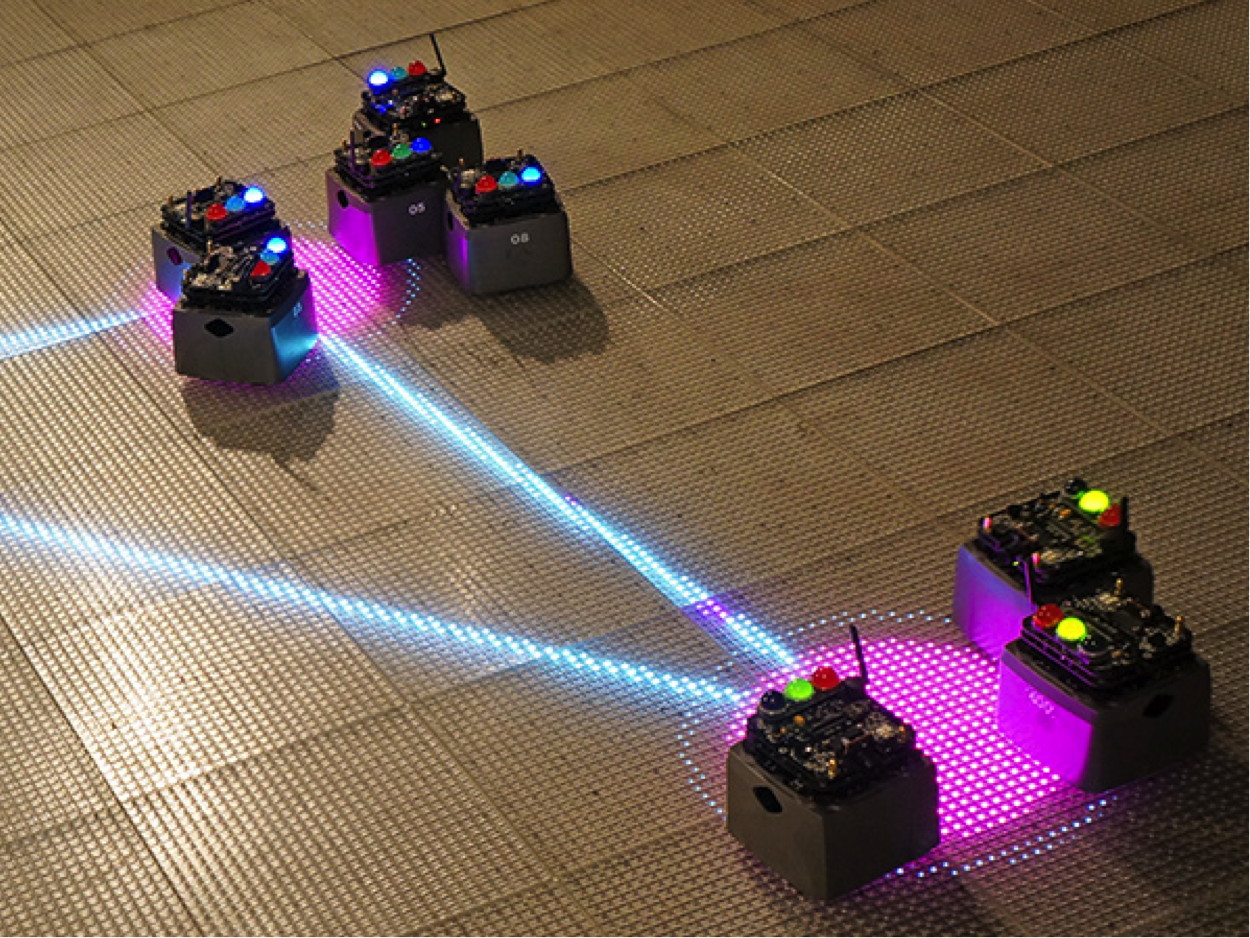

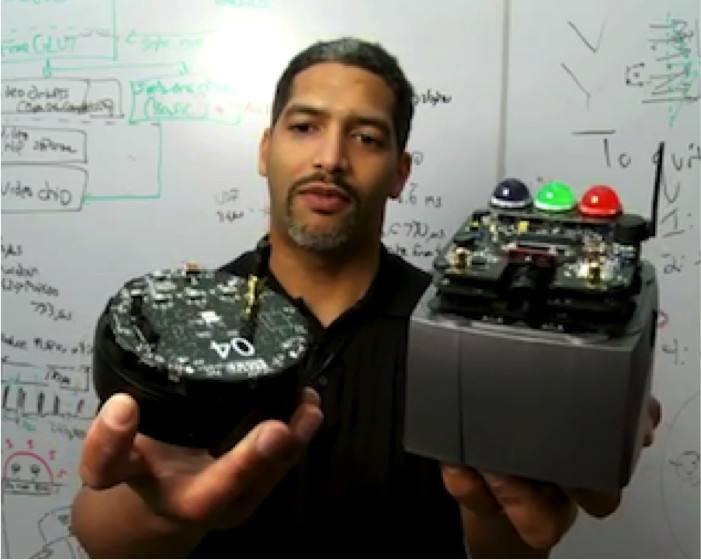

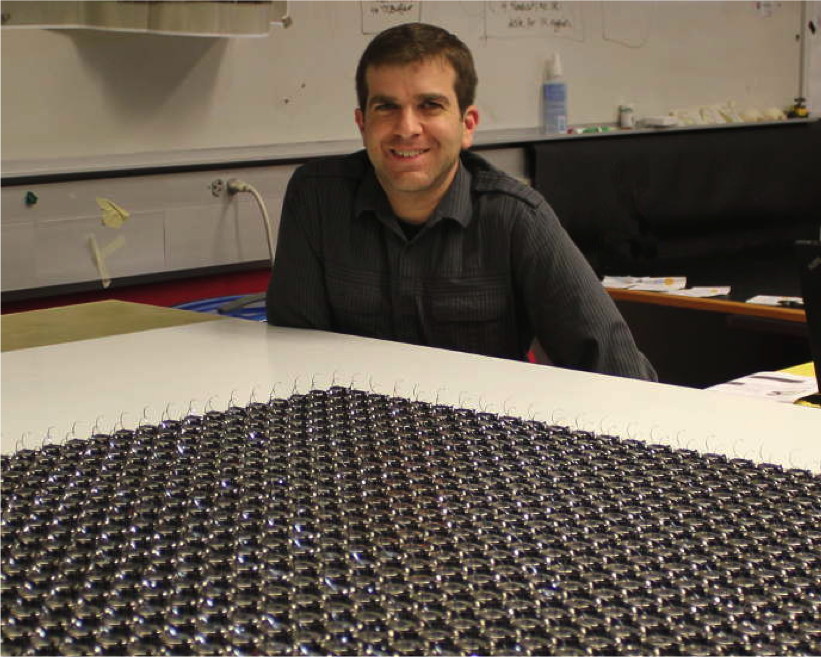

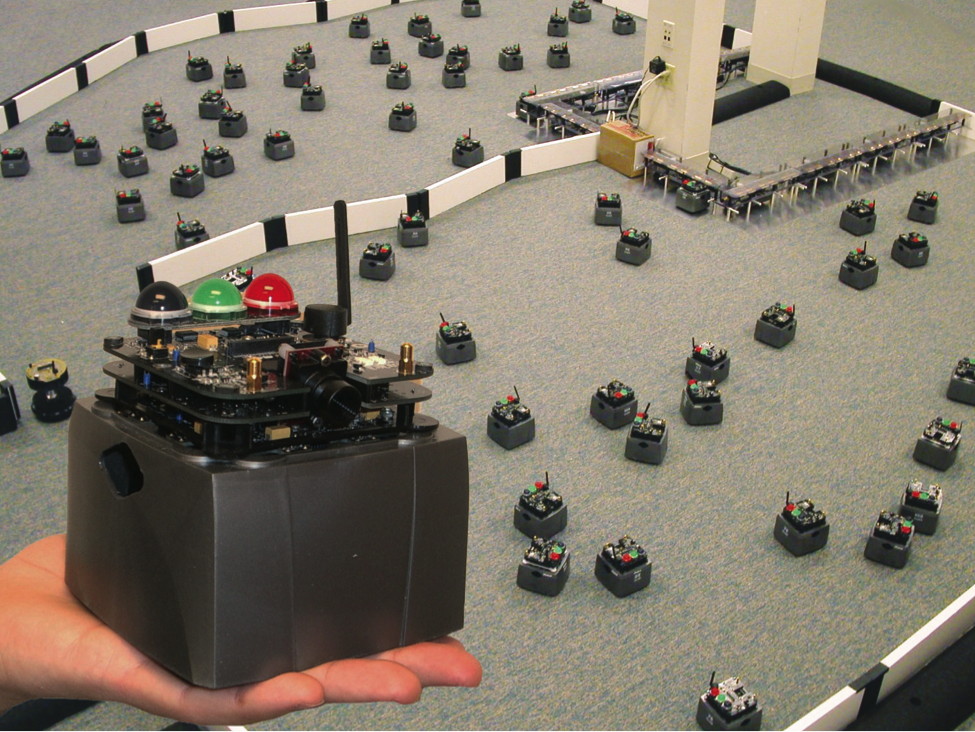

James McLurkin’s swarm robots in a demonstration at MoMath six months before this exhibit opened. The robots are illustrating some of the Robot