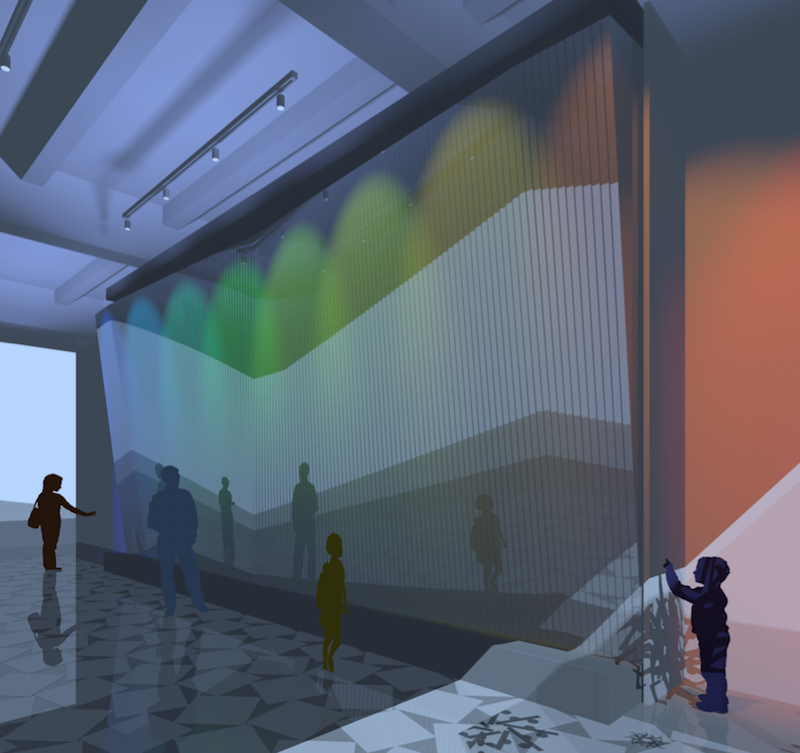

Look at the waves moving back and forth along the wall. Now look closely at the individual slats that make up the wall. They only go in and out. Their motion is driven by a computer that decides exactly how each piece should move to make the wave pattern. It may be a different pattern every time you visit, as MoMath tries out different rules and different patterns.

What shape are the wave patterns at the top of the wall and the bottom of the wall? Are they the same or different?

Waves come into our lives every day. Microwaves, light waves, seismic waves from earthquakes, sound waves, waves on water and stadium waves are all examples of waves. Math can help us to describe and analyze waves.

A wave is a disturbance which transfers energy without matter being transferred. The waves travel along Dynamic Wall but each slat ends up in its start position.

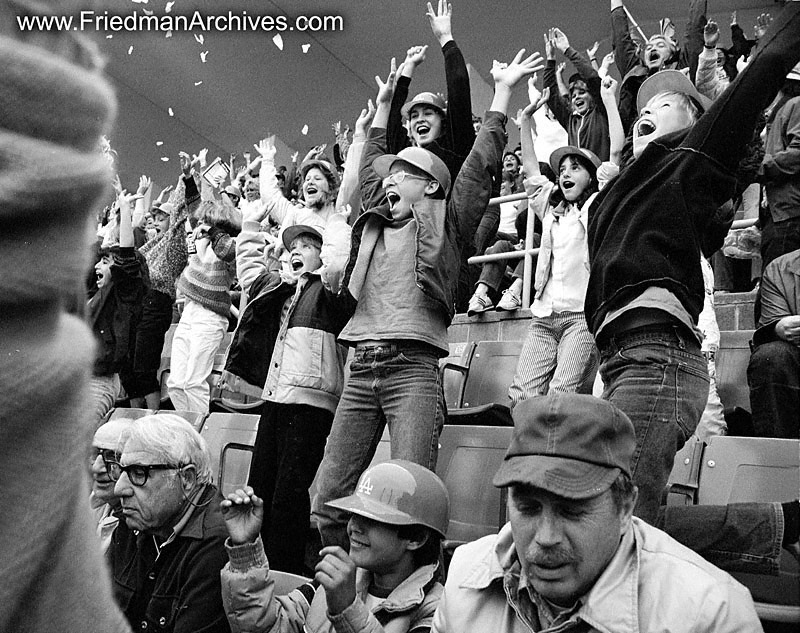

A stadium wave is another good example of this. Each person stands up and sits down in sequence so as to make a wave pattern travel around the stadium. The individual people (the “matter”) do not move around the stadium but by standing up and down they create a wave (“energy”).

