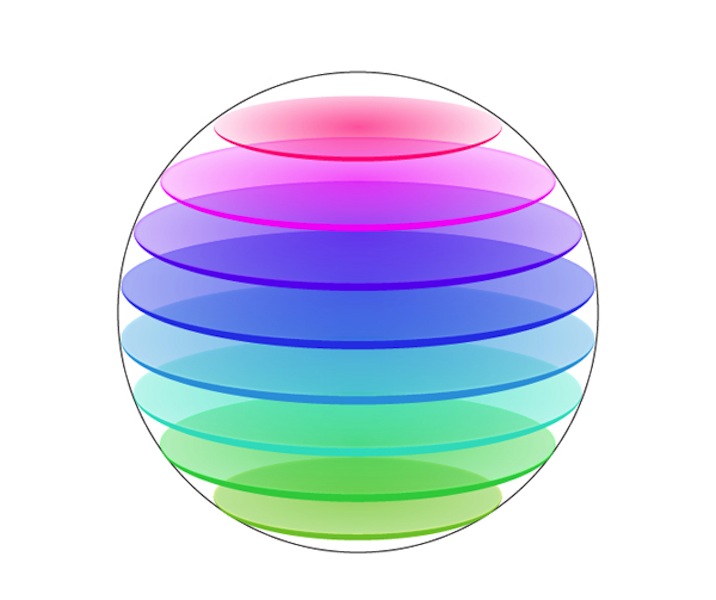

This exhibit is the reverse of Wall of Fire. There you can see the shapes of slices, or cross sections, of solid objects. Here, you stack up slices drawn on plates to sketch out a solid shape!

Can you stack the plates with circles to make a ball? Can you use each of the other sets to make a cube?

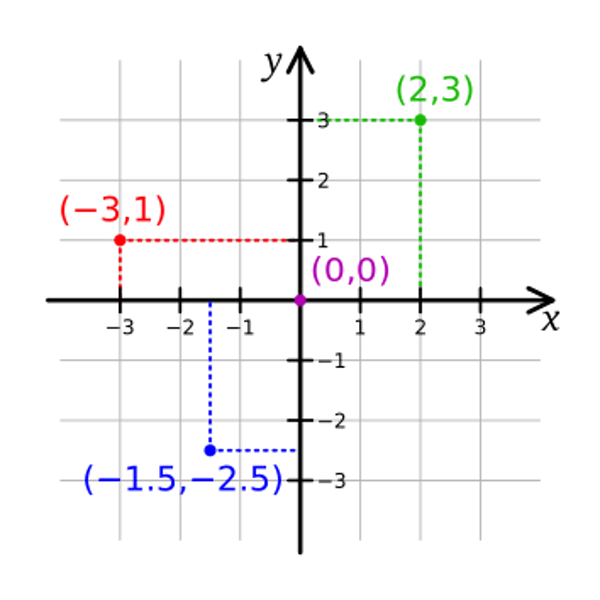

What do we mean when we say dimension?

If you were standing on a line segment and wanted to tell someone where on the segment you were, you could tell her how far you were from an end point. That’s only one number, or one piece of information. Because you only need one piece of information to specify your location on a line segment, we say that a line segment is one-dimensional.

If you were standing in a square room and you wanted to tell someone where you were, you would need to give two pieces of information. For example, you could tell her how far you are from the eastern wall and then how far you are from the northern wall. No matter how you do it, you will need at least two numbers, so a square is two-dimensional.

One way to think about the dimension of an object is to consider the smallest number of pieces of information you need to tell someone an exact location inside that object. Can you think of why a point is zero-dimensional?

