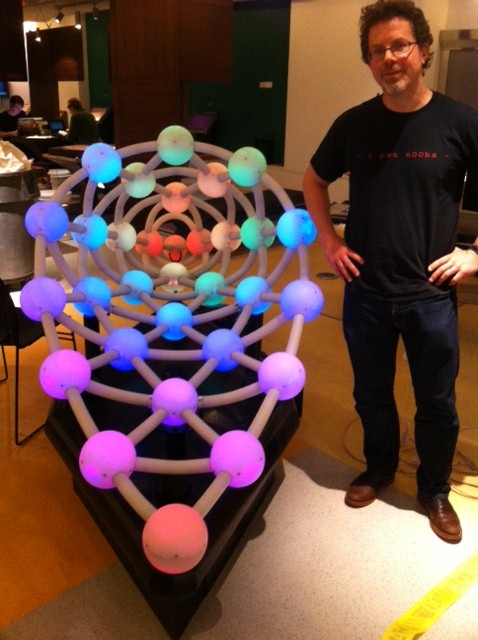

Wrap your hand around a sphere. It will light up and play a one-, two-, or three-note chord.

Think of each sphere as three people singing. They can sing all on the same note, or two on one note and one on another note, or each on a different note.

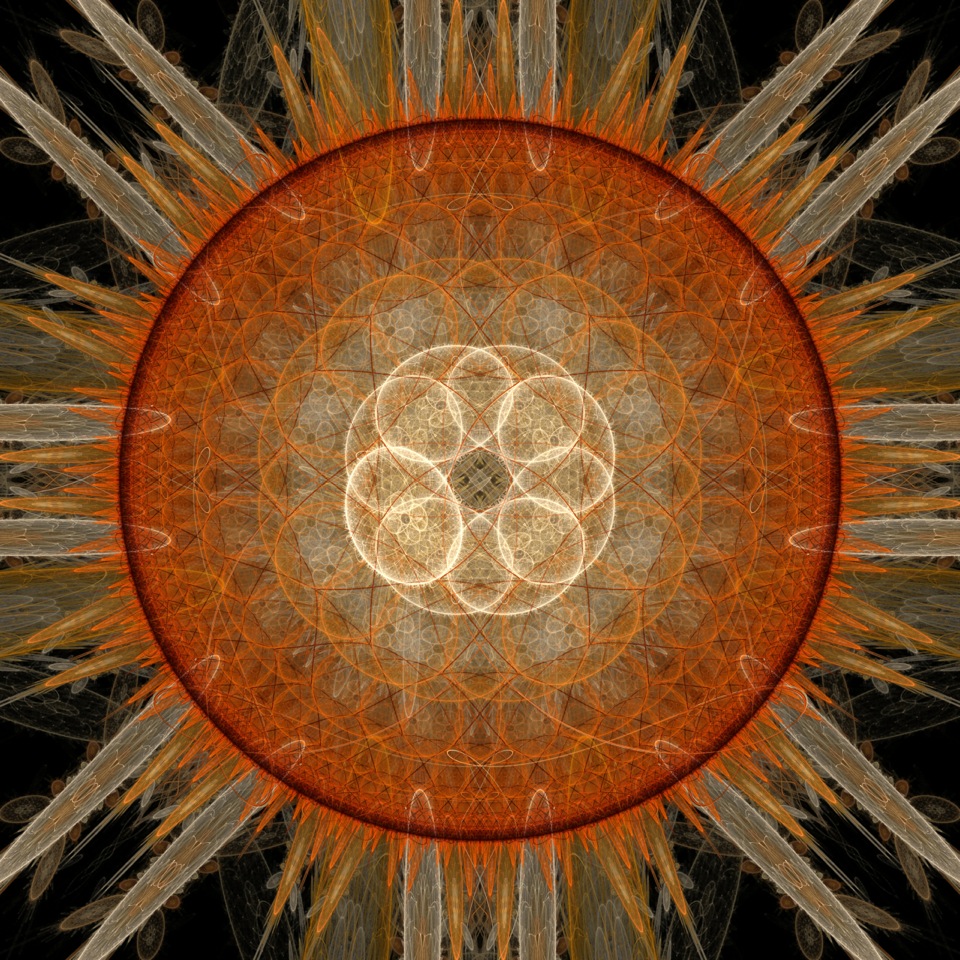

Which chords do you like? Some chords sound very weird! Try playing chords in turn in a triangle. When you arrive back at your starting sphere, the chord sounds the same, but the pitch has changed!

