BEAVER RUN

As you watch the beavers scurry around the tracks at Beaver Run, turn the dials to change the tracks in real time. Those poor beavers are getting so turned around! You can make them run in circles, isolate them from each other, start an epic chase, or trap them far away from their home — but can you ever make them crash into each other? Give it your best shot and then read the discussion in More Math.

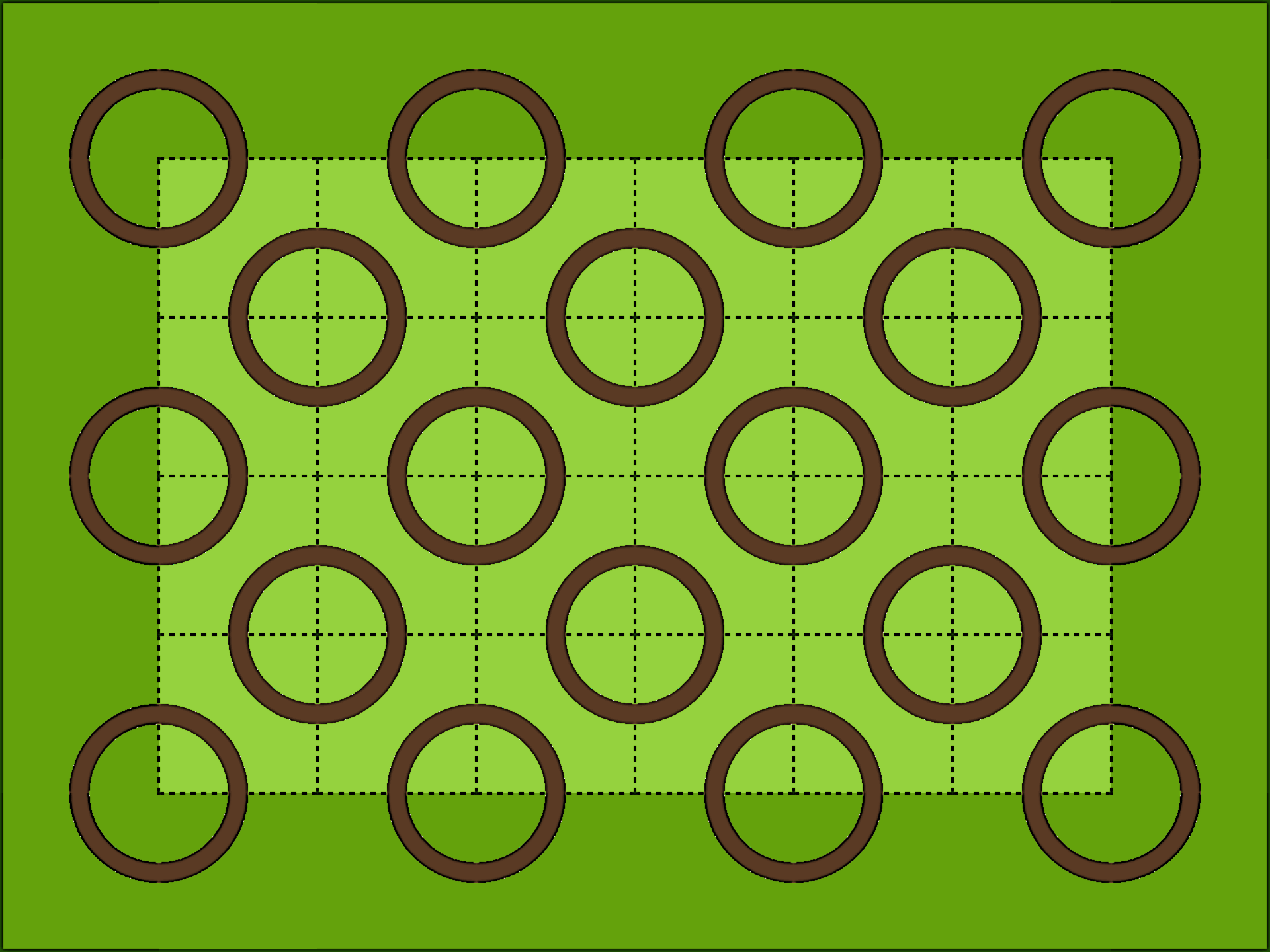

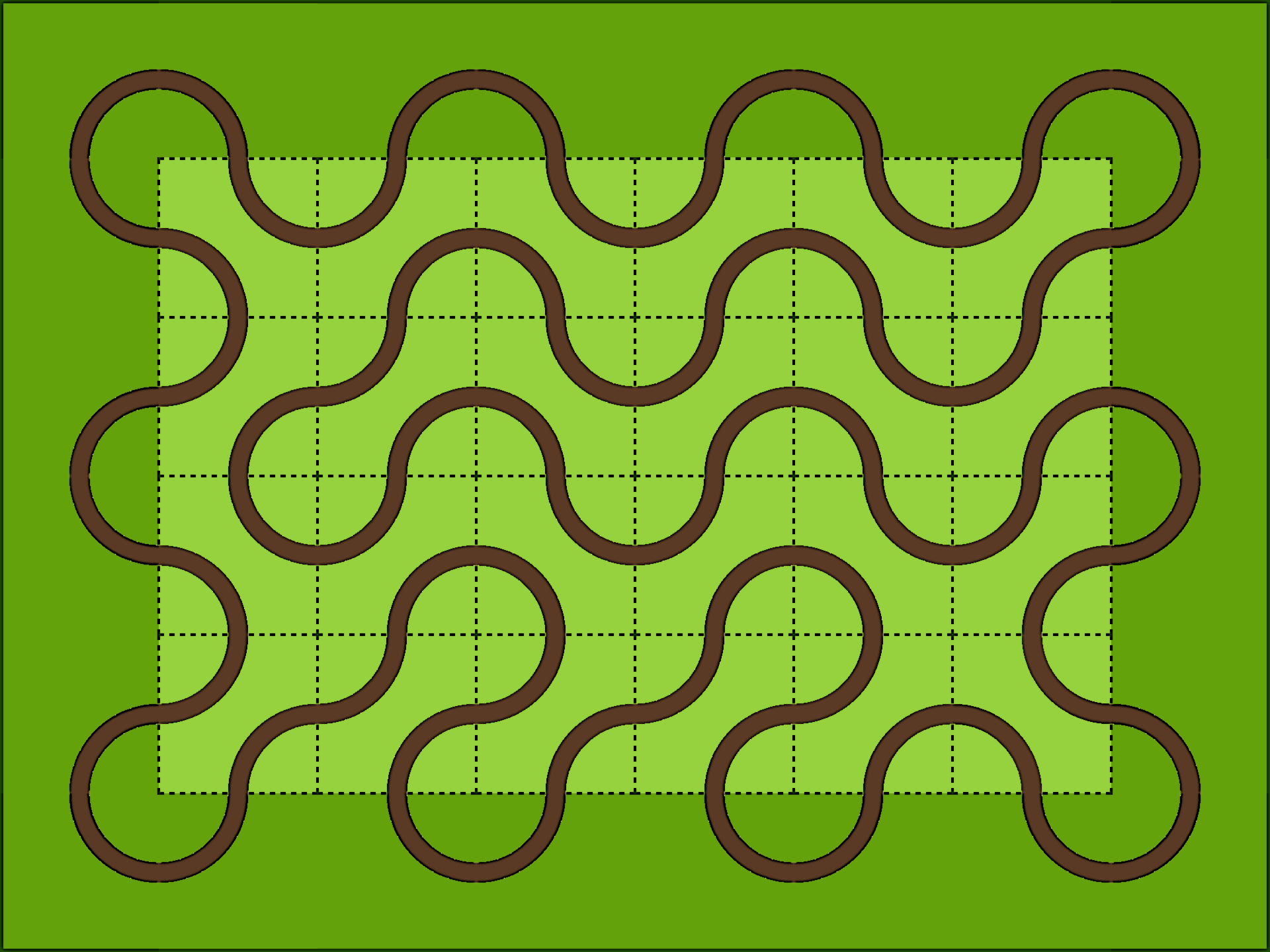

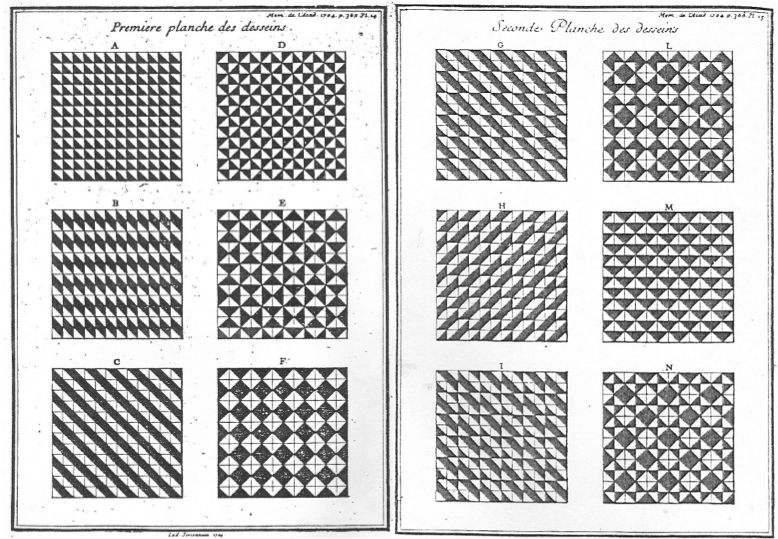

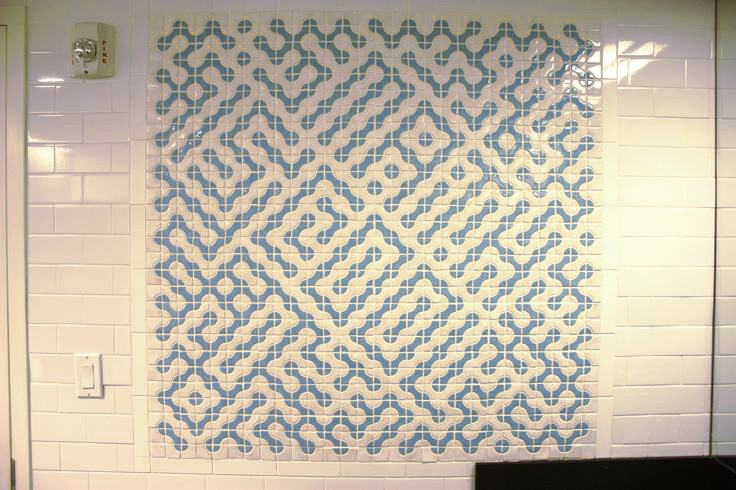

Do you notice anything odd about the shape of the Beaver Run tracks? They’re based on Truchet tiles! The Truchet tiles behind the tracks at this exhibit, introduced by Cyril Stanley Smith, feature two quarter circles. Two small tiles are pictured to the right, but one is just what you get when you rotate the other. Can you see the way to put these two tiles together to make the three patterns below them? The triangle-patterned tiles pictured below were the original tiles studied by Sébastien Truchet. If you find yourself in the restroom, make sure to look closely at the walls — you just might recognize some Truchet tiles!

At the heart of this exhibit lurks an impossibility proof. To give you a sense for how those go, consider the classic puzzle of tiling an 8×8 checkerboard with dominoes. The task is so easy, you might accidentally come up with a solution! (One solution is given to the right.)