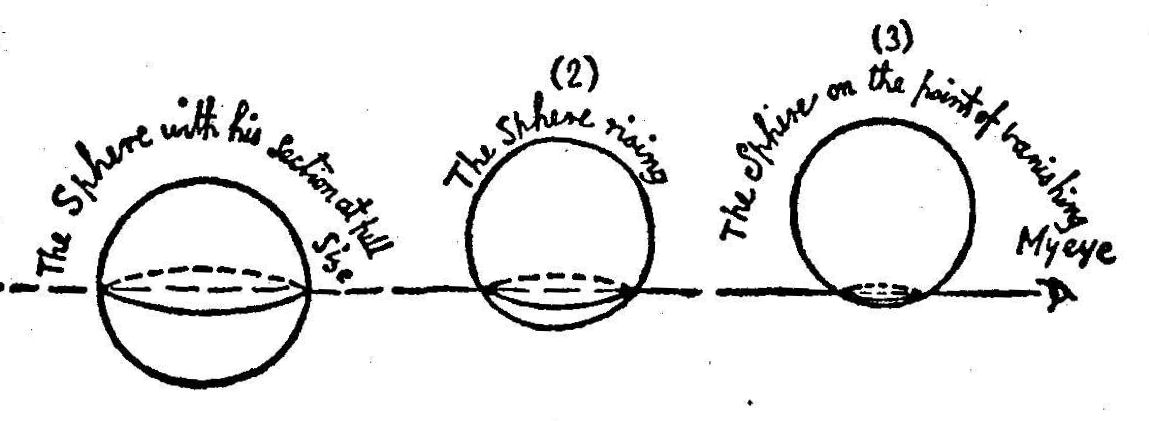

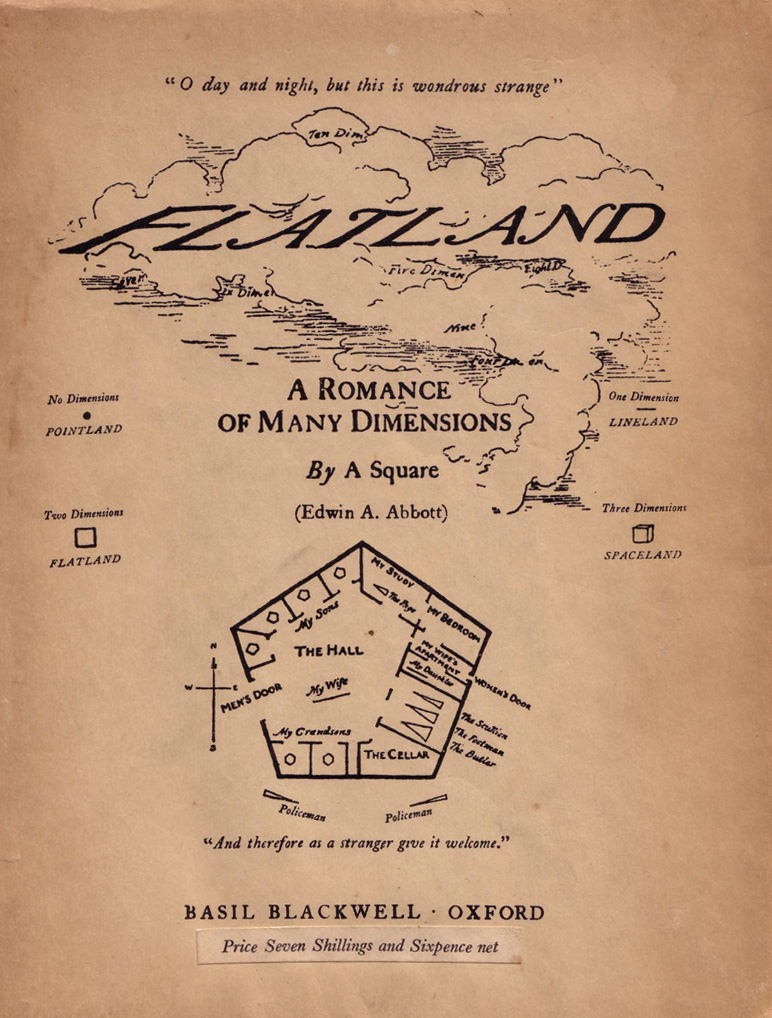

In Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, Edwin Abbott Abbott explores a society that exists in a two-dimensional world. The creatures that inhabit this world are line segments and polygons. One day, A Square meets A Sphere, but since they meet in Flatland, A Square is only able to see cross sections of A Sphere. Having constructed a sphere out of circular cross sections, you might now have a good sense for the circles that A Square saw when A Sphere popped into his world!