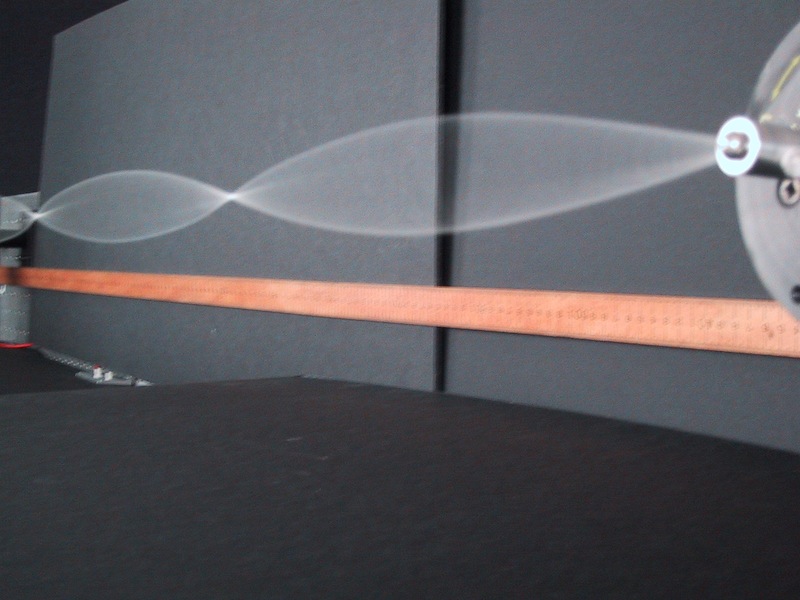

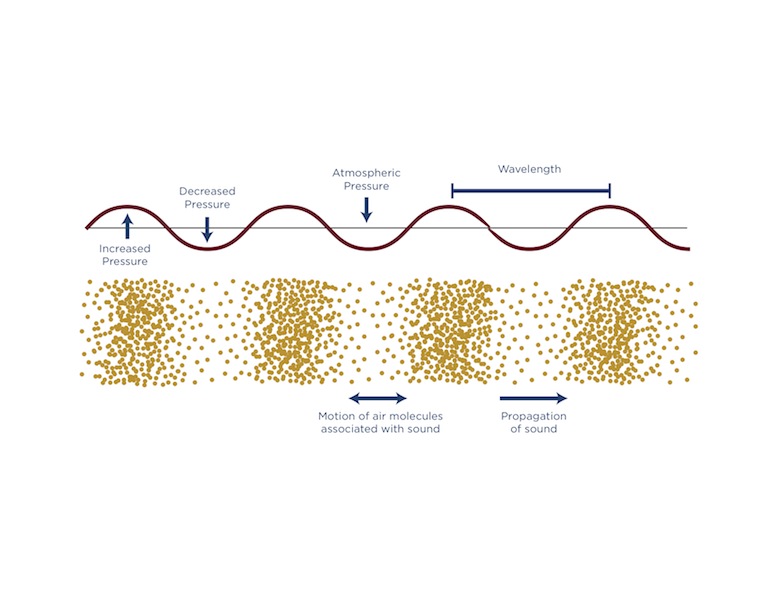

Three important features of a wave are its speed, wavelength, and frequency. The wavelength is the distance from the peak of one wave to the peak of the next one. In Dynamic Wall, frequency can be thought of as the number of times a slat moves in and out every second.

There is a relationship between speed, wavelength, and frequency. If the wavelength or frequency increase then the speed of the wave increases. If the wavelength or frequency decrease then the speed of the wave decreases. So when the number of times each slat moves in and out per minute increases then the wave will travel faster along the wall.

If the speed of a wave is fixed, then high frequency waves will have shorter wavelengths than lower frequency waves.