To make things more interesting, suppose now that we cut two corners from the board. As pictured, there are two ways to do this: we could cut two corners from the same side or we could cut diagonal corners. Can you see a way to tile each of these boards with 2×1 dominoes?

You probably found a solution to the first board pretty quickly. One possible solution is to the right, but there are many ways to do it.

On the other hand, you were probably stumped by the second board. One near-solution is presented to the right. While your near-solution might look different from this, chances are they share one frustrating property — two of the squares are not covered! Each domino covers two squares, so it seems like we should have the right tool for the job, but we just can’t seem to cover that board. This could mean one of two things: (1) There’s a way to do it, but we haven’t stumbled upon it yet, or (2) What we’re trying to do is impossible. If we claim it’s impossible and then our friend manages to do it, we’d feel pretty silly. How do we convince ourselves beyond all doubt that it can’t be done?

Let’s count the squares on our cornerless boards. For the board we were able to tile, you should count 31 light, 31 dark. For the board that gave us trouble, you should count 32 light, 30 dark.

When we place a domino, can it cover two light squares? Two dark squares? A light and a dark? Convince yourself that it must cover one of each. This means that on the board that gave us trouble, no matter where you place your first domino, the count will then be 31 light, 29 dark. After a second domino, the count will be 30 light, 28 dark. How must this end? Eventually we’ll have only 2 light and 0 dark. Our failed attempt left two light squares uncovered and now we can explain why there were two and why they were light!

This problem would be trickier if the board hadn’t been colored to begin with, but we could have been the ones to color it. One of the things mathematicians do is look for hidden structures that help us see why things are true.

Now that we have a sense for the flavor of an impossibility proof, let’s prove that the beavers can never crash! Before we get started, we should ask what it would mean for the beavers to crash. For example, if the two beavers are moving at the same speed, could one crash into the other from behind? (No, because how would they catch up to each other if they’re going the same speed?) So when we talk about crashes, we’re talking about head-on collisions.

This means we need a way to talk about directions on our track. This is a little tough, since the tracks can change at the turn of a dial! To get your bearings, first verify that you can do two things: (1) You can turn the dials so that the tracks are 18 small circles, and (2) You can turn the dials so the tracks form one big loop. There is only one way to make the circles, but one of the many ways to make a loop is pictured to the right.