Swarm behavior algorithms, communicating with each other and activating the Spanning Tree program on the Math Square floor.

Justin Windle’s implementation of Reynolds’ flocking simulator “Boids,” designed to mimic the collective behavior of flying birds. Although each individual bird follows simple local rules, the group moves together as if it were one organism.

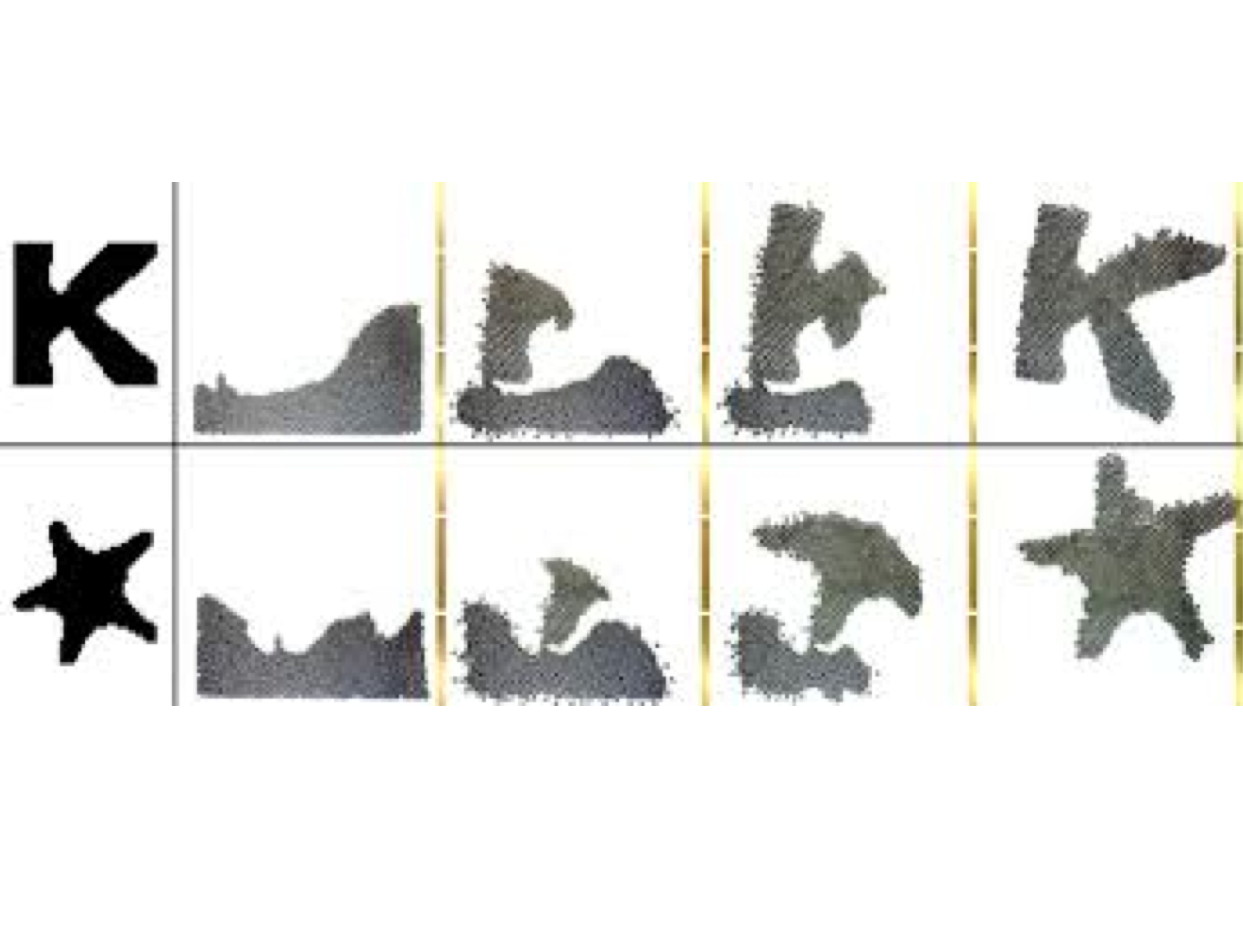

Harvard’s self-organizing Kilobot swarm of 1,000 tiny robots forming into “K” and “star” patterns, mimicking biological patterns in which myriad small cells or entities can use simple rules to form complex structures.

