Suppose you had only tubes of capacity 3 and 5. Could you somehow use them to measure exactly 4 balls? What other quantities could you measure using these two tubes?

How does this change if you use tubes of capacity 4 and 6?

If you’ve experimented, you’ve likely noticed that there are only a few “interesting” things you can do: completely fill an empty tube, completely empty a full tube, transfer the entirety of one tube into another, or transfer the contents of one tube into another until the receiving tube is at capacity. (Why is filling a partially full tube counterproductive?)

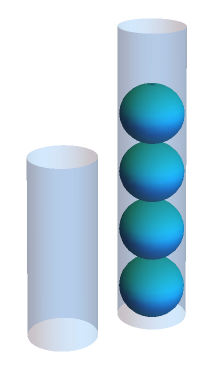

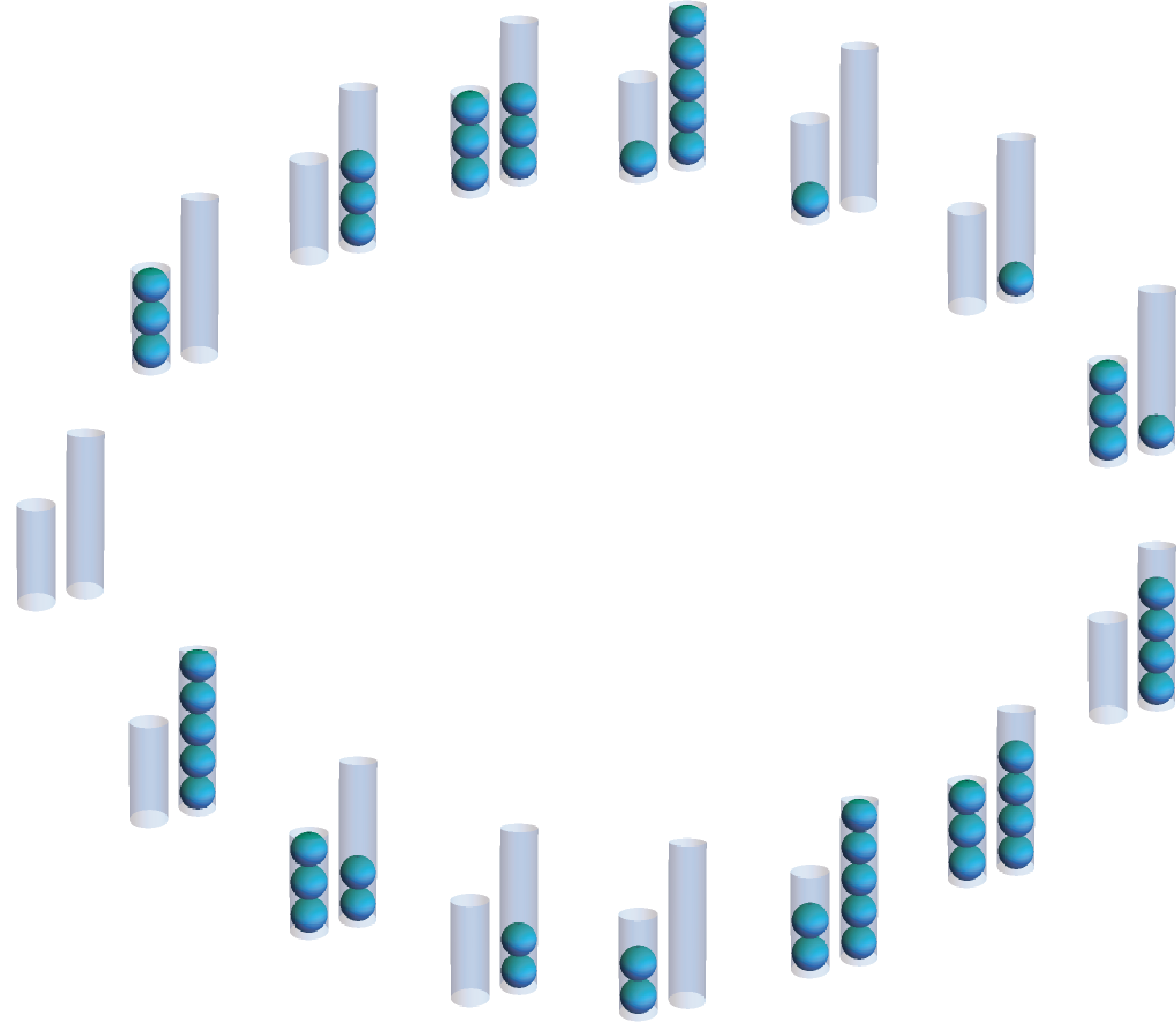

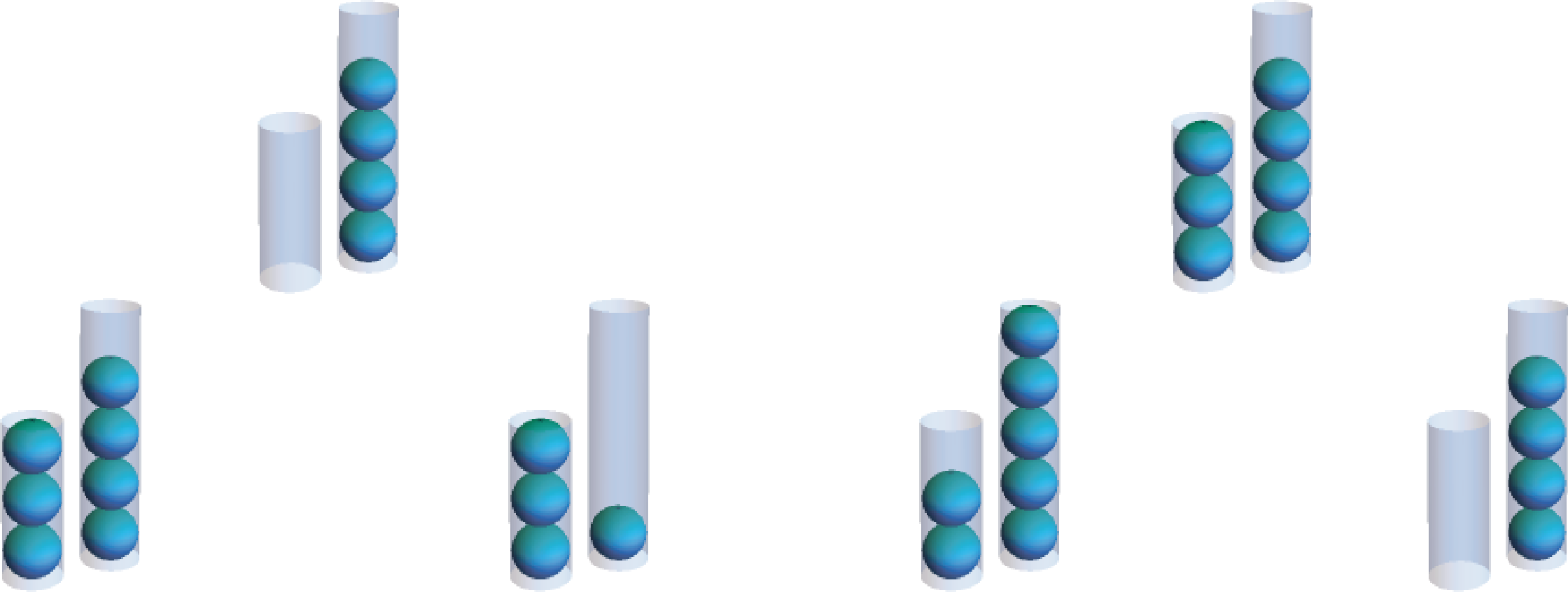

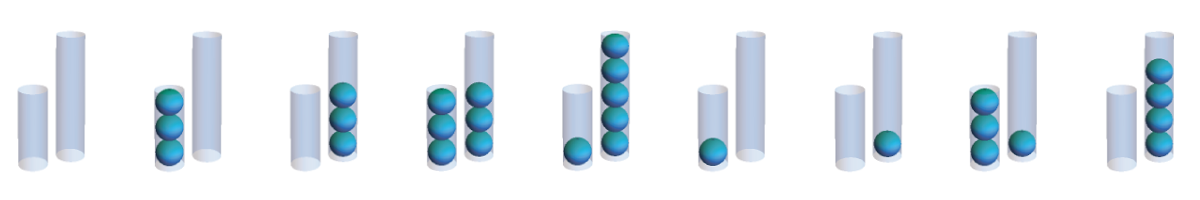

Using these moves, you might stumble upon one of the two solutions to the right. In the top solution, the smaller tube is repeatedly filled and then its contents are transferred to the larger tube. Once the larger tube is full, it is dumped and then the remainder of the small tube’s contents are transferred, resetting the cycle. The lower solution is similar, except the larger tube is filled and its contents transferred to the smaller tube. (Notice that these two solutions together measure all quantities of 1-5 balls along the way!)

If you keep applying the procedure of filling the smaller tube and transferring to the larger after you’ve successfully measured four balls, you’ll find that you end up reproducing the procedure of filling the larger tube and transferring to the smaller tube in reverse! Notice that in this cycle the larger tube ends up measuring every quantity from 0-5 balls. Does such a procedure exist for every pair of tubes?

As you start a puzzle with two empty tubes in hand, you might note there are a few easy configurations to achieve: both tubes empty, both tubes full, the small tube empty and the large tube full, and the small tube full and the large tube empty. Since you can completely empty either or both tubes at any time, these four configurations are easy to get to from any configuration. In this sense, “interesting” configurations must feature one of the tubes being partially filled.

At each stage, you might note that at least one of the tubes is empty or full. (Why must this be the case?) If one tube is partially filled, there are only two interesting types of moves to make: If the other tube is empty, you may transfer from the partially full tube to the empty tube or fill the empty tube. If the other tube is full, you may transfer from the full tube to the partially full tube or empty the full tube.