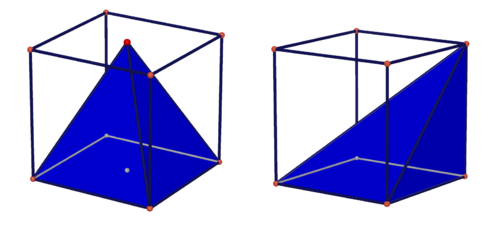

If a four-dimensional object were to interact with our three-dimensional world, what would you see? What would happen if a tesseract were to pay us a visit? Just like a cube has squares as its cross-sections, you might see a bunch of cubes as the cross sections of a tesseract. On the other hand, 3-D Doodle also gives you a way to build a cube from other sorts of cross sections. How else might a tesseract look as it passes through our world?

3-D Doodle shows how you can make higher dimensional objects from lower dimensional ones. To make a 3-dimensional object using 3-D Doodle, you need to draw many 2-D shapes and stack them in a new direction: up.

Maybe you can think of how you could use 3-dimensional shapes to make a 4-dimensional shape, much like 3-D Doodle. You need a new direction. It might be time, if you played a sequence of 3-D images, or you might try to picture a fourth spatial dimension. The figure at right is one attempt to show a tesseract, a 4-D cube, which you can think of making by stacking 3-D cube slices in four-dimensional space!

Suppose you took the circular cross sections and stacked them into a sphere. If the radius of the biggest disk is R, then you might recall that the volume of the sphere you’ve constructed is

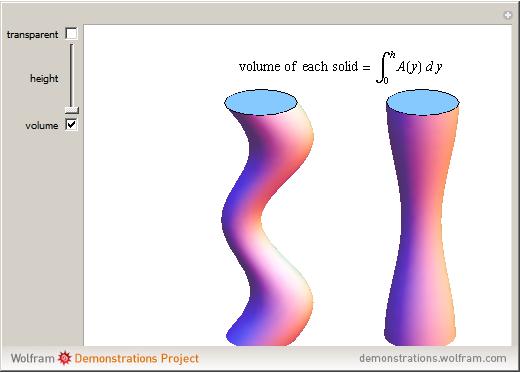

What would happen if you stacked the cross sections slightly askew? It turns out that the volume is the same! Why might that be the case? This is known as Cavalieri’s Principle and is illustrated nicely by the coins to the right, where it is easy to see both the cylindrical and wobbly stacks have the same volume. While this might seem obvious because each coin has some thickness, this works even with infinitessimally thin cross sections! They look very different, but the pyramids to the right have the same volume.