Have fun exploring, and visit More Math for more information about the mathematics of music.

Image courtesy of Scott Draves

Every three-note chord you could play on a piano is equivalent to some sphere in this exhibit!

Equivalent means that you should shift each individual note up or down by octaves until they are all between middle C and high C, and then shift the whole chord into the appropriate key. Among all of the equivalent chords a sphere might play, the sphere plays the one that is closest to the sphere last played.

Two connected spheres will play two notes that are the same. The third note played by both will be one half-step up or down, to make the second chord.

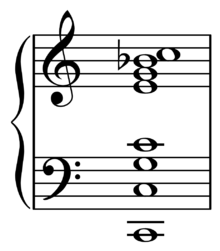

Suppose you count up the twelve-tone scale (by half steps, including all the black keys on the piano), starting with C as zero. Then C# is one, D is two, all the way up to B, which is eleven. The next note on the scale is C again, which would be twelve, but we can think of all C’s as just being “C,” so twelve is equivalent to zero. This is called counting modulo twelve (clock arithmetic), and musically it is shifting up and down by octaves.

A specific three-note chord is now a set of three whole numbers between zero and eleven. For example, the chord C-E-G is (0,4,7), and the chord C-C# is really either C-C-C# (0,0,1) or, C-C#-C# (0,1,1). The key-change equivalence is now just adding the same number, like two, to each of the numbers in a chord. So here (0,4,7) key-changes to (2,6,9) – C major to D major. Which chord the “major” sphere plays depends on what has been played before.

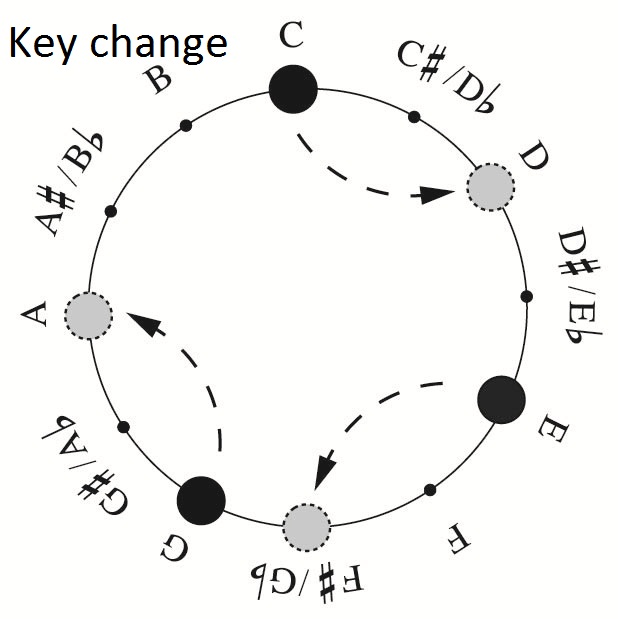

Why do some chords sound nicer than others? Music is very mathematical. A musical tone is determined by the frequency of its vibration, or how quickly it repeats itself.

Consider the lowest C in the figure. The C one octave above it has twice the frequency, or half the period. Double the frequency again and you reach middle C. Doubling again takes you to high C. But what about the numbers in between two, four, and eight? They correspond to notes that sound very harmonious with C (due to overtones).

The G below middle C is three times the frequency of that lowest C. Doubling its frequency, to six times the lowest C, takes you up an octave to the G above middle C. The multiples of five and seven give E and B flat. Also three times the frequency of F gives C, so they sound good together.