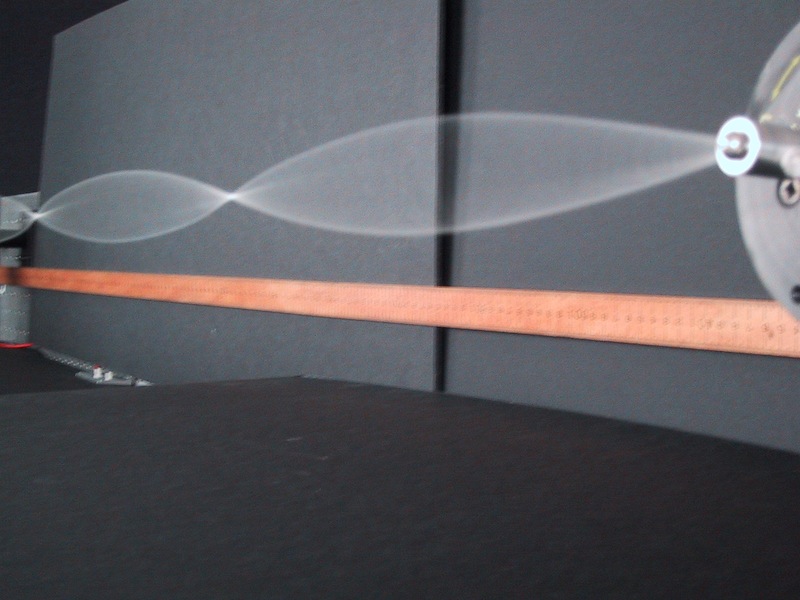

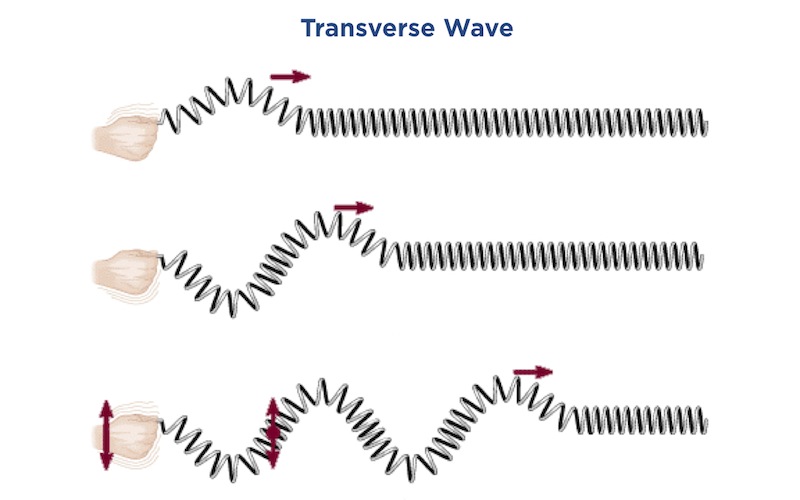

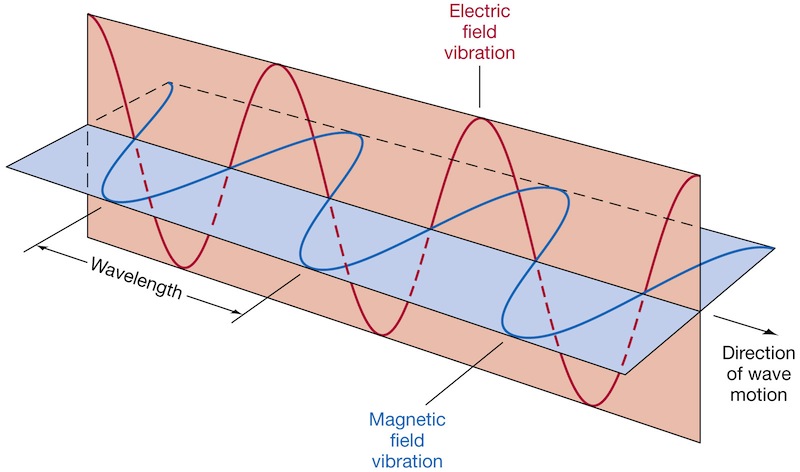

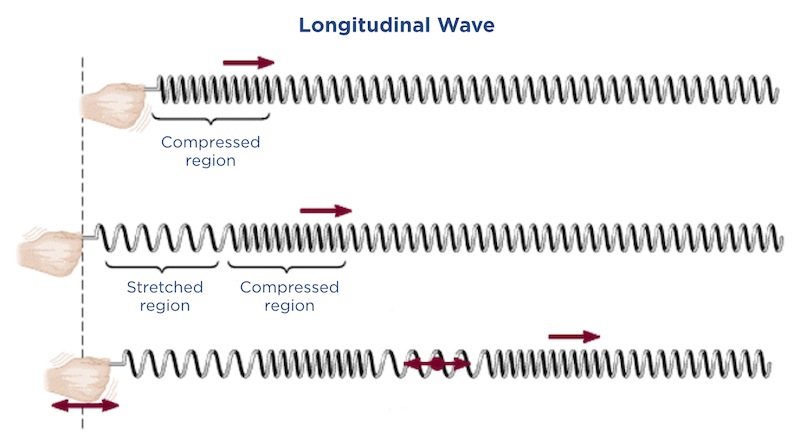

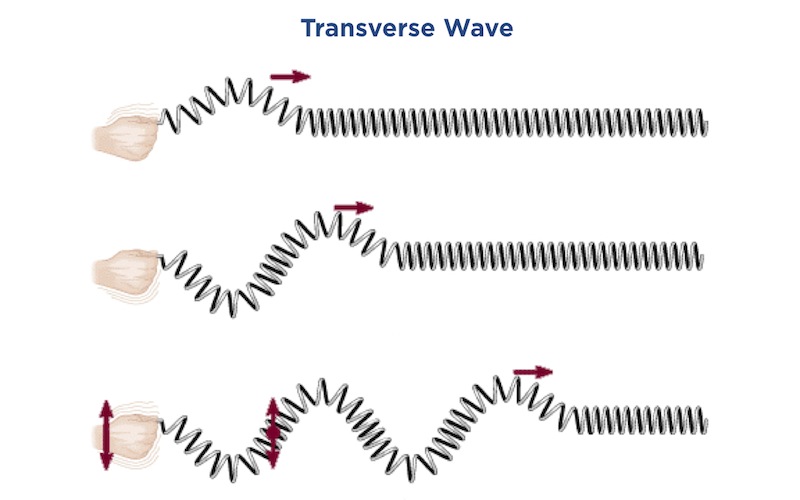

The slats on Dynamic Wall go in and out but the wave travels along the wall. This type of wave is called a transverse wave. You can make a transverse wave with a slinky. Stretch the slinky out then shake it up and down. The coils vibrate up and down but the wave travels along the slinky.

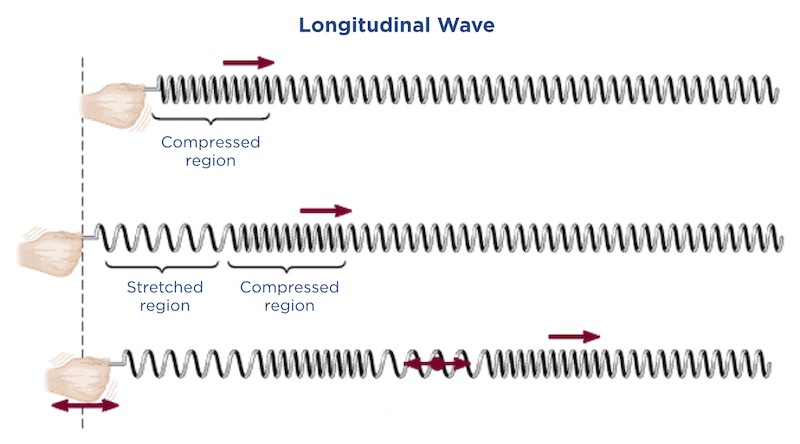

You can make a different kind of wave with a slinky: a longitudinal wave. Stretch the slinky out again, but this time push the end of the slinky in and out. The coils vibrate in the same direction that the wave travels in.

Sound waves are longitudinal waves. Light waves, microwaves and stadium waves are transverse waves.

Some waves need to travel through a liquid, solid or gas (called a medium). They are called mechanical waves and are caused by vibrations of the particles in the medium. Sound waves, seismic waves, and slinky waves are mechanical waves. Other waves, called electromagnetic waves do not need to travel through a substance. They are caused by vibrations in electrical or magnetic fields. They can travel through a vacuum like outer space where there are no liquids, solids, or gases. Light waves, microwaves, and X-rays are all electromagnetic waves.