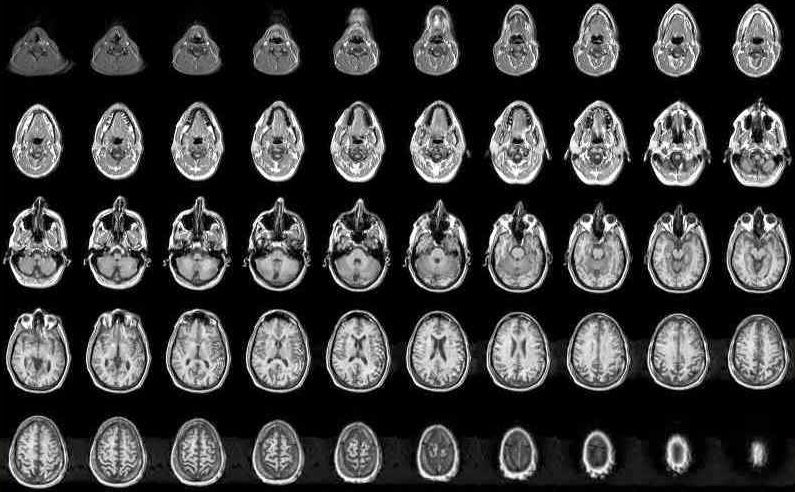

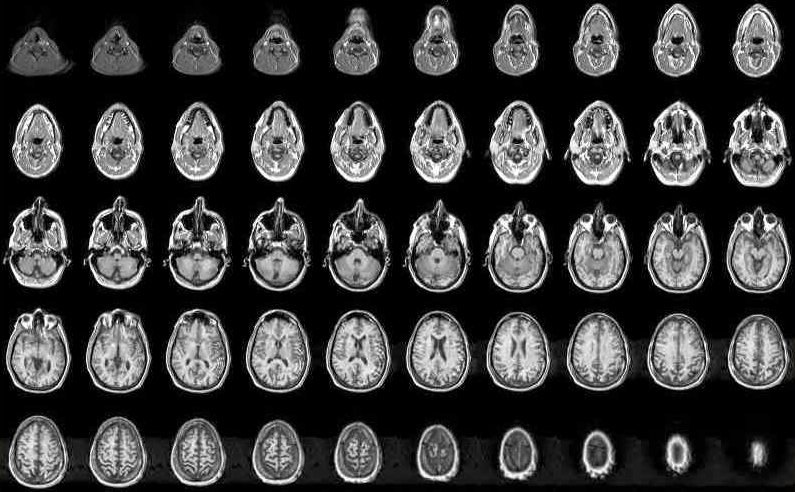

You might like thinking about how MRI brain scans fit together to form a 3-D brain.

