Wait a second – I think we have a mischievous monkey among us! Go ahead and count how many red monkeys and how many blue monkeys you see. Then grab the handle and pull it toward the other side of the circle to reorient the ring. Now count the monkeys! Has one…changed color? (And if so, how did he dye his fur so fast?)

Need a hint? This is a geometric illusion where objects seem to vanish. When the ring is rotated, the parts belonging to each monkey change. But do all the monkeys get the limbs they lost?

Take another look at the red monkeys playing in front of you, with the handle on the left side. If this big circle were a clock, there would appear to be a monkey at 10:00. But when the handle is pulled to the right side, there is no longer a 10:00 monkey. This monkey is like the last man on the face puzzle on the previous page, except not a single piece of him is above the dotted line – not a paw, not a tail, not event a top hat! The entire monkey leaves the 10:00 position (just like the last man in the previous example would if he didn’t have a hat) and nothing replaces him.

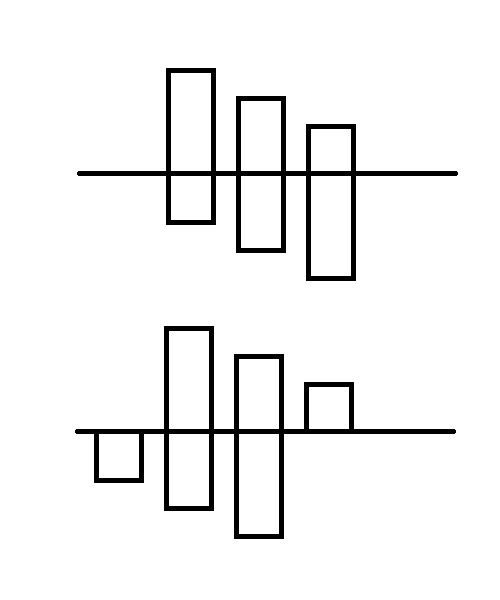

Monkeys might be a bit tricky, but simple geometrical vanishes are not hard to make. On a strip of paper, draw a horizontal dotted line. Then pick an object that looks like itself even if you cut some of the top or bottom off – like a skyscraper or a tree. Draw some of those objects evenly spaced across the horizontal line. but make sure that the one on the far left is completely above the line and the one on the far right is completely below the line. Now cut along the horizontal line to make two strips, and watch the objects disappear as you slide the bottom strip back and forth!

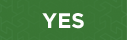

Here is the original puzzle that inspired the one you see before you. It is called “Get Off the Earth,” and was created by Sam Loyd. Try counting the men in both images!

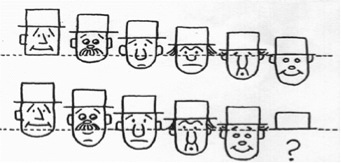

Here is another geometrical vanish created more recently (1956) by Canadian puzzle maker Mel Stover. On the left there are six blue pencils and seven red pencils. But when everything below the line is shifted three places (the picture on the right), there are seven blue pencils and six red pencils.

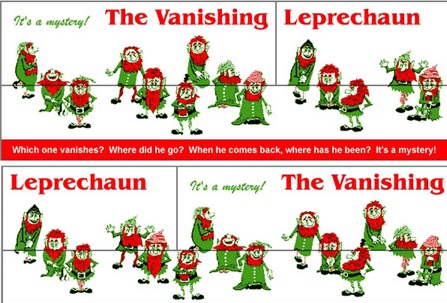

This is another famous geometrical vanish: “The Vanishing Leprechaun,” created by Ms. Pat (Patterson) Lyons in 1968. The two sections of the top half of the puzzle (divided by a vertical line) switch places, and a leprechaun disappears!

Perhaps the trigonometric series research of Russian mathematician Nina Bari (1901 – 1961) would come in handy to find that missing (or extraneous) monkey in this exhibit. Bari had a long and distinguished career in Moscow, presenting the results of her important work at many international meetings.

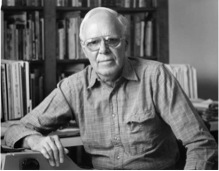

Though the original puzzle was created by Sam Loyd, it was the great Martin Gardner (1914-2010) who made the “Get off the Earth” puzzle famous in the book Mathematics, Magic and Mystery.

Martin Gardner was the oldest of three children and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Martin Gardner became interested in puzzles at a young age—since the day his father gave him a copy of Sam Loyd’s Cyclopedia of Puzzles, in fact. But Gardner was interested in many things: not just mathematical puzzles, but also literature, philosophy, and religion. He spent much of his life writing about “recreational” math, mathematical games and puzzles that can be studied without formal training. For many years he wrote about “Mathematical Games” in the journal Scientific American. He published more than seventy books about mathematics and other subjects, such as literature – and sometimes both at the same time. (He was a big fan of the playful mathematical logic in Alice in Wonderland–author Lewis Carol was also considered a recreational mathematician, along with author Henry Dudeny, mathematician John Horton Conway, and many others.)

Martin Gardner’s work has made him the most famous recreational mathematician of our time.

Monkey Around was personally recommended to MoMath by Martin Gardner.

