The Coaster Rollers sled rolls smoothly on the rollers even when they turn in various directions. You wouldn’t be surprised at that if the roller were balls (spheres) since you are used to things rolling on balls. But the rollers are nothing like balls; they have a shape rather like an acorn and when you look at them you wouldn’t guess that they would give a smooth ride.

Now look at the shape of the sled. It fits neatly between the side rails and spins around in any direction, but again its shape is not round as you might expect but like a rounded triangle. In fact, the shape of the sled is exactly that of a cross-section of one of the rollers.

These shapes share with circles and spheres the property of being of constant width in two or three dimensions.

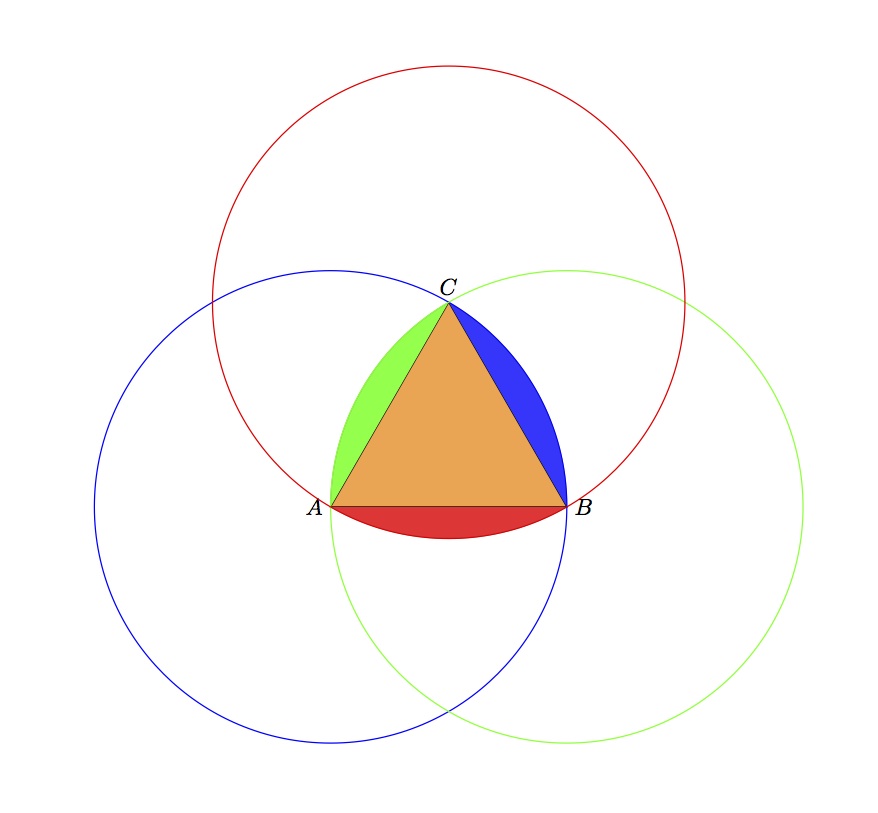

The shape of the sled is called a Reuleaux triangle, named after a 19th Century German engineer. It can be drawn as in the image at the right: start with an equilateral triangle (orange) and around each of the vertices A, B and C draw a circle passing through the other two vertices. Add on to the triangle the blue, green and red crescents. Do you see why the shape now has constant width? This allows the sled to turn in its track staying in contact with the sides.

The rollers are now constructed by rotating this figure around one of the axes — say the vertical line through C. That makes it have constant width in every direction so that two flat surfaces with these shapes between them are always the same distance apart and therefore slide smoothly over each other.

How do the shapes in Coster Rollers relate to those of the Square-wheeled Trike next to it? That exhibit is also about shapes riding smoothly on each other; there both the shape of the roller (wheel) and the shape of floor are changed from the usual, here the floor stays flat and the rollers have a different shape. What would happen if we made a tricycle with wheels in the shape of Reuleaux triangles? Would it ride smoothly on a flat floor?

The answer is contained in the image to the right. Even though the “wheel” is of constant width so its top edge would stay a constant distance off the floor, the tricycle would be connected to it somewhere in the middle on an axle. Unfortunately, unlike a round wheel, there isn’t any “middle” point that is the same distance from the edge in every direction. With a circular wheel, this middle point is fixed and is where you would want to place your axle. As a Reuleaux triangular wheel rotates, however, the axle would need to change positions along the curve shown in the image to the right to ensure a smooth ride.

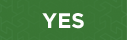

Actually, a Chinese man, Guan Baihua, did build a bicycle with Reuleaux wheels, but to make it work the connection of the axle to the wheel had to be more complicated. And the front wheel was a Reuleaux pentagon as in the image. That can be constructed from an ordinary pentagon in the same way by drawing circles around the vertices. The link shows some photos.

In the same way one can construct Reuleaux polygons with any odd number of edges.

Reuleaux polygons have many practical uses: for non-circular coins that work well in vending machines, for manhole covers, and even for a drill that bores out an (almost) square hole (see the Gallery).

A Bermudian dollar in the shape of a Reuleaux triangle.

A British fifty pence coin is a Reuleaux heptagon.

A Reuleaux nonagon coin minted in Austria.

The Canadian “Loonie” dollar coin is an eleven sided Reuleaux polygon.

A Reuleaux triangle-shaped window at Notre Dame cathedral in Bruges, Belgium.

Since circular disks have constant width, a circular manhole with a cover of slightly larger radius has a nice property: no matter how you position the lid, you will not be able to drop it through the hole. The Reuleaux triangle also has constant width, so a Reuleaux-triangular manhole with a slightly larger Reuleaux-triangular lid would work just as well! Pictured is such a valve cover in San Francisco.

French mathematician Sophie Germain (1776 – 1831) would have enjoyed a ride on solids of constant diameter, but instead of studying these, she won the grand prize from the Paris Academy for her work about elastic surfaces, in addition to making considerable progress in attacking Fermat’s Last Theorem.

Thomas Lachand-Robert was the director of the Laboratoire de Mathematiques at the Universite de Savoie, in Chambery, France. He studied objects of constant width, like those used in Coaster Rollers.

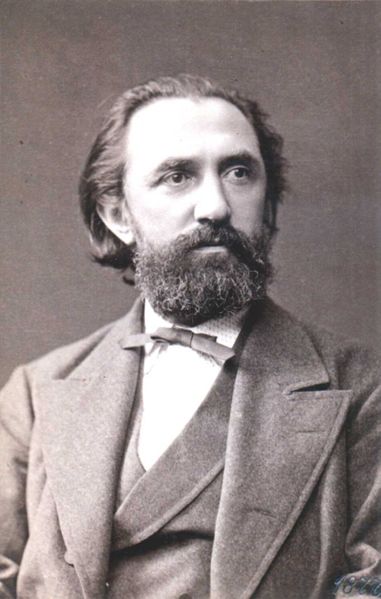

Franz Reuleaux [1829-1905] was a German engineer-scientist who studied kinematics: the ways that mechanical parts move with each other. He developed a symbolic notation to describe the topology of mechanical connections, and used it to classify the ways that machines translate one kind of motion into another.

He is most famous today for the Reuleaux triangle, one of the simplest shapes of constant width. The base of the sled in Coaster Rollers is in the shape of a Reuleaux triangle!