FEEDBACK FRACTALS

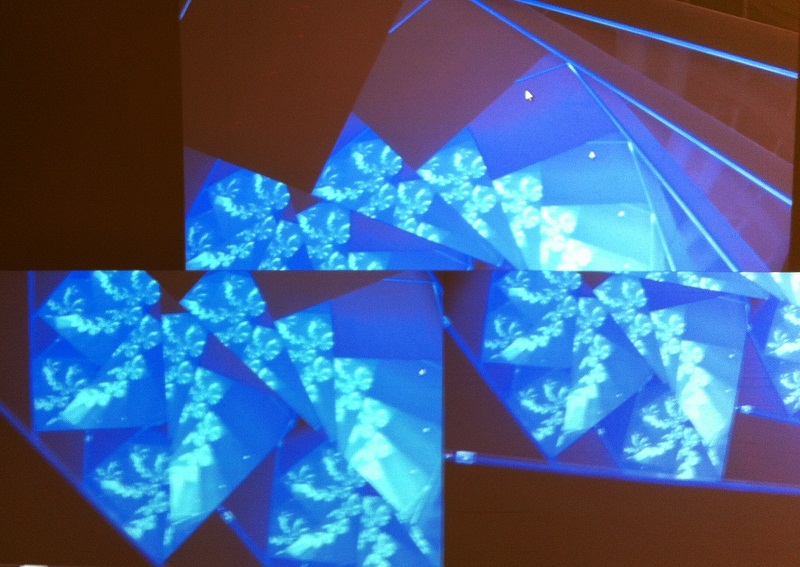

Feedback Fractals projects onto the screen what is viewed by the cameras. Point the cameras at the screen, and a smaller image of the screen is projected. Inside of that smaller image is an even smaller one, and inside the smaller image is an even smaller image, and inside that one is an even smaller one, and smaller and smaller and smaller…

You need to have all three camera operators work together, and not move the cameras too much, to get good pictures.

Fractals are objects which are not smooth or “regular.” The name, coined by Benoit Mandelbrot, comes from the phrase, “fractional dimensional.” Many fractals have what is called self-similarity. This means you can zoom in on the object and see the original shape repeated again and again.

Many real-world shapes resemble fractals much more than they resemble more regular shapes like cones, cubes, and round balls. However, they are not exactly self-similar, but have an element of randomness. It is possible to deliberately introduce such randomness into mathematically generated fractals.

There are lots of books with beautiful pictures of fractals. There are also computer programs that do electronically what these cameras do.

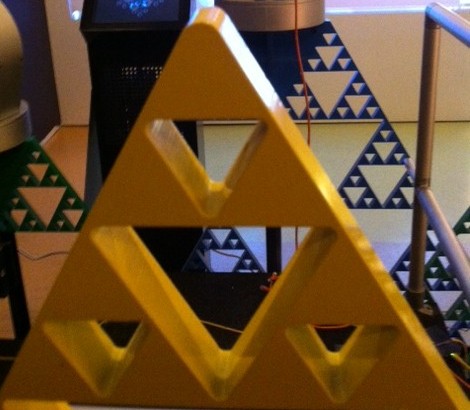

Imagine you started with one big triangle.

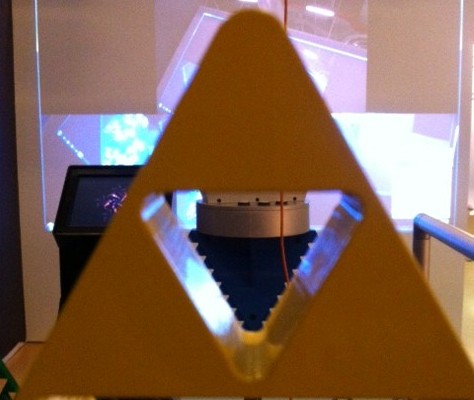

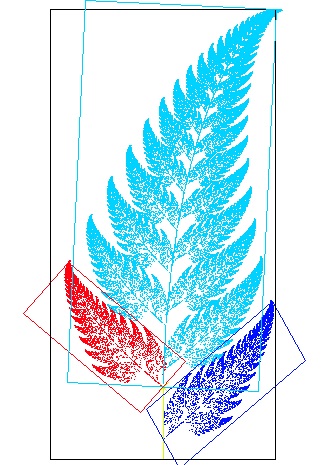

All three cameras take a picture of it. Then in place of the original triangle, each camera projects a new triangle half the size of the original. The first camera projects it in the upper part, the second in the lower left, and the third in the lower right. See image 1.