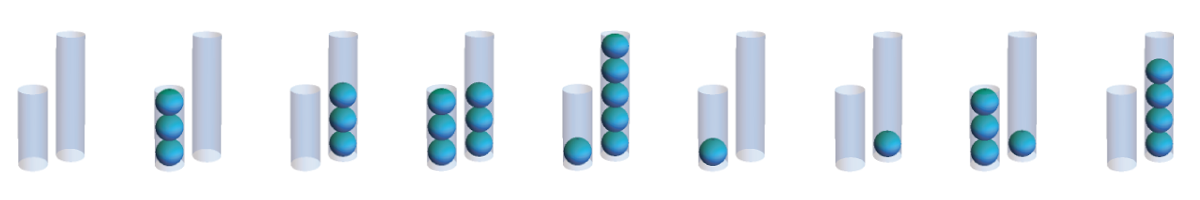

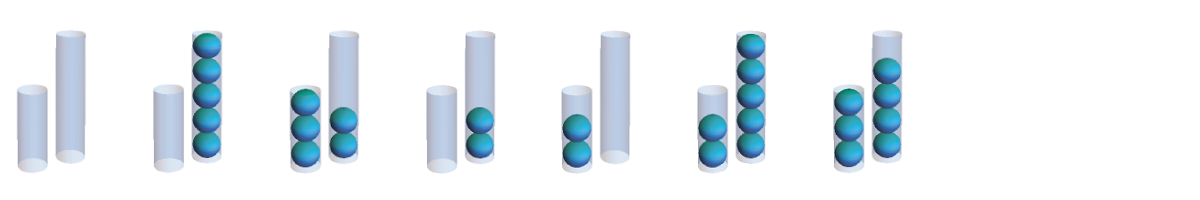

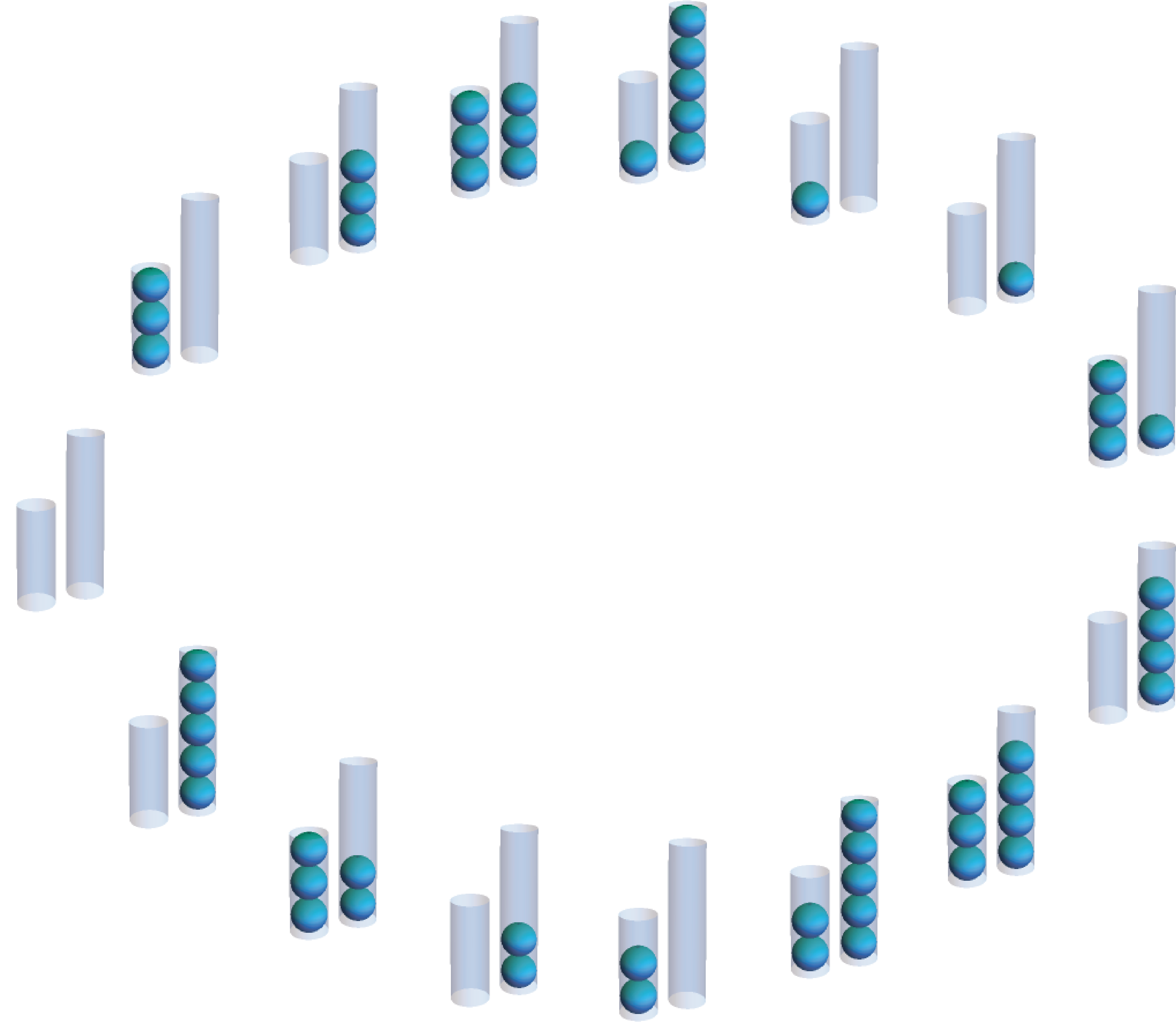

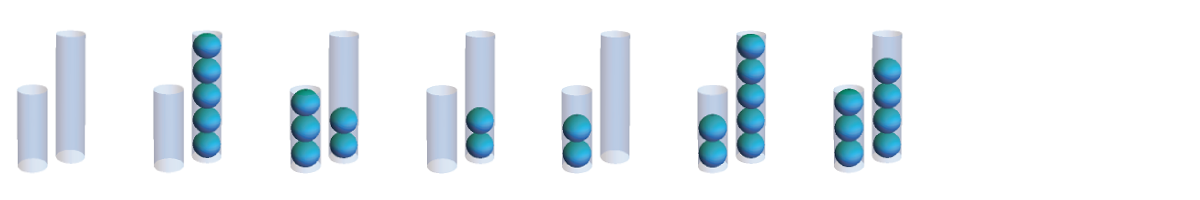

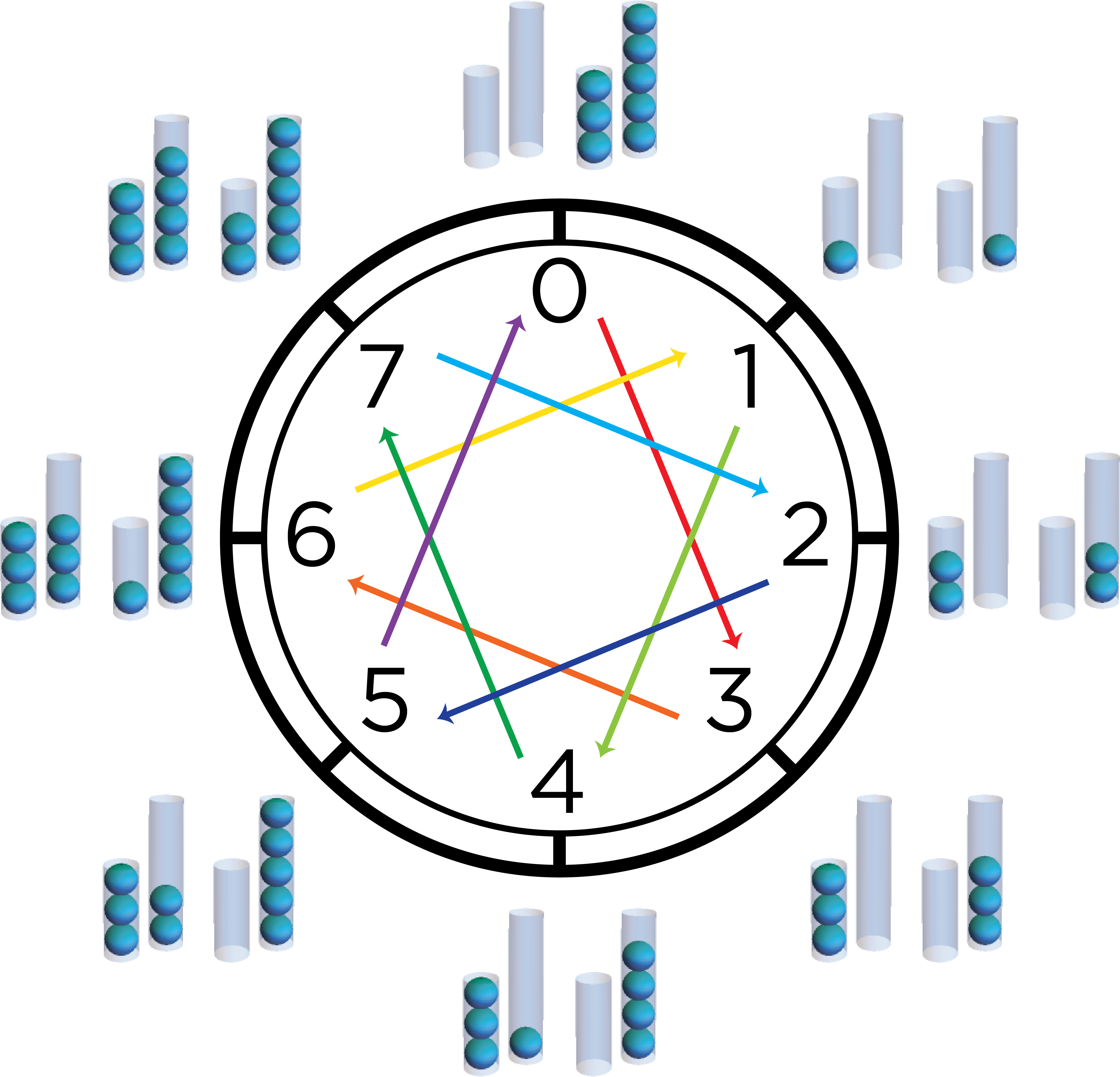

For the tubes of capacity 3 and 5, if we ignore the state where both tubes are full, then we end up with this cycle of configurations, organized by being one “interesting” move away from each other. If we traverse the cycle clockwise, we read it as always filling the capacity 3 tube and dumping the capacity 5 tube. Since transferring doesn’t change the total number of balls in the system, this means that the total number of balls always has the form , where the capacity 3 tube has been filled times and the capacity 5 tube has been dumped times. Similarly, if we read it counterclockwise, we always fill the 5 tube and dump the 3 tube, so the total number of balls in the system has the form .

If we want to find a way to measure exactly four balls, then we can either try to solve or .

