Have you ever wanted to send someone a message that nobody else could read? During times of war, the military often wants to send messages that the enemy cannot read, and one way to do so was to use the M-209 machine.

Try using this machine to turn your own messages into code!

“DBO ZPV CSFBL UIF DPEF?”

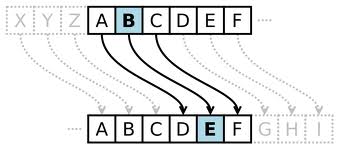

The Caesar cipher was one of the earliest ways to encode a secret message. To use this method, first write out the 26 letters of the alphabet. Then, “shift” the letters and write the alphabet below:

Normal Alphabet: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Letters to use in Code: B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A

Now you can write your message in code. Instead of using the normal alphabet, however, replace each letter that you would normally use with the letter below it. If you wanted to write an A, you would look it up in the chart in the top row, then write the letter below it, a B. If you wanted to write the word “CAN”, for example, it would be written as DBO. Then send your message.

Try writing your own secret message!

When your friend gets your message, he or she can figure out what it means by looking up each coded letter in the bottom row, then replacing it with the letter above it. If you sent your friend the message “DBO”, he or she would look up the D in the bottom row, then replace it with the C directly above it. Your friend would also replace the B with an A and the O with an N, and would then figure out that you wrote “CAN”.

Try using this information to figure out what the message at the beginning of this page means!

This code can be made more complicated by “shifting” the bottom row more than one time. Can you think of any way to make the code more difficult to solve? What if you removed spaces? What if you dropped vowels?

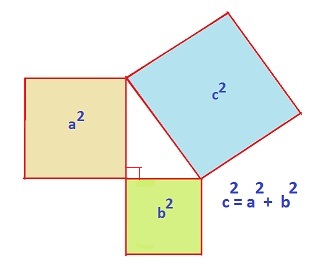

Laurent de la Hyre’s 1649 painting, “Allegory of Geometry,” shows a young woman who embodies geometry. The upper left corner of the sheet she is holding contains a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem. Hyre thus highlights how central the theorem is to geometry.

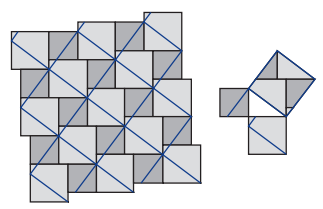

“Street Musicians at the Doorway of a House” is an oil painting from the mid 17th century. The tiling pattern on the floor might look simple, but but when overlaid by another grid, the floor shows a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem discovered by Annairizi of Arabia in the 10th century. This floor pattern is thus known as “The Pythagorean Tiling.”

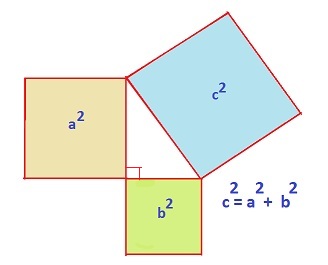

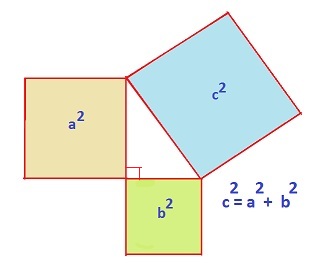

The above is a picture of Annairizi of Arabia’s tiling proof of the Pythagorean Theorem. Notice that if you remove the grid consisting of blue lines, you yield the Pythagorean Tiling highlighted in the previous painting. Can you see how this demonstrates the theorem? See More Math for more on picture proofs.

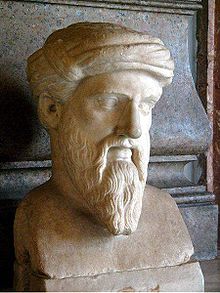

Much legend surrounds Pythagoras, pictured above, and the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras was born around 570 BCE in the Greek town of Samos. More information about Pythagoras, and the legends that surround him, can be found in the section on The Pythagorean Theorem.