Now all three cameras take a picture of the three triangles. Then in place of that image, a new image is created by each camera projecting its image of the three triangles, decreased in size by one half, and translated. Now there are 9 small triangles on the screen. See image 2.

Each camera takes a picture of the 9 triangles. Go through the shrink-and-project procedure again and there are 27 smaller triangles on the screen.

If you go on forever, you get a mathematical fractal called the Sierpinski gasket.

Can you use Feedback Fractals to make an image like the Sierpinski gasket?

When the cameras stop moving, the display settles into a fractal, a shape that contains copies of itself. This property is called self-similarity.

The fractals you can create at Feedback Fractals are determined by the positions, angles, and zoom of the cameras. Interesting temporary images appear as things move in front of the cameras.

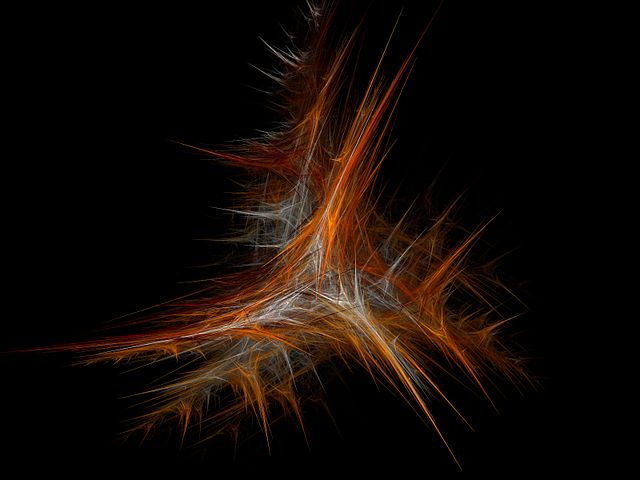

This computer generated fractal is made of up of many copies of the same shape. Just like the fractals you can make at Feedback Fractals!

Zoom in on a branch of this tree and you will see an image that looks just like the tree. Zoom in closer at a smaller branch and you’ll see an even smaller copy. Keep going and you will keep seeing the same! This tree is a fractal.

Notice that the pieces of this fern frond look just like the whole frond. In turn, each piece of those pieces looks just the the whole fern. A fractal fern!

This romanesco broccoli is a delicious example of a fractal-like shape that appears in nature. Notice how each “cone” on the broccoli is made of up a spiral of smaller cones, each one of those smaller cones is made of an even smaller spiral of cones, and so on to features too small to see.