A pack of iRobot Create robots, which are modified versions of iRobot’s Roomba vacuum model. These ‘bots are souped up with control modules, serial ports, and input/output capability for studying robot design.

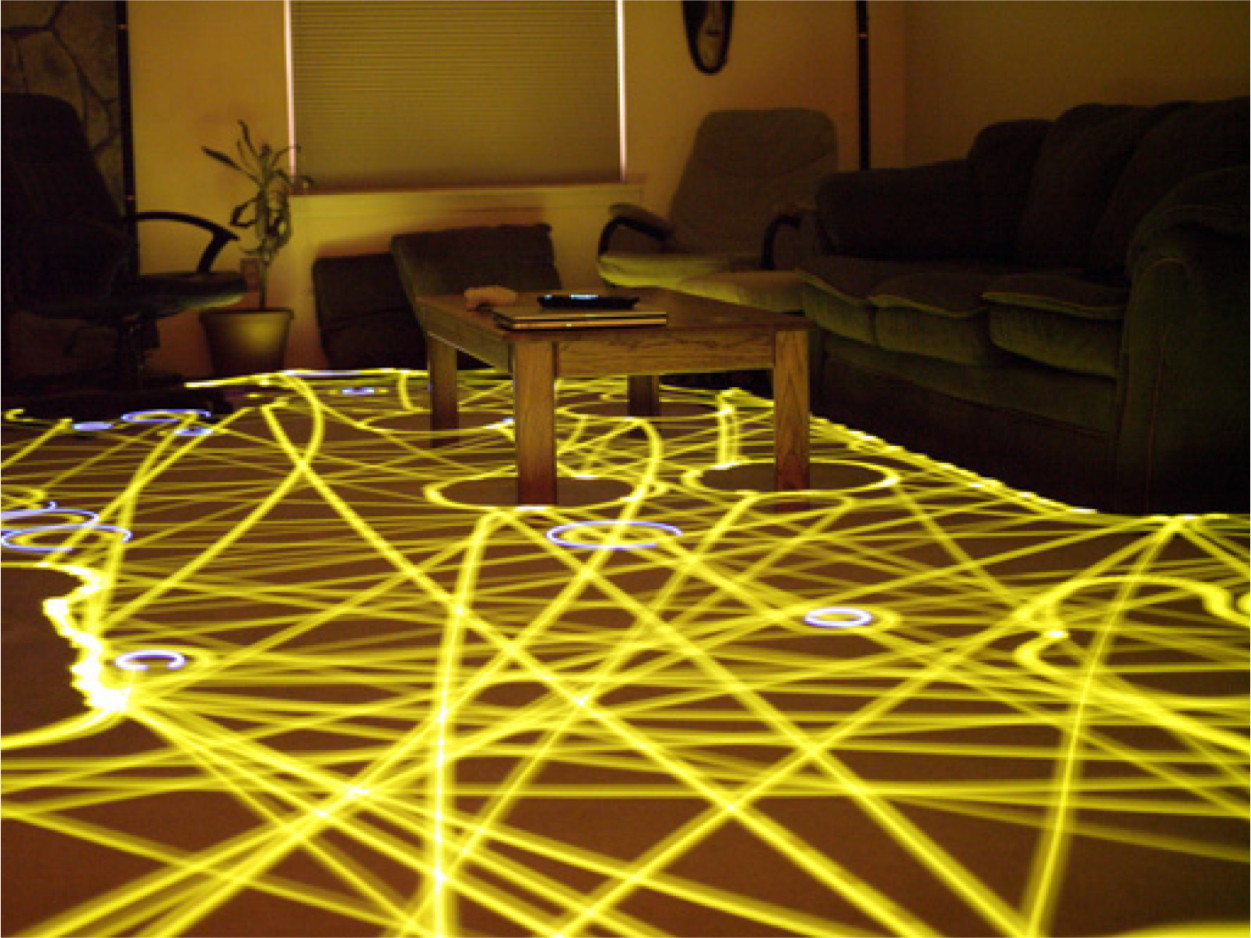

Attaching LED lights to a household cleaning robot and using long-exposure photography can reveal the beautiful patterns formed by the robot’s path-finding algorithms.

