There is an invisible object hovering over the pedestal! Grab the handles of the display and move it around and through the invisible object to see its cross sections. If you lose the object by moving the display too far, remember that it is centered above the pedestal.

Which of the three objects on the display screen is it? How can you tell?

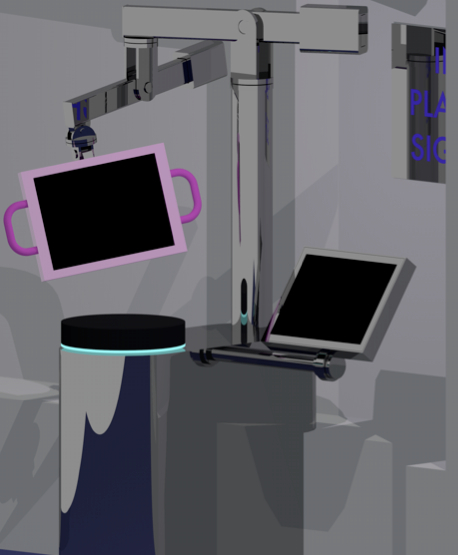

Trying to figure out what a shape looks like by looking at pictures of it from different angles is interesting enough to have motivated some cool pieces of modern art. On the right are two views of a piece by sculptor Markus Raetz.

Are “YES” and “NO” actually cross sections of this? If you look closely at the lower image, you’ll see that there isn’t a slice you could make to get “NO,” but if you shined a light, you could get “NO” as a shadow on the wall. These shadows are called projections, in which you see all the cross sections from one angle together in a single image.

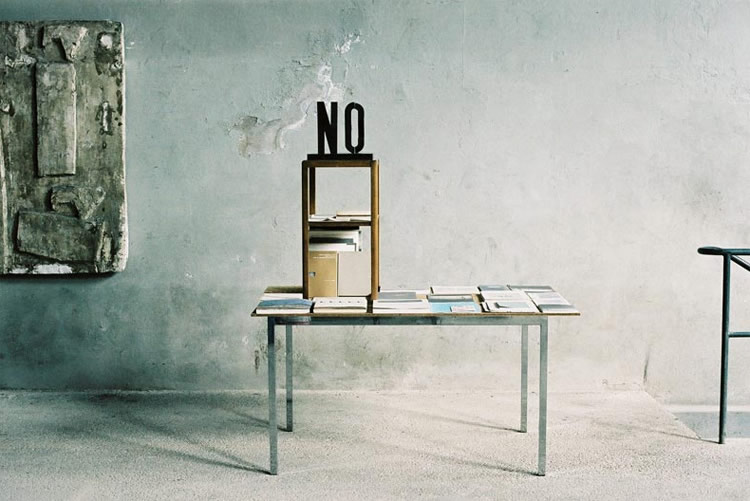

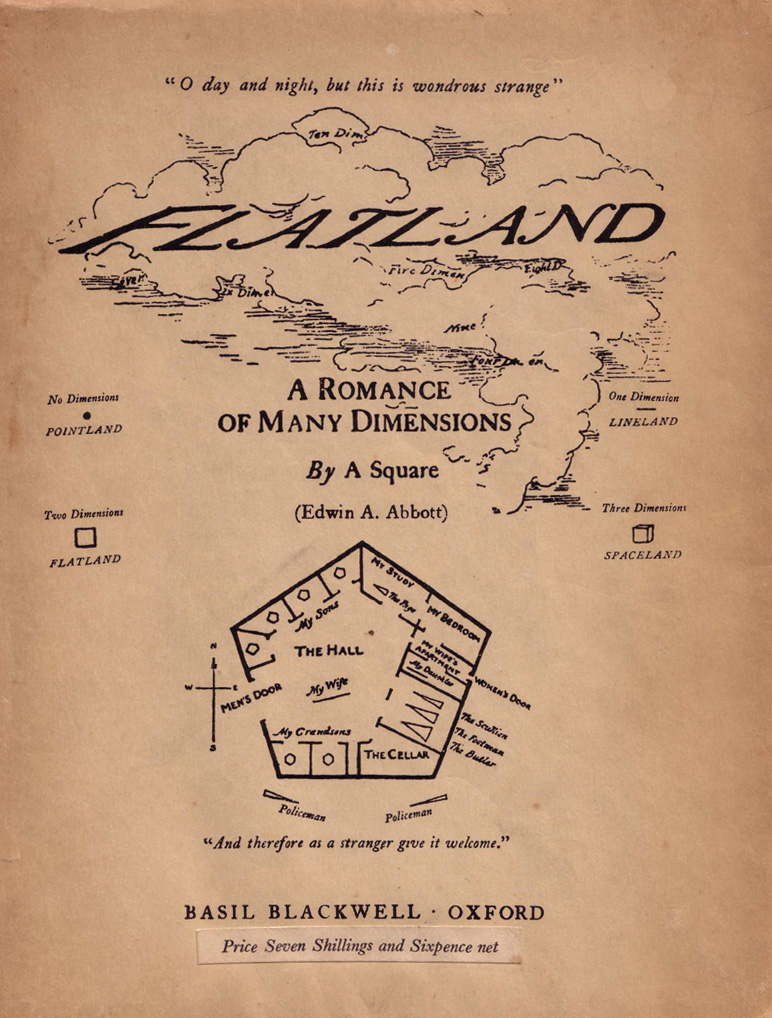

In Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, Edwin Abbott Abbott explores a society that exists in a two-dimensional world. The creatures that inhabit this world are line segments and polygons. One day, A Square meets A Sphere, but since they meet in Flatland, A Square is only able to see cross sections of A Sphere. Having explored the 2D cross sections of different objects, you might now have a good sense for the circles that A Square saw when A Sphere popped into his world!