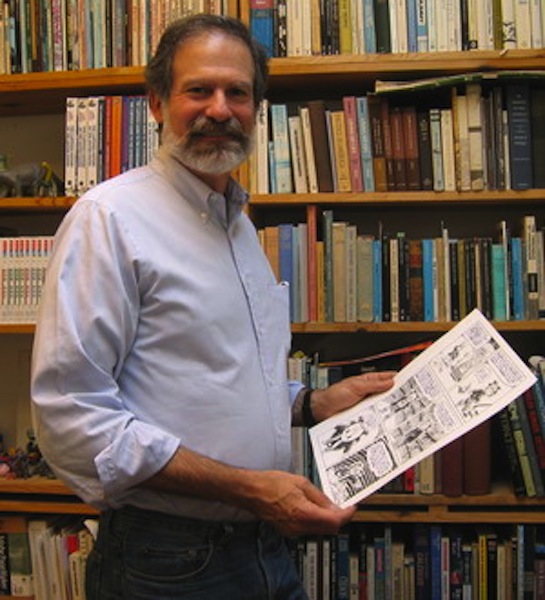

Author of The Cartoon Guide to Calculus, Larry Gonick drew the monkeys featured in MoMath’s rendition of Monkey Around.

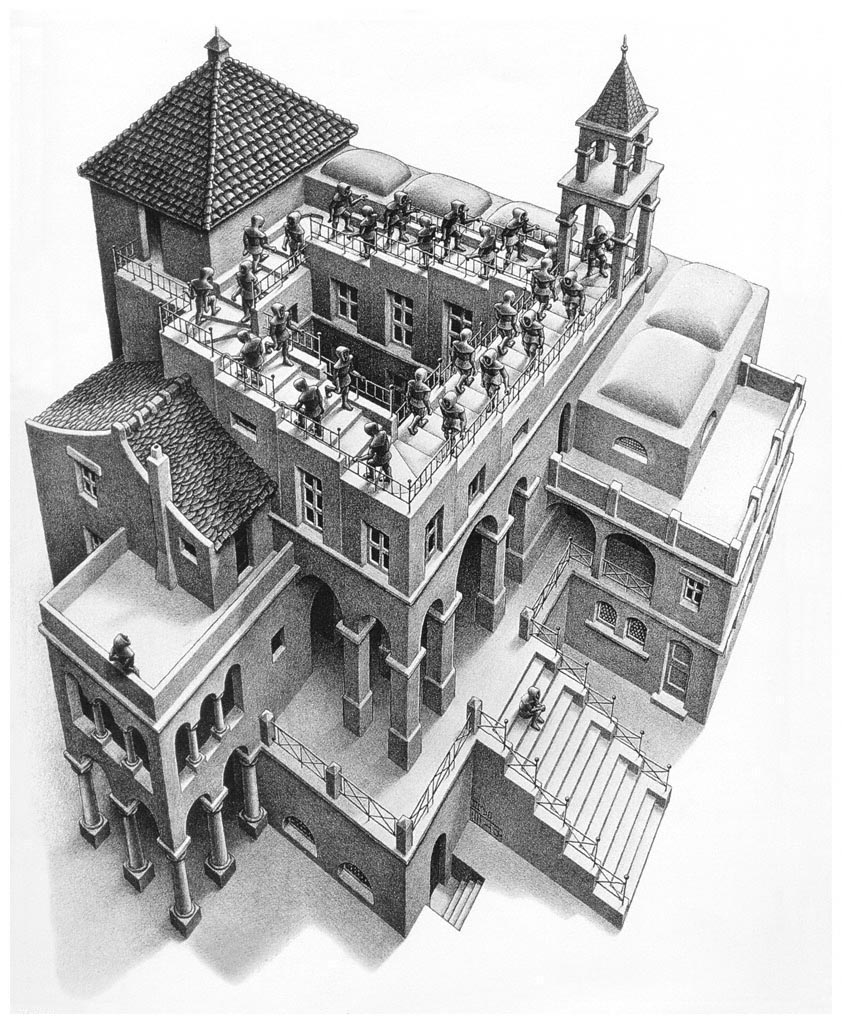

What are the uses of optical illusions, you are ask? Well, first and foremost, to amuse viewers like you! The most popular creator of visual optical illusions is probably M. C. Escher, who drew the impossible – literally objects that could not exist in three dimensional space as we know it, as in this picture. For most of his life, Escher made a living by traveling around Europe, sketching and selling his prints. Other recreational mathematicians, like Martin Gardner and Sam Loyd, had long and fulfilling careers compiling and creating puzzles for popular books.

Optical illusions in general are not so much “put to use” as “discovered,” since there are many optical illusions found in nature. Mirages, for example, are created when light rays are bent and produce another copy of an object where it doesn’t exist. So if you’re wandering around in the desert and you see a lake in the distance, don’t get your hopes up! Those upside down trees might just be bent light rays, as in this picture. The optical illusions that nature hands us show us that our senses can be trusted, but at times are easily fooled. Therefore the “applications” of optical illusions are to teach us that to be successful human beings, our senses need to work together with our minds.

Optical illusions have fascinated people for a very long time, because optical illusions are not only man-made but often occur in nature. For instance, if you start a fire in your backyard (don’t, but just imagine you did…) and look over the fire at some trees in the distance, the trees might seem to wiggle. Of course the trees are not dancing around eagerly anticipating s’mores. Rather, you are viewing the trees though heat waves that distort the image on the other side. It was relatively recently though (the 1800s), that humans started studying “visual illusions.” Since then, people have enjoyed puzzling out optical illusions and even creating their own.

Monkey Around was based on a similar puzzle called “Get Off the Earth” created over a century ago (in 1896, to be exact) by a man named Sam Loyd (1841-1911). He was the youngest of eight children and grew up in Philadelphia. (That’s only 25+25+25+25 miles from where you are now!) Even as a young boy he loved puzzles—especially puzzles related to chess. As he got older, though, he began creating puzzles of his own, of all types, and publishing them in books. His most well-known work was the Cyclopedia of Puzzles, which contained over 500 puzzles written for, as the man himself put it, “that legion of people, young and old, who delight in puzzle-solving.” The book even contained some “prize puzzles,” and the first person to send in the correct solution was awarded 100…but we can promise you lots of fun!