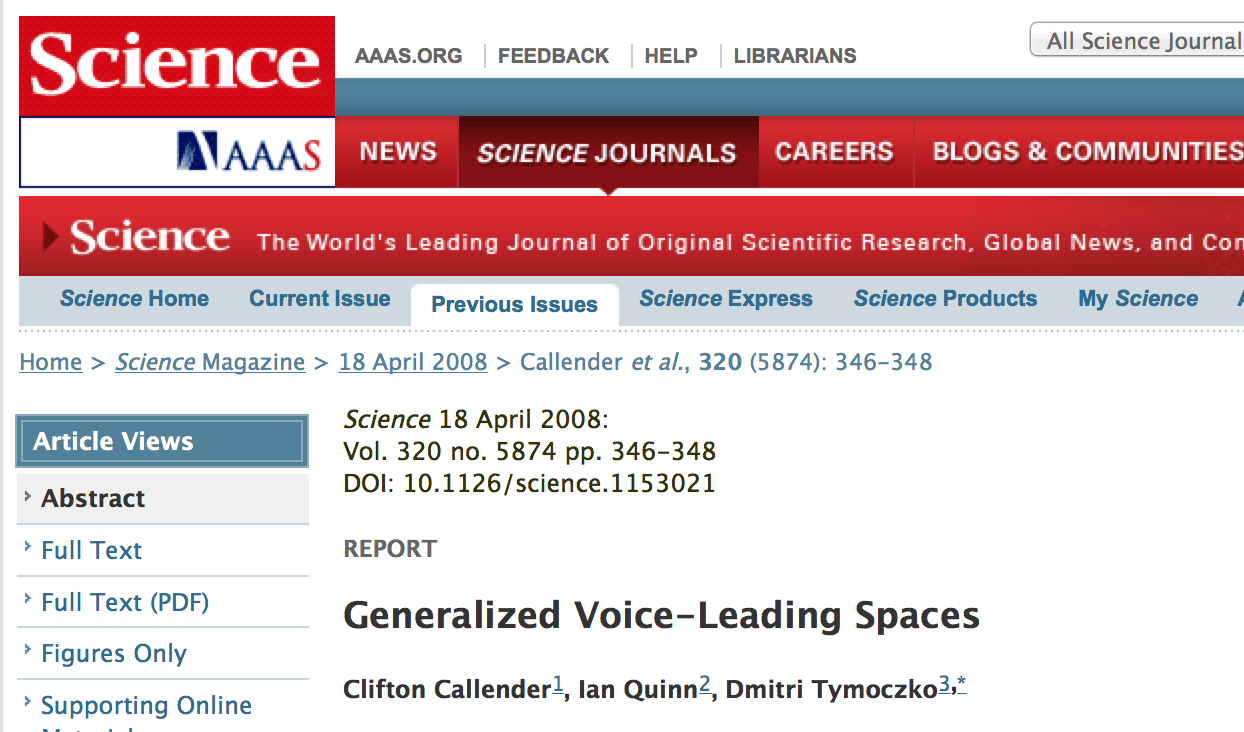

This is composer Dmitri Tymoczko, who teaches at Princeton University. He had the idea for this exhibit and designed it together with a MoMath team. The idea was based on work he did together with Ian Quinn and Clifton Callender.

Since at least the Pythagoreans, mathematicians have been exploring the harmonic (“pleasing”) structure of sound and breaking complicated waves into simpler constituent parts. This analysis took on a new life with the work of Joseph Fourier in the early 19th century, eventually leading to the modern digitization of music, sound, pictures, and video. Today, mathematicians are still very active unraveling the many theoretical mysteries that remain from these initial inquiries. One such mathematician is Professor Jill Pipher of Brown University, who also serves as the President of American Mathematical Society (2019-2021). Dr. Pipher studies interactions of harmonic/Fourier analysis with partial differential equations, as well as farther away topics such as cryptography!

The underlying research which gave rise to the idea of Harmony of the Spheres appeared in the article “Generalized Voice-Leading Spaces,” pages 346-348 of Science, Volume 320 (2008).