If a four-dimensional object were to interact with our three-dimensional world, what would you see? What would happen if a tesseract were to pay us a visit? Just like a cube has squares as its cross-sections, you might see a bunch of cubes as the cross sections of a tesseract. On the other hand, In Plane Sight shows that the angle you scan an object from changes the cross sections you see. How else might a tesseract look as it passes through our world?

If the invisible object were a bagel, you might see it as a bunch of bagel washers of various sizes.

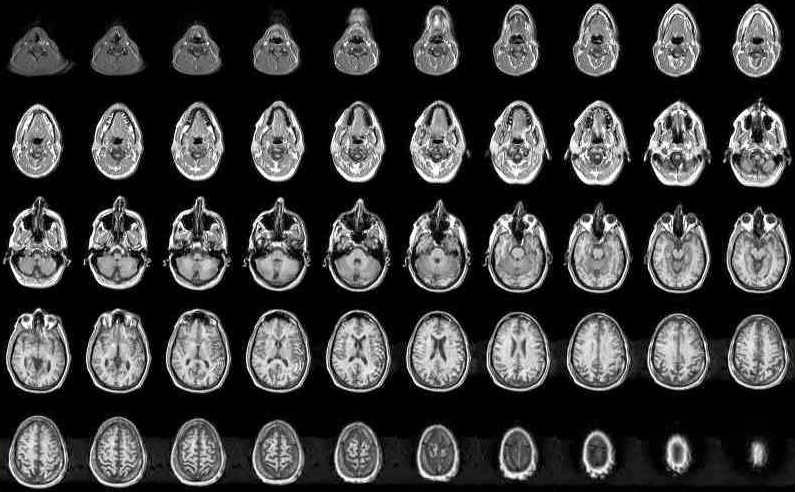

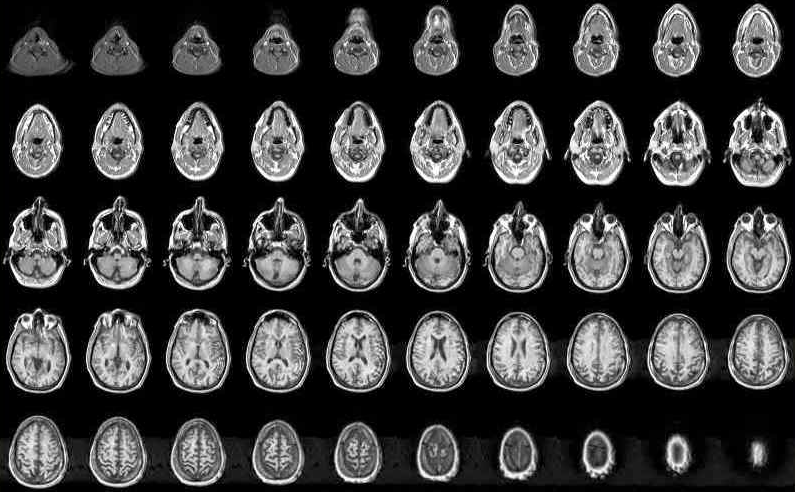

If the invisible object were a human head, the device might see this sequence of images.

Edwin Abbott Abbott was an English schoolmaster and theologian. Abbott was a well-regarded author, publishing many works on religion, writing, and Francis Bacon. His most famous work, however was Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a novella he published under the pseudonym A Square.

Reconstructing an invisible solid from knowledge of its cross-sections is not so far from the use of wavelets to, for example, reconstruct an image from its compression in a format like JPEG. A pioneer in these disciplines is Belgian-born mathematician Ingrid Daubechies (b. 1954), who taught at Princeton for many years before moving to Duke in 2011. Among her very many accolades are a MacArthur “Genius” award, the Leroy Steele Prize, and her service as president of the International Mathematical Union (the organization which, among other things, organizes the Congresses where Fields Medals are awarded).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) views a living human body as a series of slices, just like the slices in a loaf of bread. Each scan produces an image of the cross section of the body along one plane, just like the plates in this exhibit. In order to understand the three-dimensional structure within the body, a large collection of slices must be collected and linked together. This can be done either by a computer, or by a skilled doctor using exactly the same kind of thinking as in this exhibit. Pictured are MRI scans of a human brain. If the invisible object were a human head, this series of images is what you would get if you started the device at the neck and pulled it up to the top of the head, aiming straight down.

Edwin Abbott Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions was written in 1884. Since it is now in the public domain, there are many ways to find and read it online! Here is one link:

https://archive.org/details/flatlandromanceo00abbouoft