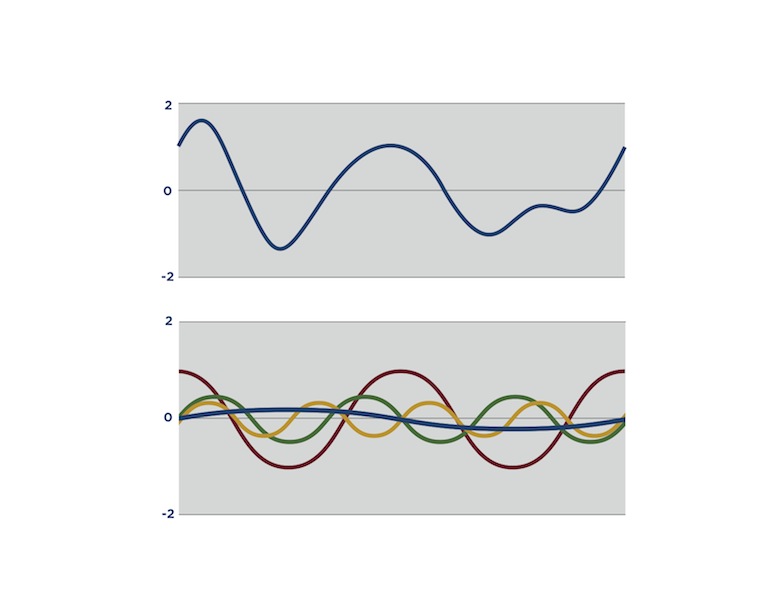

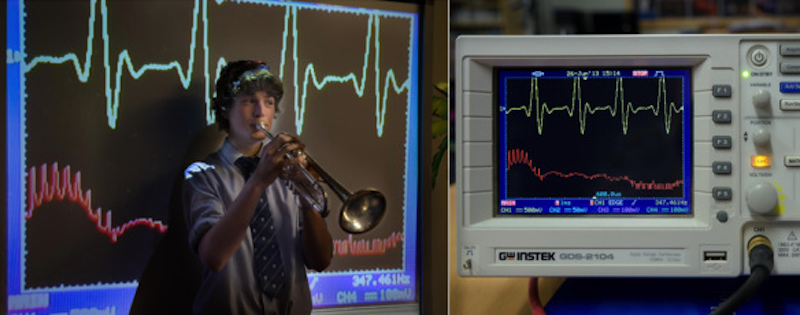

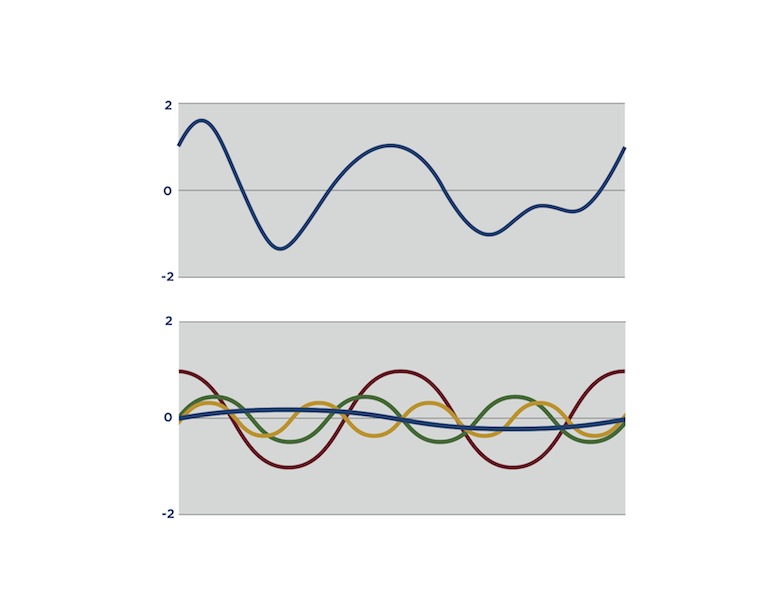

A note played on a musical instrument has undertones and overtones that make its waveform look very different to the sine curve. In fact many waves look much more complicated than the sine wave.