Mathematicians who study operations research look to swarms of ants and their fading pheromone trails to inspire new optimization techniques for finding optimal paths in graphs, such as the one shown in this Worlfram CDF Demonstration.

Locusts can travel in massive swarms that move like tank treads, with some locusts stopping to eat while others travel overhead. Predicting the movement of a locust swarm is difficult because it is based on the local decisions of a large amount of individual insects.

Wolves, like the ones in this diorama at the American Museum of Natural History, do not coordinate actions when hunting prey. Instead, each wolf follows just two simple rules: move to a safe distance close to the prey, and then move away from other positioned wolves.

In the cellular automata Game of Life invented by mathematician John Conway, cells on a grid turn on and off according to simple rules based on the states of their neighbors. This local behavior gives rise to beautiful interacting patterns that seem almost alive, like this Gosper glider gun.

The Shibuya scramble crossing in Tokyo, Japan. To avoid collisions, people must pay attention to their neighbors’ current and anticipated trajectories. The Extended Velocity Obstacle algorithm used in Robot Swarm does the same thing.

The glowing robots reacting to your movements would be right up the alley of mathematician Grace Hopper (1906 – 1992), a pioneer of computer science as well as a US Navy admiral. Hopper even invented programming languages like COBOL — which is still in use today!

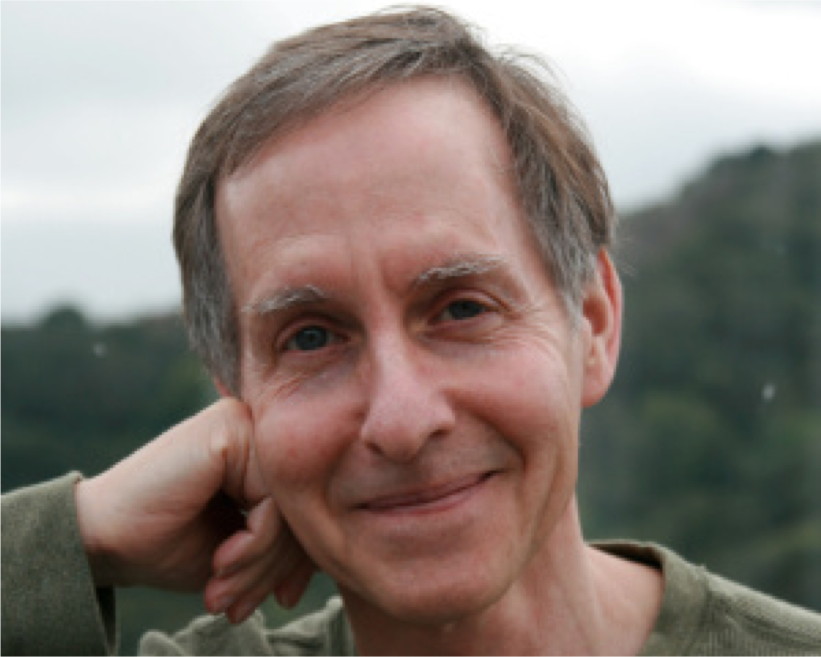

Maja Matarić pioneered early swarm robotics research while working on her Ph.D. in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence at MIT.

She is now a Professor of Computer Science, Neuroscience, and Pediatrics at the University of Southern California, where she also serves as the Vice Dean for Research at the Viterbi School of Engineering and the Director of the Robotics and Autonomous Systems Center. She is also a recipient of an NSF Career Award and Presidential Awards for Excellence in Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Mentoring.

Matarić’s Interaction Lab researches socially assistive robots: robots that possess human-robot interaction skills that allow them to provide non-contact assistance to help and collaborate with humans. Her current work includes developing robot-assisted caregiver therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders.

James McLurkin served as the roboticist-in-residence at MoMath in 2014, helping to build the robots and programming for the Robot Swarm exhibit. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science at Rice University and the Director of the Rice Multi-Robot Systems Lab (MRSL).