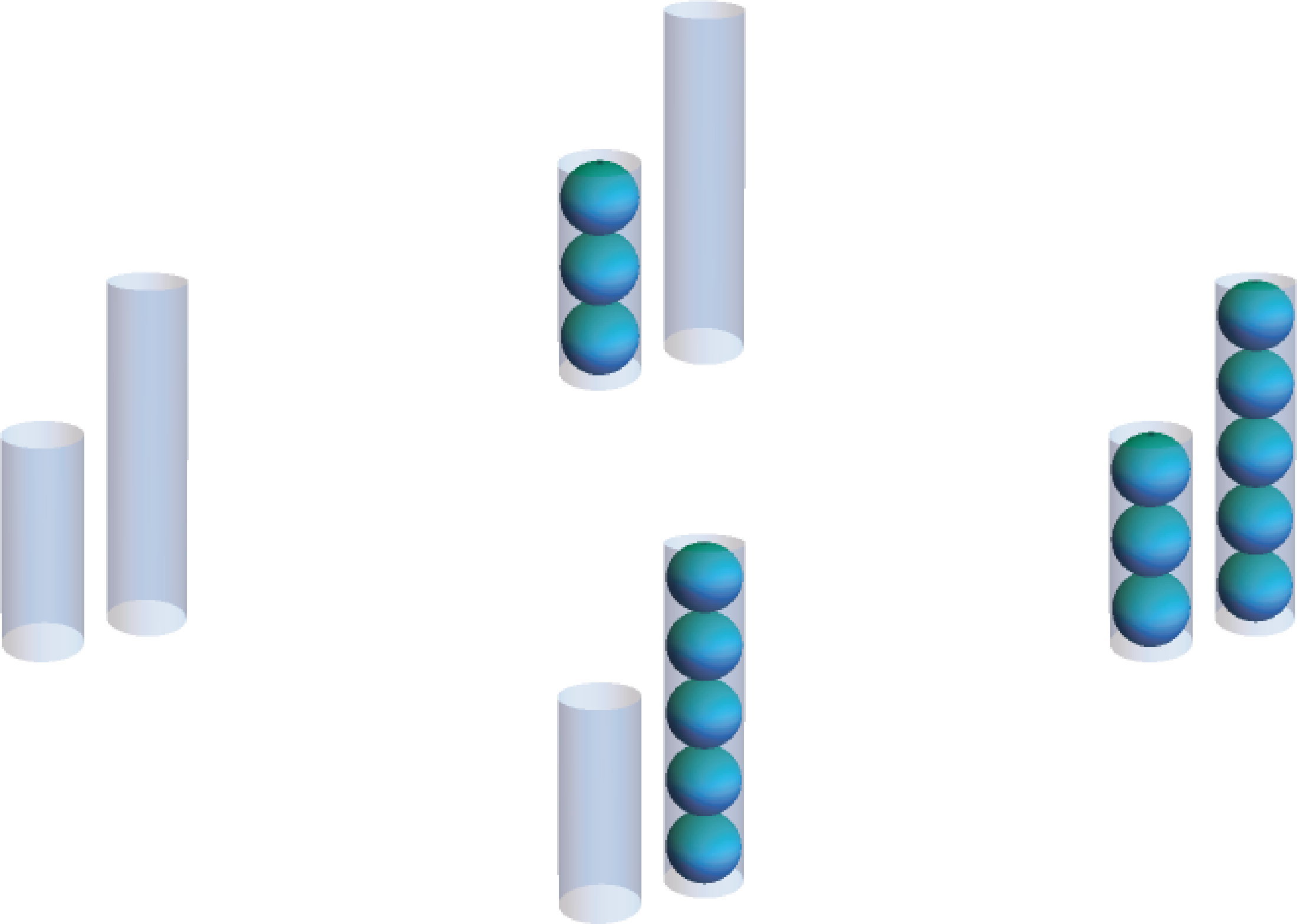

A solution to is , which translates to filling the 3 tube three times and dumping the 5 tube once. This is the solution shown above on the right, where we fill 3 and transfer, fill 3 and transfer, dump 5 and transfer, and fill 3 and transfer.

A solution to is , which translates to filling the 5 tube twice and dumping the 3 tube twice. This solution is shown below on the right, where we fill 5 and transfer, dump 3 and transfer, and fill 5 and transfer. (Dumping 3 one more time as our solution suggests would ensure there are exactly 4 balls in the system, whereas we have already measured 4.)

Lurking in the background of these puzzles are some concepts from number theory. Given two numbers, we can list all of the positive integers that evenly divide each. A common divisor is a number that appears in both lists while the greatest common divisor is the largest number appearing in both lists. For example, the divisors of 3 are and the divisors of 5 are , so . Pairs of numbers like 3 and 5 with a GCD of 1 are called relatively prime. On the other hand, , so 4 and 6 are not relatively prime.

Suppose two numbers are evenly divisible by 3. What can we say about their sum? Their difference? It turns out both of these must be divisible by 3, as well! More generally, if two integers and are divisible by , then must also be divisible by for any integers and . In particular, must divide . This means that the only quantities of balls we should expect to be able to measure with tubes of capacity and are those that are multiples of . With tubes of capacity 3 and 5, we were able to measure any number of balls from 1-5. What quantities might we expect to measure with tubes of capacity 4 and 6?

When divisibility comes up, it’s often useful to use modular arithmetic. Modular arithmetic is like the arithmetic we do when we tell time. At 10 o’clock, what time will it be in 5 hours? It’s not quite so simple as addition: . While some people use a 24 hour clock, most of us would likely read this new time as 3 o’clock, since once the small hand moves past 12, the next hour is 1 o’clock. Another way to think about this is that, after adding the times, we subtract 12 to give us a time in the 1-12 range. In our example, , which gives 3 o’clock. Similarly, we could ask what time it will be 40 hours after 10 o’clock: and , so 2 o’clock.