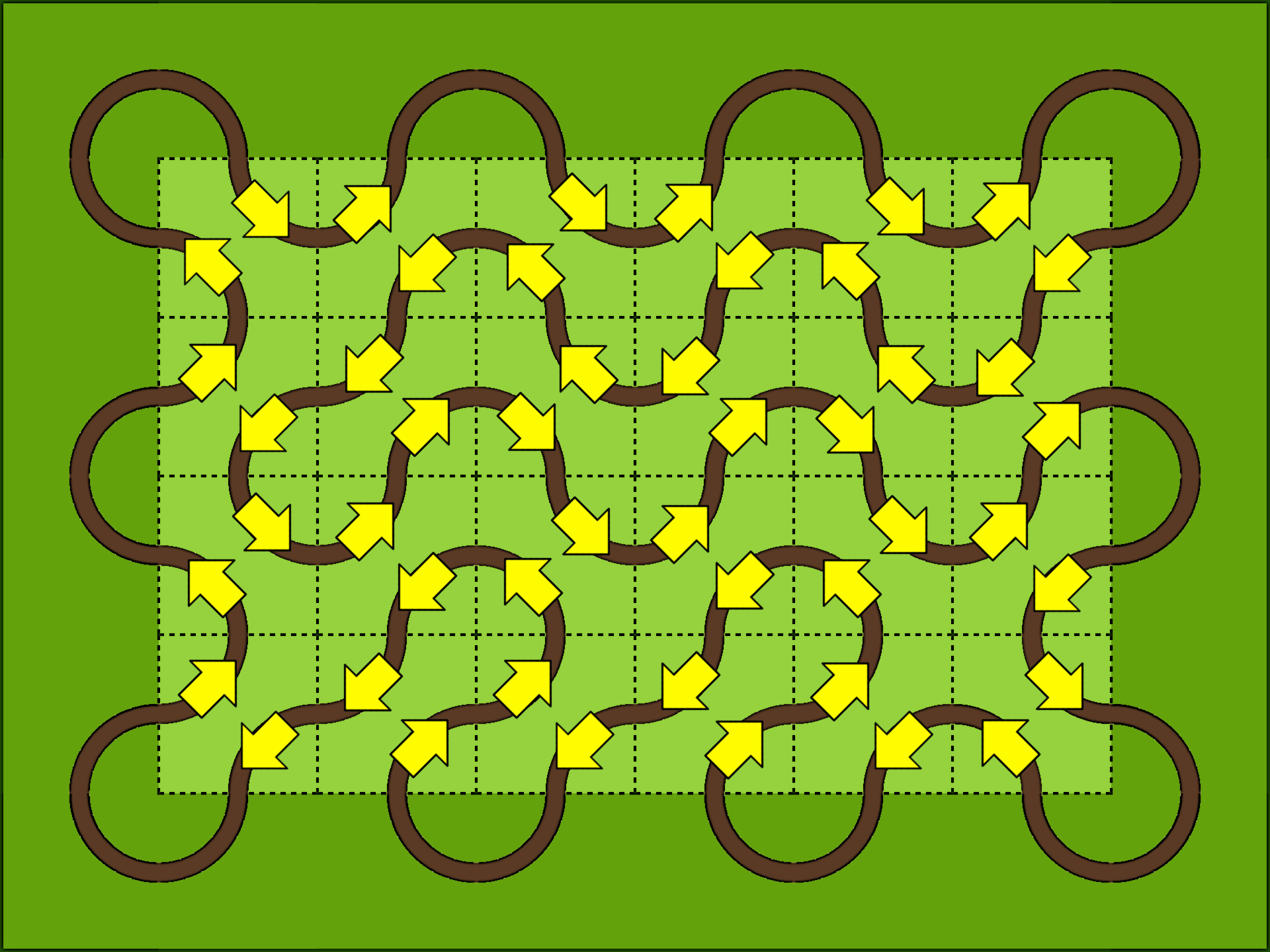

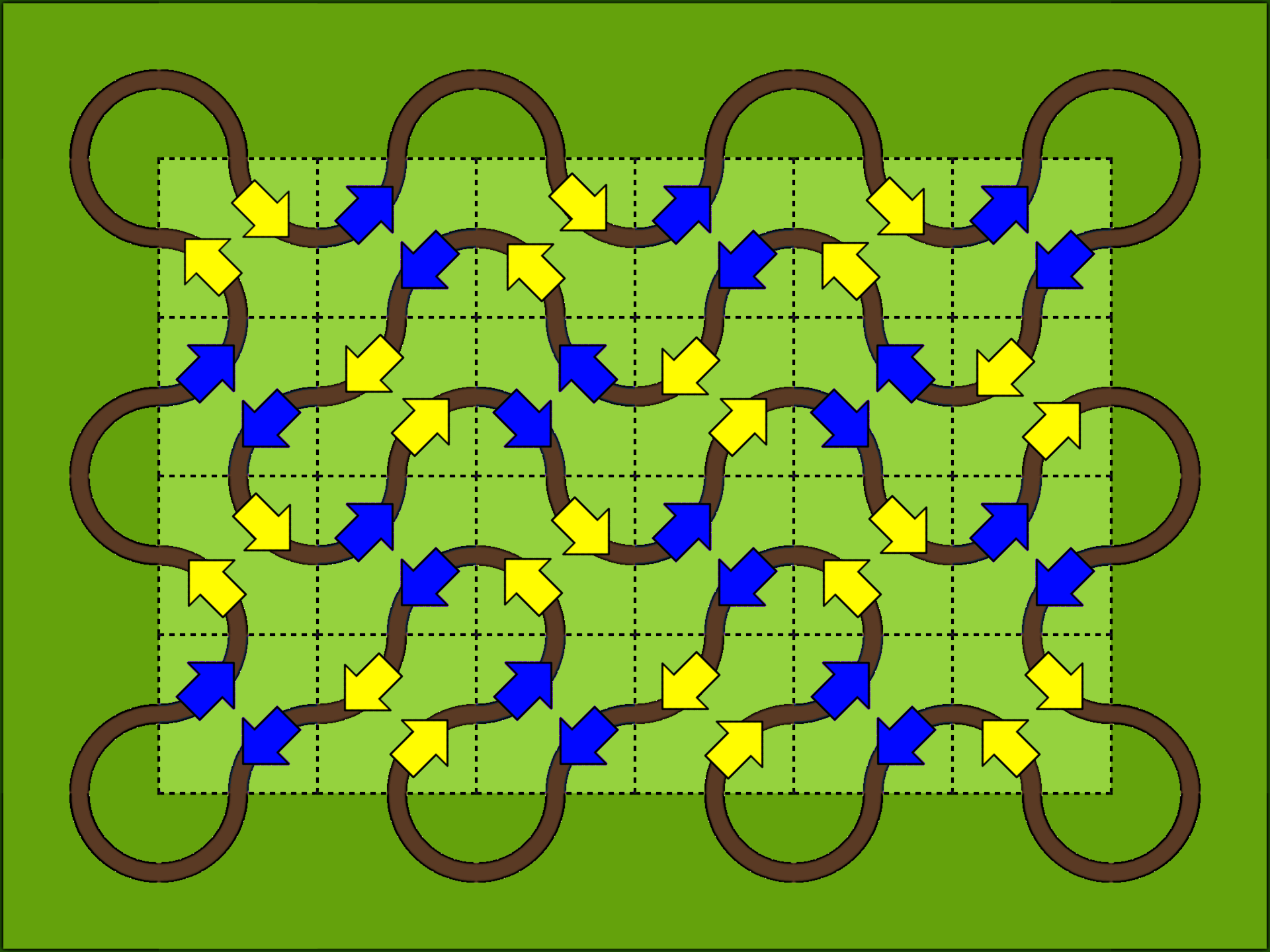

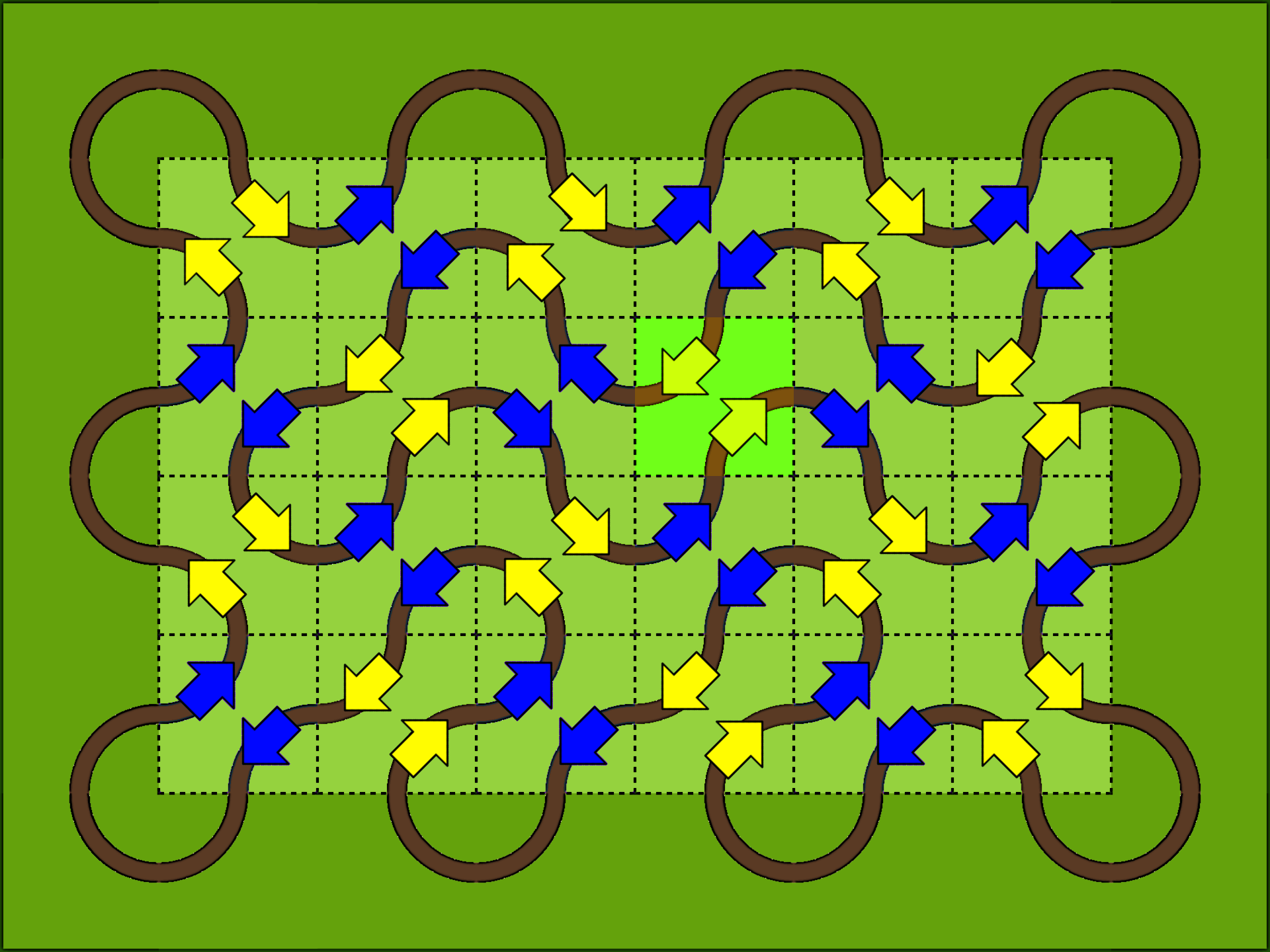

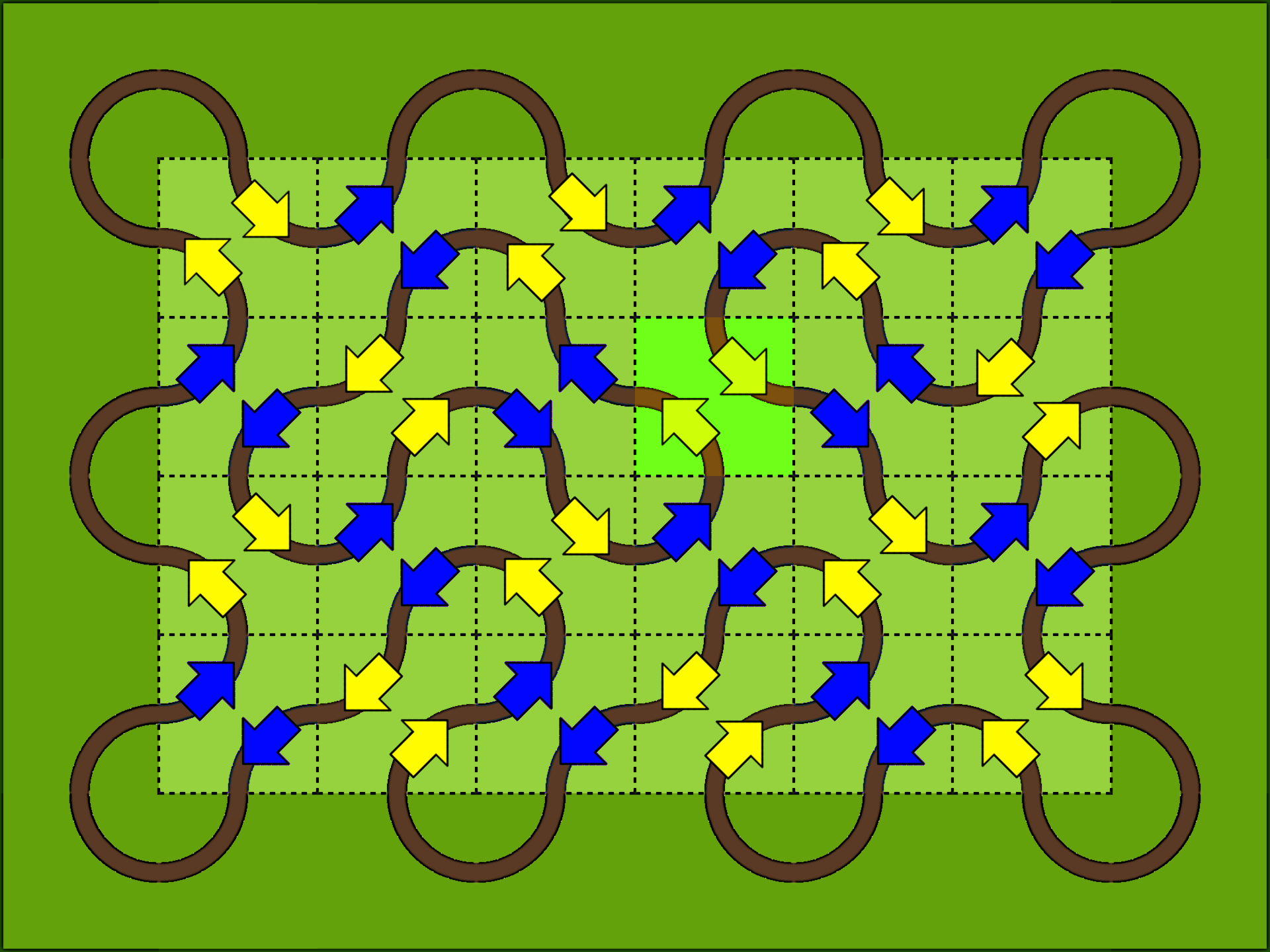

When we have a bunch of small loops, we would have to consider two different directions for each loop. With one big loop, there are only two directions to travel, so it’s much easier to start here. Pick a direction to travel around your loop and label each track segment with an arrow as you get to it, indicating which way you were moving. To the right is a labeling for our example.