McLurkin is well-known for his work with swarm robots both for studying computational complexity of mathematical swarm algorithms as well as for sparking interest in young people. He has appeared numerous times on TV on programs such as NOVA Science Now, the WBGH show Thinking Big, and the Discovery Channel miniseries The Science of Star Wars. His pioneering work on communication, navigation, and hands-free operation of robot swarms was key to the development of the robots in this exhibit.

Craig Reynolds is an applied artificial intelligence software engineer at Staples Innovation Lab in San Mateo, California. He has also worked as a research game developer at the Center for Games and Playable Media at the University of California, Santa Cruz and as a senior researcher at Sony Entertainment. In 1998, he won the Academy Scientific and Technical Award for “pioneering contributions to the development of three dimensional computer animation for motion picture production.”

In his work, Reynolds modeled the behavior of autonomous non-player characters in games by mimicking the behavior of animal systems in the real world such as flocks of birds and insects. He also created the Boids artificial life flocking simulation, in 1986. He is an editorial board member for four scholarly journals and has written 18 research papers with a total of nearly 10,000 citations.

Michael Rubenstein is a researcher in the Self-organizing Systems Research Group of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, where he works on projects involving robotic shape self-assembly, massive robot swarms, and low-cost student-accessible robots. He holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the University of Southern California. Rubenstein’s work with the Harvard Kilobot team is about collections of thousands of tiny robots, whose local actions mimic those of ant swarms who can work collectively to create formations and even carry objects. He has published over a dozen articles including his recent paper Programmable self-assembly in a thousand-robot swarm, which appeared in Science. He appears regularly on TV and other media such as the BBC News, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, and National Geographic.

David Siegel is the Co-Chairman and co-founder of Two Sigma Investments, a technology company that applies a rigorous, scientific method-based approach to investment management. Prior to co-founding Two Sigma, David was Chief Technology Officer and Managing Director at Tudor Investment Corporation. After earning his doctorate, David joined D. E. Shaw & Co. and rose to become the company’s first Chief Information Officer. A graduate of Princeton University, David received a PhD in computer science from Massachusetts Institute of Technology where he studied at its Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. David has had a lifelong interest in building intelligent computational systems and continues to actively pursue this mission at Two Sigma today. He is a trustee of Carnegie Hall and sits on the Board of Directors for Hamilton Insurance Group, the Code-to-Learn Foundation, and NYC FIRST.

David has a background and interest in robotics himself, and his insightful questions and advice helped shape the direction of the design of Robot Swarm.

In addition, MoMath is grateful to the Siegel Family Endowment for funding its roboticist-in-residence and helping make the Robot Swarm exhibit possible.

Three Byte is the New York City firm of Olaf Rossi, Chris Keitel, Amichai Levy, Sam Goldman, and Sam Engel. Three Byte built the MoMath Robot Swarm exhibit, as well as MoMath’s registration stations, informational kiosks, AV system, and Mathenæum exhibit. Their other projects include work for the Museum of Modern Art, Sony, HP, and Sprint.

Three Byte Intermedia focuses on developing custom interactive applications for museums, public spaces and art installations. They research hard problems and create turn-key systems combining best of breed hardware, software and innovative ideas. Three Byte’s software runs permanent installations in New York around the world helping to facilitate memorable experiences and great impressions.

Household robot vacuums use different types of programs to figure out how to move around a room.

Some, like the iRobot Roomba shown here, use nearby information to make decisions — just like the Robot Swarm. Others, like Neato’s Botvac robot, instead make a map of the whole room before starting to clean.

A group of fish that moves together in a pattern is known as a school. Moving together helps fish protect themselves from predators like sharks.

The Swarm mode of this exhibit is based on the way that fish move together in schools.

Circular barcodes are just one example of the many types of barcodes that we use today for scanning by cellphones and for mailed packages.

One reason that circular barcodes were chosen for this exhibit is that they can be scanned by the robots from any direction.

An early example of a robot swarm was the Nerd Herd, part of Maja Matarić’s work at the MIT AI Lab in 1994.

Matarić was interested in breaking down swarm behavior into small rules. Her work laid the foundation for future swarm research and the robots used in this Robot Swarm exhibit.

The robots that inspired the design of the ones in MoMath’s Robot Swarm exhibit are the iRobot Swarm robots, created by the company iRobot in 2003.

The iRobot Swarm was created to behave like a colony of insects so that the iRobot roboticists could study group behavior patterns.