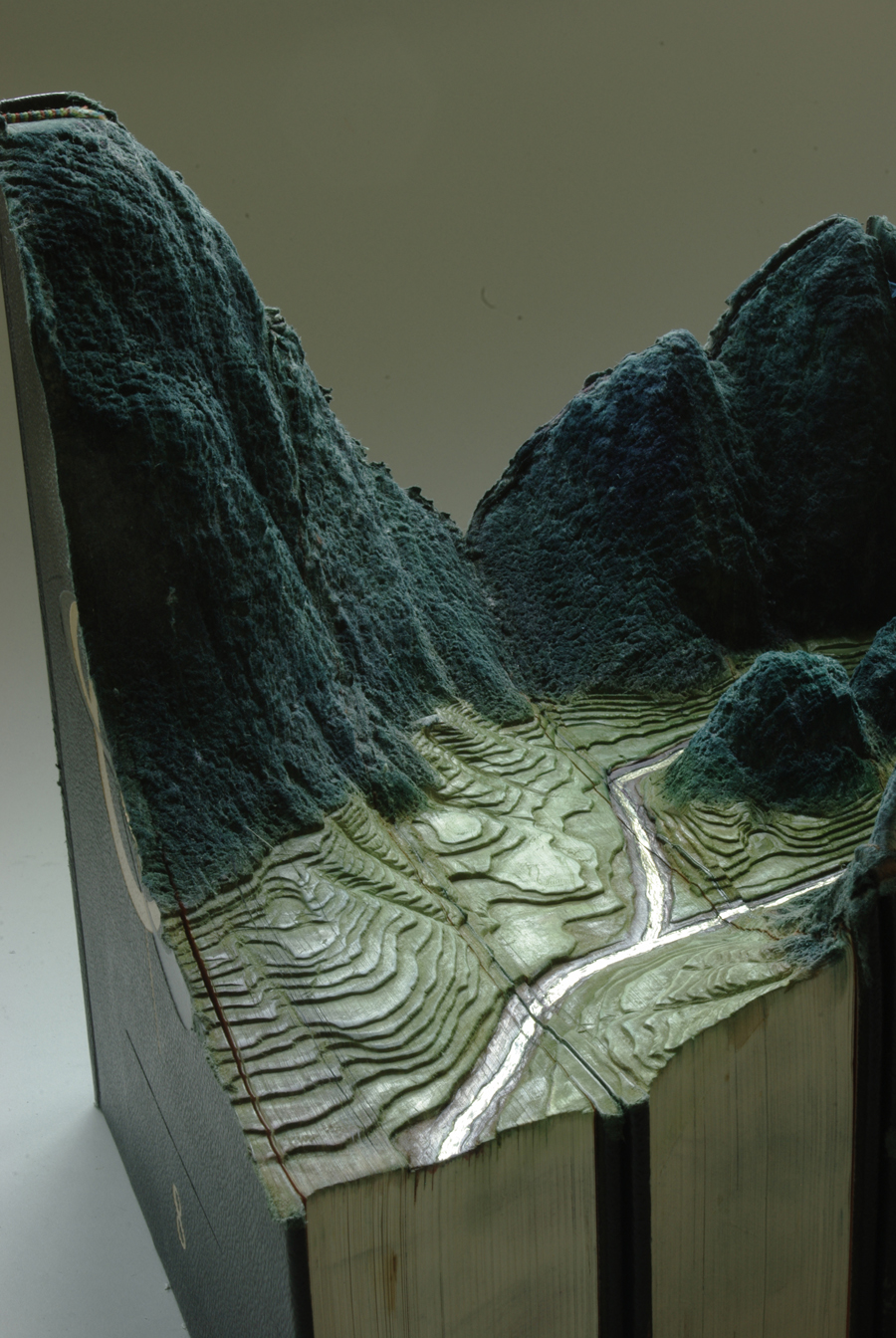

Artist Guy Laramée makes landscapes out of books. The pages are cross sections that come together to make a 3-D work of art.

Dorothy Hodgkin et al. produced this 3-D model of penicillin in the 1940’s using X-ray crystallography.

Here’s one cross section of a bagel. You can think about making a bagel by stacking up a bunch of thin bagel washers!

Edwin Abbott Abbott was an English schoolmaster and theologian. Abbott was a well-regarded author, publishing many works on religion, writing, and Francis Bacon. His most famous work, however was Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a novella he published under the pseudonym A Square.

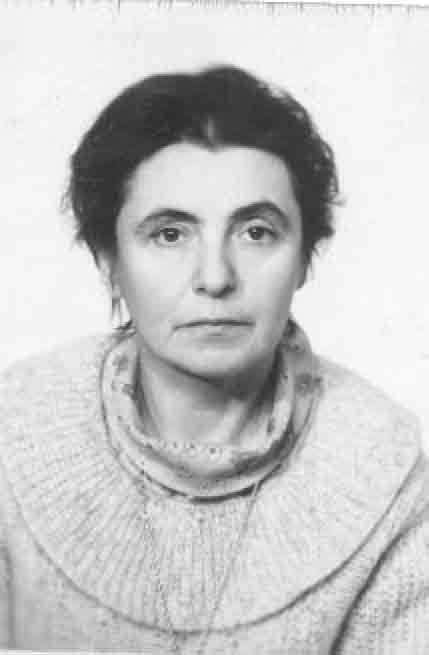

As cross-sections meld together to become a 3-D doodle, so do fluids follow the dynamics of the so-called Navier-Stokes equation, the focus of research of Russian mathematician Olga Ladyzhenskaya (1922 – 2004). A prolific mathematician, she published more than 200 scientific works on topics including partial differential equations, fluid dynamics, and the finite difference method.

Guy Laramée makes landscapes out of books. As you look at his art in the Gallery section, think about the way individual pages are the cross sections of his work.

Angela Palmer produces images like the ones in this exhibit. Some of her most recent work was inspired by the models of penicillin by Dorothy Hodgkin in the Oxford Museum of Science. Below, Angela describes her artwork:

“I developed this concept by drawing or engraving details from MRI and CT scans onto multiple sheets of glass, thereby layer by layer recreating human and animal forms, in particular the brain. The finished pieces, presented in three dimensions in a vertical plane, reveal the extraordinary inner anatomical architecture concealed beneath the surface, thus creating the most objective form of portraiture. The image floats ethereally in its glass chamber, but can only be viewed from certain angles – from above and from the side the image vanishes and the viewer sees only a void.”

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) views a living human body as a series of slices, just like the slices in a loaf of bread. Each scan produces an image of the cross section of the body along one plane, just like the plates in this exhibit. In order to understand the three-dimensional structure within the body, a large collection of slices must be collected and linked together. This can be done either by a computer, or by a skilled doctor using exactly the same kind of thinking as in this exhibit. Pictured are MRI scans of a human brain.

Edwin Abbott Abbott’s Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions was written in 1884. Since it is now in the public domain, there are many ways to find and read it online! Here is one link:

https://archive.org/details/flatlandromanceo00abbouoft

Wolfram Demonstrations Project has a nice applet that lets you explore the identical cross sections of two different objects. The applet can be found here:

http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/CavalierisPrinciple/