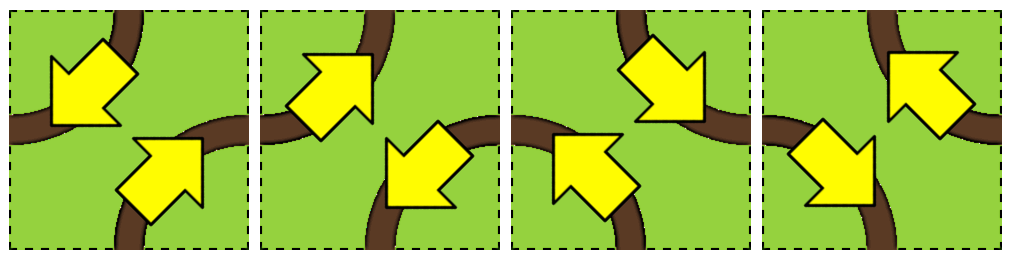

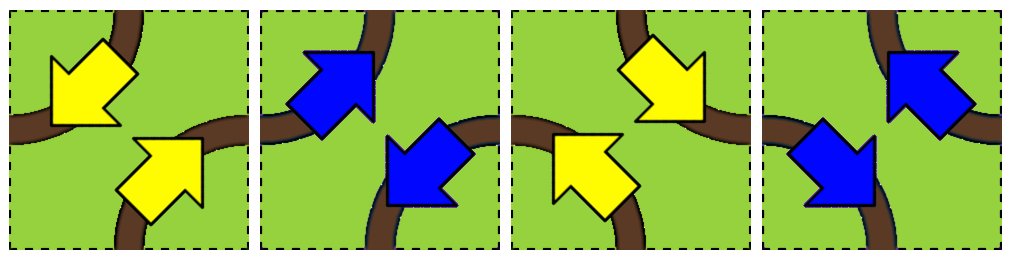

One thing that might leap out at you is that on any given tile (representing a turntable), the two arrows point in opposite directions. While it’s not yet clear why that’s happening, it happened for our example and it happens for any big loop. This means there are only four different types of tiles, pictured to the right.

On two of the tiles, the beavers enter through the top or bottom and leave through a side, while on the other two tiles, the beavers enter through a side and leave through the top or bottom. Let’s color that last type blue, as in the picture to the right. If we go back through our track and update arrows so they’re blue or yellow, accordingly, something remarkable happens: a checkerboard pattern emerges! But why? (Hint: If a beaver leaves through the bottom of a tile, must it enter or leave through the top of the next tile?)

Let’s take a look at a random yellow tile. What happens if we rotate it? Assuming our beavers aren’t on it when we rotate it, its arrows would update to the directions they would travel if they were to eventually come across it. Since all of its neighbors are blue, to be able to enter and leave this tile from a blue tile, its arrows would again have to be yellow. This means that it stays yellow after rotation — it just happens to be the other yellow tile type. Can you see that blue tiles would similarly become blue tiles when we rotate them?

Even though we now have two loops in our track, each has a safe direction of travel tied to the other. As long as we never turn a tile that a beaver is on, we can always update the arrows so that there are no head-on collisions, no matter how many dials we turn!

The only trick is to make sure we start both beavers off with the same orientation. Did you notice how both beavers started on the same tile, on opposite sides of their dam? Were they pointing in the same direction or in opposite directions? (Hint: Which one would make it so they never crash?)

Artwork from Truchet’s original work.

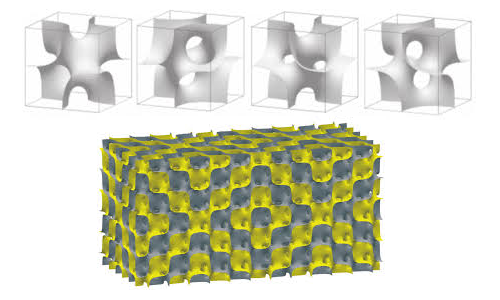

Just as you can tile in 2D, you can fill space in 3D! Here are the four different orientations of a 3D Truchet tile and one possible pattern you can form as you tile space with them.