When using clock arithmetic, there is a special number called the modulus where the reset occurs. With time, the modulus was 12. If we choose a number as our modulus, then a number’s residue is the remainder we get when we divide by . Suppose we want to reduce 31 . We would note that 7 goes into 31 4 times with a remainder of 3, so . We use a three-barred equals sign to say two numbers have the same residue. Two numbers have the same residue if their difference is a multiple of . In our example, and .

Returning to our puzzle with tubes of capacity 3 and 5, the total capacity of the system is 8. What happens if we track the total number of balls in the system ? Since transferring doesn’t change the number of balls in the system, it doesn’t affect the number of balls . Every value 0-8 ends up representing a pair of configurations that are a transfer apart, except for 0.

If we think about the strategy where we fill 3 and dump 5, our effect on the system is always +3 or -5. However, , so . Our algorithm then simply alternates between adding 3 and transferring. If you start with the empty tubes, you can reconstruct the algorithm by following the arrows.

The ideas above give us a nice way to estimate the quickest solution. Suppose we have tubes of size 3 and 7 and our target number is 4. Adding copies of 7 , we have . On the other hand, . We will measure 4 balls more quickly if we start by filling tube 7 instead of tube 3. (It’ll go about four times faster, in fact!)

The unusual water-pouring puzzles of this exhibit require similar traits — tenacity, ingenuity, grit — as those exhibited by Britain’s Joan Clarke (1917 – 1996), a cryptanalyst working at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, who helped to decrypt the German Enigma code.