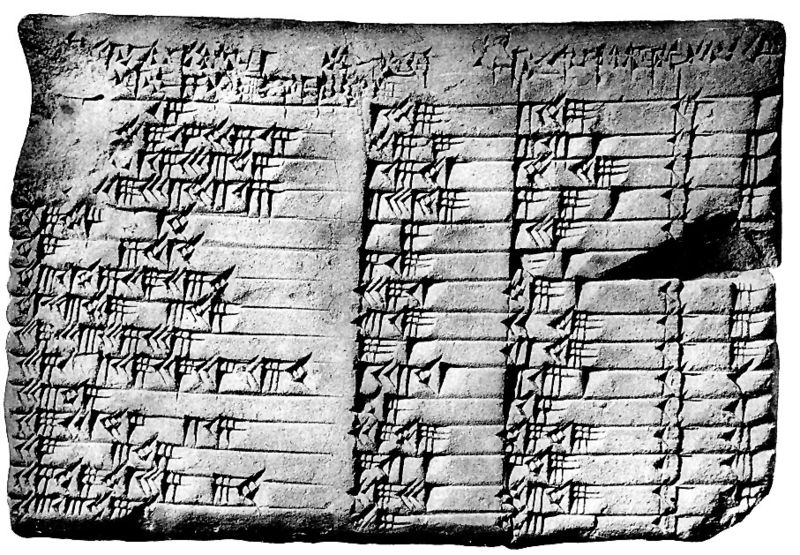

Shown above is Plimpton 322, a clay tablet from Babylonia written between 2000 and 1500 BCE. This tablet provides strong evidence indicating that the Babylonians knew The Pythagorean Theorem: the tablet lists many Pythagorean Triplets which would have been difficult to discover without knowledge of the Theorem.

National Grid provided support that made Time Tables possible.

Britain’s Kathleen Ollerenshaw (1912 – 2014) was both a mathematician and a politician. She completed her doctorate at Oxford in 1945 while raising her two young children, as her husband was posted abroad for front-line war service. She also served as president of the UK’s Institute of Mathematics and its Applications, one of the UK’s two learned societies for mathematics (the other being the London Mathematical Society).

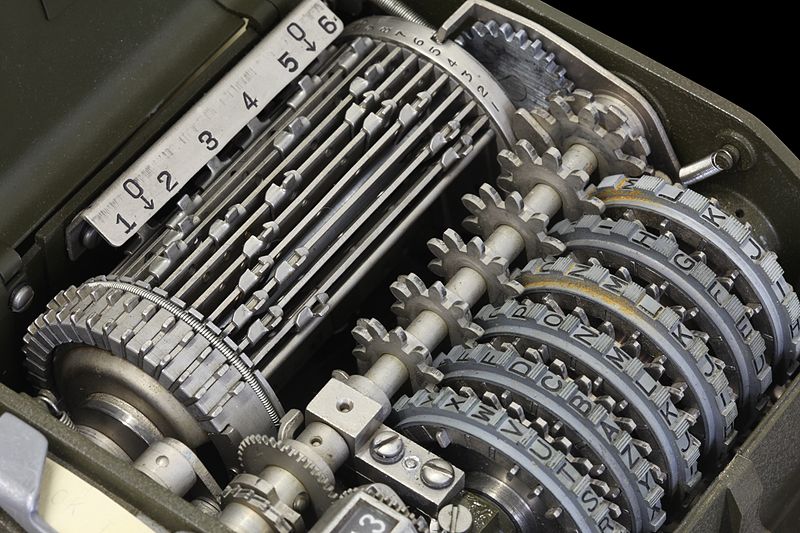

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons (Sim0n)

The National Cryptological Museum provided the M-209 machine on loan for use in this exhibit.