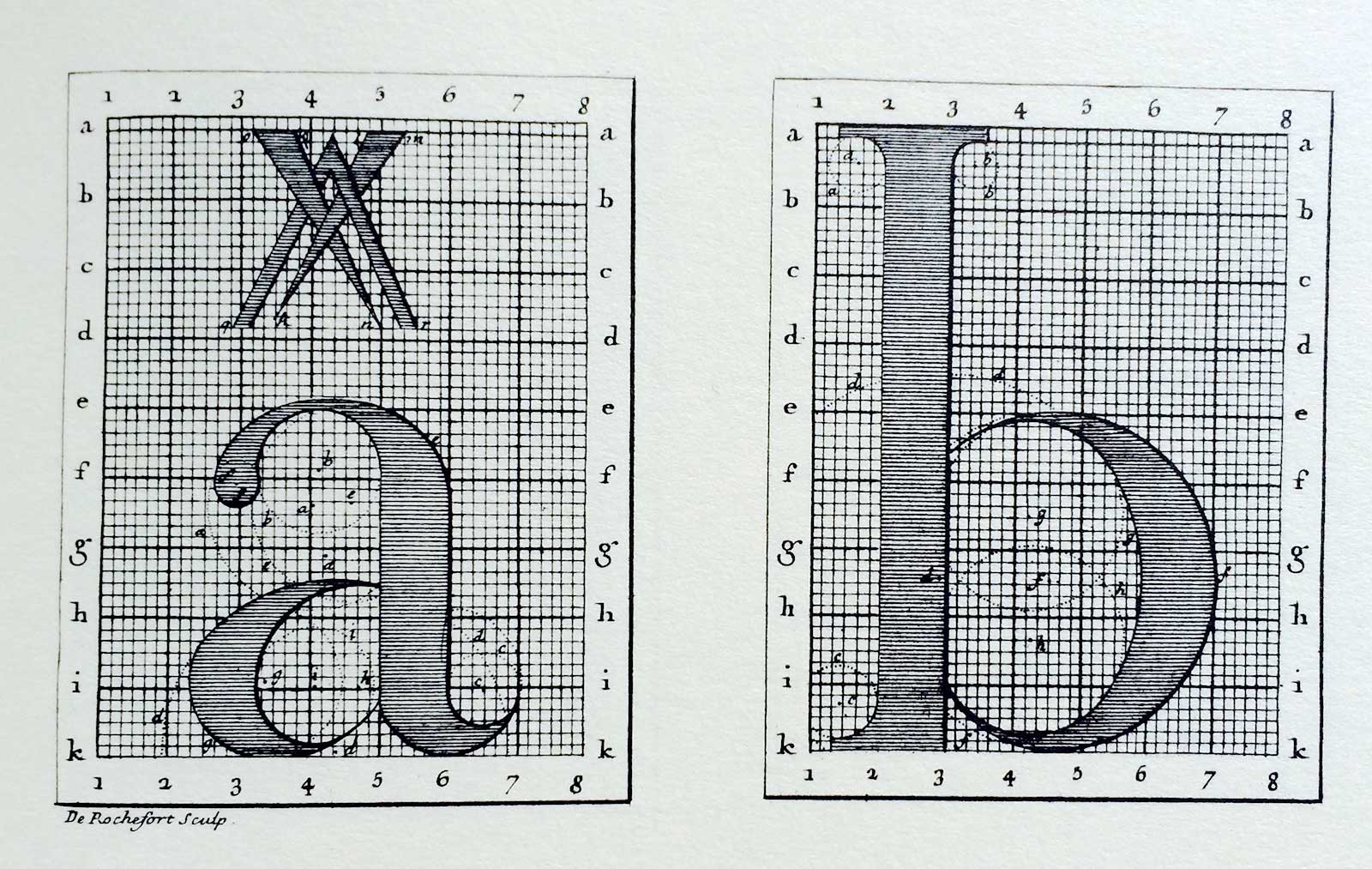

Romain du Roi, the first Modern typeface, was designed by Sébastien Truchet. Perhaps you’ve spotted the common thread of pixelation between his work with type points and tiles.

There are messages hidden in the Truchet tiles in the MoMath restrooms — a different message on each floor!

Sébastien Truchet1657-1729Priest, Mathematician, Engineer, Typographer

Father Sébastien Truchet was a priest, mathematician, engineer, and inventor. Perhaps most famously, Truchet was a member of the Bignon Commission along with Jacques Jaugeon, the royal typographer to Louis XIV. The Bignon Commission’s goal was to assess the feasibility of the project that would become “Descriptions of the Arts and Trades,” a 113 volume work covering French handcraft and manufacturing processes. Their first inquiry was into typography, which led them to create first typographic point system. They also developed the notions of bitmaps, vector fonts, and italicization as a transformation. The font they created, Romain du Roi, is considered the first Modern typeface and was widely imitated throughout Europe. Since Truchet designed the letters for Romain du Roi on a grid, many consider it one of the first “digital” fonts. You might see some parallels between designing typography in a grid of pixels and orienting Truchet tiles to make patterns.

Cyril Stanley Smith1903-1992Metallurgist, Historian of Science

After earning his Sc.D. at MIT, Cyril Stanley Smith started his career in 1927 as a metallurgist at the American Brass Company, studying copper alloys for their mechanical, magnetic, and conductive properties. After leaving ABC in 1942, he served on the War Metallurgy Committee, worked on the Manhattan Project, founded and directed the Institute for the Study of Metals at the University of Chicago, and held a dual appointment at MIT in the Departments of Humanities and Metallurgy.

He won many awards, including the Presidential Medal for Merit (1946), the Francis J. Clamer Medal of the Franklin Institute (1952), the Pfizer Medal from the History of Science Society (1961), the Gold Medal of the American Society of Metals (1961), the Douglas Medal from the AIME (1963), the Leonardo da Vinci Medal from the Society for the History of Technology (1966), the Platinum Medal of the Institute of Metals (1970), and the Gemant Award from the American Institute of Physics for “pioneering the use of solid state physics in the study of ancient art and artifacts to reconstruct their cultural, historical and technological significance” (1991).

In the course of Smith’s study of metallurgy, he used Truchet tilings to better understand crystals. He wrote the article, “The Tiling Patterns of Sebastien Truchet and the Topology of Structural Hierarchy” in 1987, which included the tile featured here at Beaver Run.

Google, Inc.

Google, Inc. provided support that helped make Beaver Run possible.