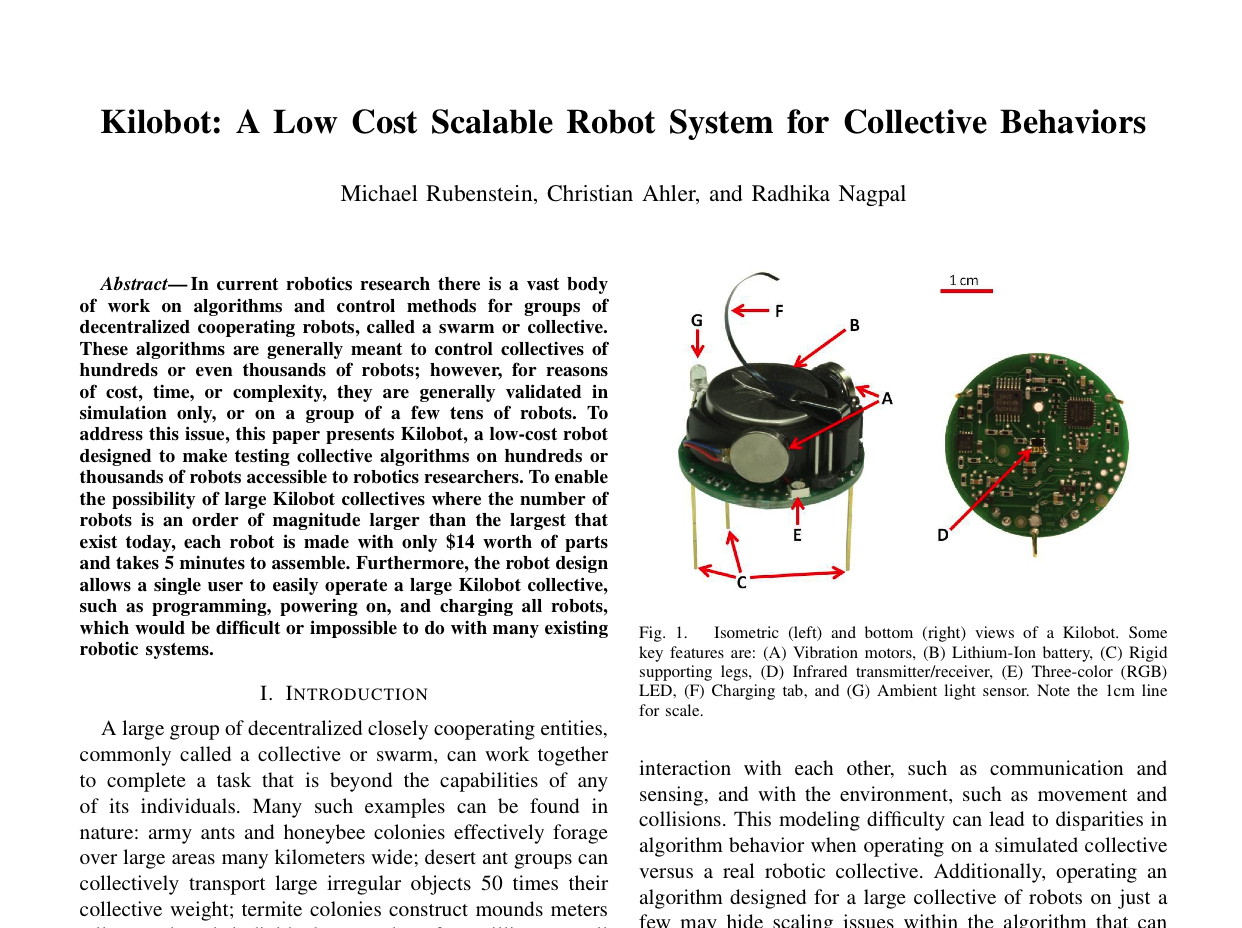

What happens when you have a swarm of over 1,000 robots? That’s what Michael Rubenstein’s team is trying to answer at Harvard University with the Kilobot swarm.

Each of the Kilobot robots is tiny and can do only simple tasks, but working together they can make shapes and patterns.