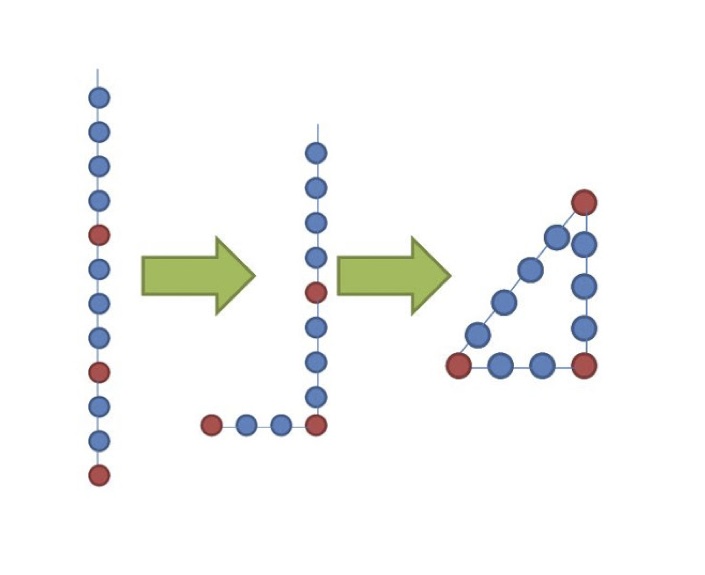

Andrew Wiles is famous for proving Fermat’s Last Theorem: consider finding solutions to the equation an+bn=cn where a, b and c are integers. When n equals 2, this is the Pythagorean Theorem, and infinitely many integer solutions exist. Fermat, in 1637, conjectured that for n greater than 2, no such solutions exist. While Fermat claimed to have had a proof, he said it was too big to write in his margin. Wiles famously proved the theorem in 1995 after devoting seven years of his life to finding a proof. His proof was 100 pages – certainly too big for Fermat’s margin!

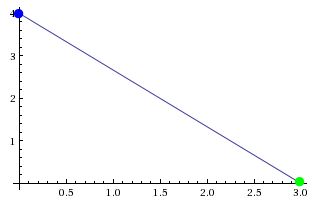

You might have been told that “the shortest distance between two points is a line.” That is certainly true, but how can we find the distance between two points? Say, for example, that you wanted to find the distance between the points (0, 4) and (3, 0) as shown to the right.

One cool solution is to use the Pythagorean Theorem and build a right triangle. With this situation, for example, you have one side be the vertical line from (0, 0) to (0, 4), the second side be the line from (0, 0) to (3, 0), and the hypotenuse is then the line connecting the two point. In our case, our sides have length 4 and 3. To figure out the distance between the two points, use the Pythagorean theorem to find the hypotenuse!

The M-209 Encryption Machine was used by the US military in World War II and the Korean War. When used by the Navy, it was designated as the CSP-1500. The M-209 was favored by the military as it was small and lightweight, ideal for a mobile force.

The M-209 has six adjustable key wheels. To encipher a message, the operator sets the wheels to a random sequence of letters. The indicator disk, on the left side, is turned to the first letter in the message that the operator wishes to encrypt. A power handle on the right side is turned and the encoded letter is printed onto a paper tape. Once this is printed, the key wheels all advance one letter in the alphabet. Then, the operator repeats the process with all remaining letters in the message.

When the operator needs to indicate a space between words, the letter “Z” is used. Context enables the individual reading the message to determine when the letter “Z” was used as the letter itself rather than a space.

Once the message is enciphered, it can be sent to a recieving party, often via Morse code. The recieving party must also know which six wheels were used to encipher the message.

The M-209 operated on a variation of a reciprocal subsitution cipher, reversing the order of the alphabet. Thus, an A would be encoded as a Z, a B would become a Y, a C would become the letter X, and so on. Once the letters are substituted in this way, they are shifted to the left. The amount of the shift to the left is determined by the letter on the key wheel, a variation of the Cesearian cipher. Then, to add extra security, the key wheels advance once after each letter is encrypted. Thus, the cipher becomes more complicated. A code with the wheels set to AAAAAA would activate the pins PONMLK. This combination of ciphers created an enciphered message that would have been reasonably challenging but not impossible for the enemy to track. Therefore, the US military used the M-209 for routine, tactical transmissions.