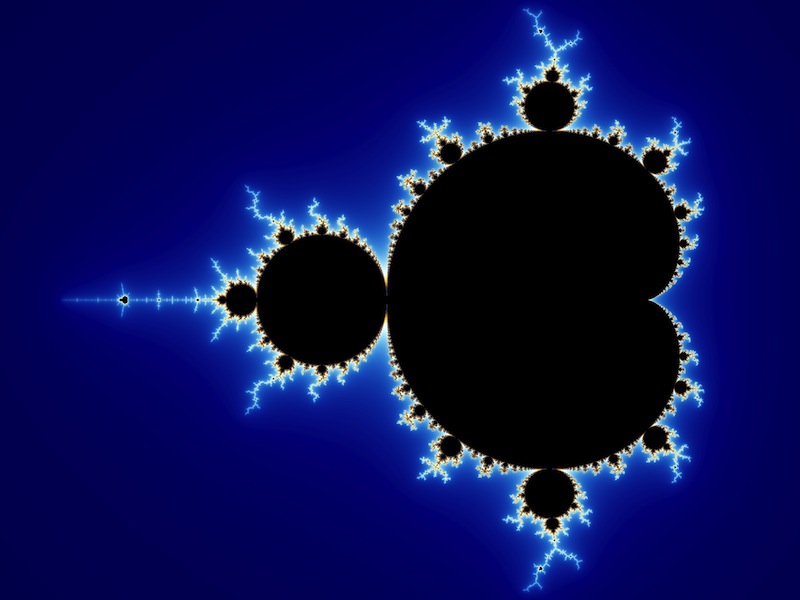

A computer generated image of the Mandelbrot set, a well known fractal and one of the first to be created with the aid of computer graphics.

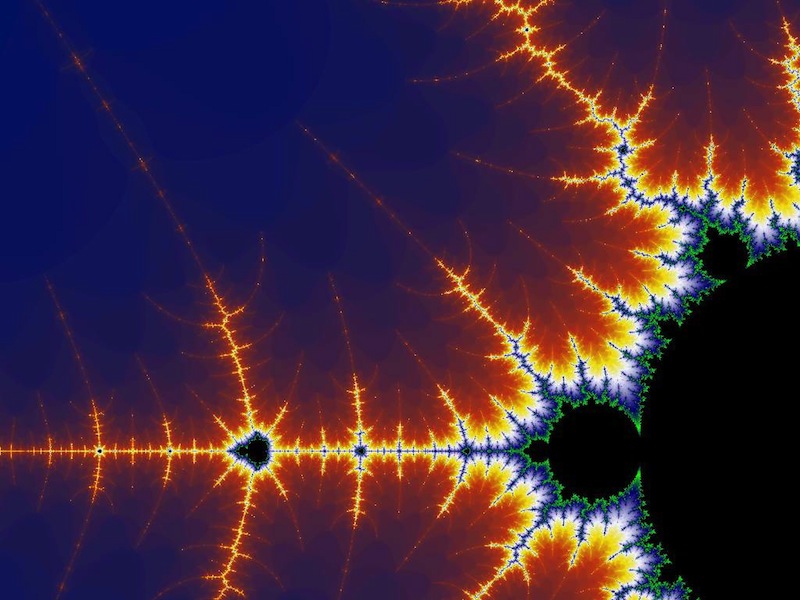

Zooming in on part of the Mandelbrot set shows how its shape is actually made up of many smaller copies of itself. This is what self-similarity of a fractal refers to.

The Gibbons-Scattone Family

The Gibbons-Scattone Family provided support that made Feedback Fractals possible.

Michael BarnsleyMathematics

Michael Barnsley is a professor of mathematics at Australian National University and the author of SuperFractals. Professor Barnsley’s research has advanced mathematical discovery in fields related to Feedback Fractals.

Bob DevaneyMathematics

Bob Devaney is a professor of mathematics at Boston University. Devaney has provided valuable insight into mathematical fields related to Feedback Fractals.

Sarah KochMathematics

Though some fractals can be traced back to Leibniz more than 300 years ago, their serious study by mathematicians is considerably more recent. Sarah Koch, a Thurnau Professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is an expert in, among other things, complex dynamics. At a basic level, this means applying some nice polynomial function over and over again on the complex plane, and trying to understand the limiting behavior. Before going to Michigan, Dr. Koch was a postdoc at Harvard; she also received a prestigious Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship. In addition to her teaching and research, Professor Koch is the Director of the Math Corps at U(M), a math outreach program for middle schoolers and high school mentors.

Benoît Mandelbrot1924-2010Mathematics

Using access to IBM’s computers, Mandelbrot was one of the first to use computer graphics to create and display fractal geometric images, leading to his discovering the Mandelbrot set in 1979. He showed how complexity can be created from simple rules, and things considered chaotic or a mess, such as clouds in reality had a ‘degree of order.’

His research contributed to the fields of geology, medicine, cosmology, engineering and the social sciences. Science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clark called the Mandelbrot set ‘one of the most astonishing discoveries in the entire history of mathematics.’”