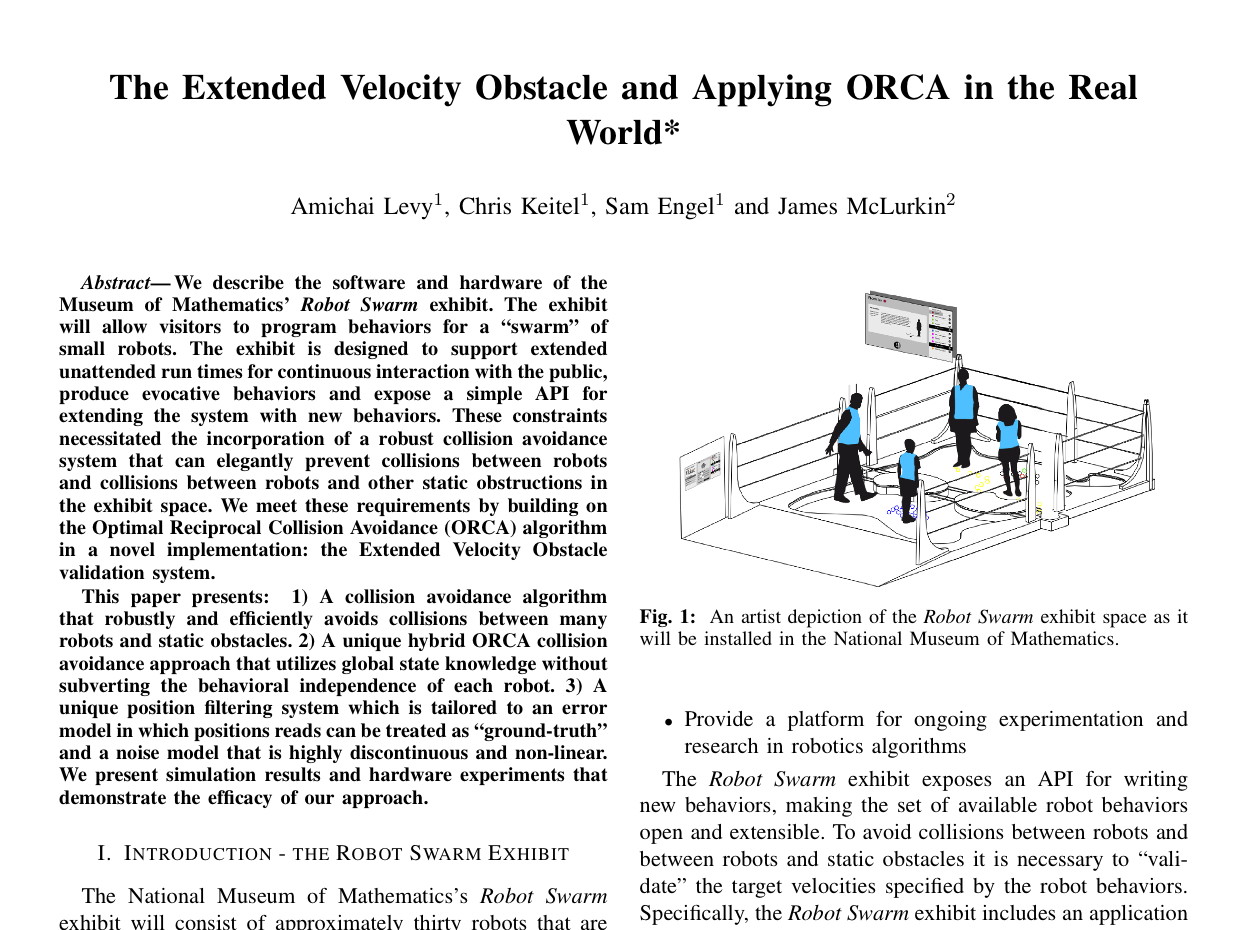

Amichai Levy, Chris Keitel, Sam Engel, and James McLurkin

This paper describes an extension of the standard Optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance algorithm to include consideration of nearby robots’ target velocities.

Craig Reylonds, Sony Computer Entertainment America

This paper investigates behavior layers governing the action of NPCs, or autonomous non-player-characters, in video games.

James McLurkin, Rice University

This paper examines communication and navigation algorithms in multi-robot computational models such as the one in Robot Swarm.

Rubenstein, Christian Ahler, and Radhika Nagpal.

This paper describes hardware, maintenance, and programming of a swarm of simple robots used for testing collective algorithms and scalable operations.

Daniel Shiffman, NYU Interactive Telecommunications Program

A programming textbook with code examples using the Processing language to model evolutionary and emergent behaviors.

New York Times Science Times article about the design, construction, operation, and opening of the MoMath Robot Swarm.