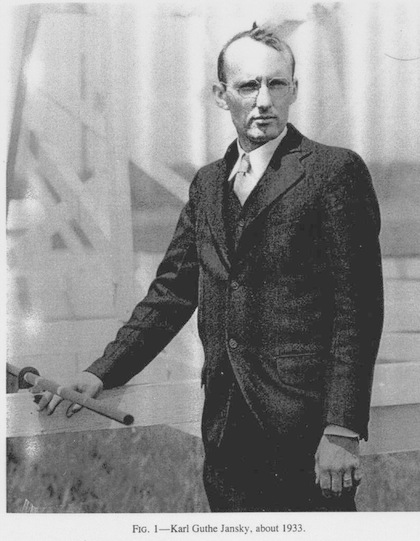

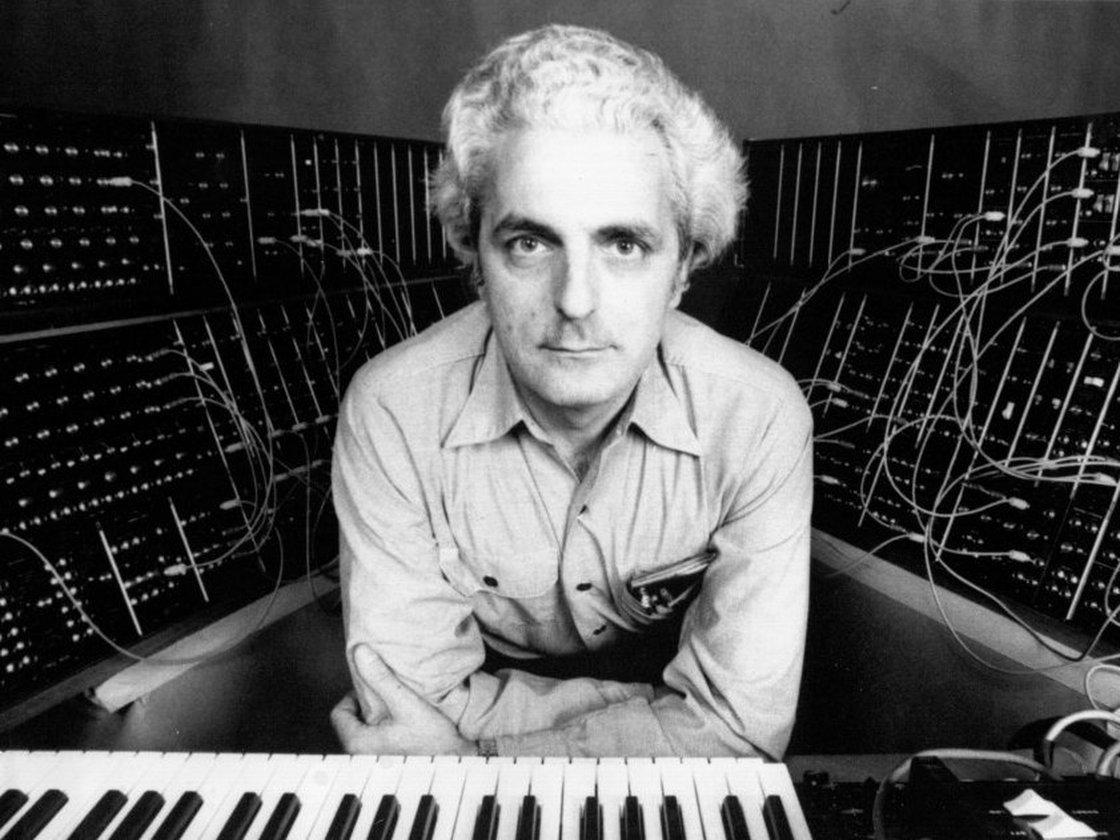

In the 18th century, Joseph Fourier discovered that sine waves with differing wavelengths and amplitudes can be used as building blocks for any wave. He proved this when studying heat transfer, but his discovery has been important for many fields. Musicians can recreate any sound or even create new sounds by combining sine waves electronically. Geologists can analyze complex vibrations caused by earthquakes. Astronomers can study stars by breaking down signals from space that they ‘see’ with radio telescopes. These are just a few modern day uses for Fourier analysis.

Israeli-American mathematician and computer scientist Shafi Goldwasser (b. November 14, 1959) is the RSA Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the National Academy of Science, she is the recipient of the Turing Award, often referred to as “Nobel Prize of Computing.” Innovative computer programming by computer scientists like Shafi are “behind the wall” here — and some of the exhibit’s behaviors were even designed by computer science students during a MoMath Hackathon!

Robert Moog (May 23, 1934 – August 21, 2005) invented the Moog synthesizer, one of the first commercially viable synthesizers. He was born in New York City. He attended the Bronx High School of Science and earned degrees from Queens College, Columbia University, and Cornell University. He used what he knew about waves and Fourier series to build instruments that create sounds that imitate conventional instruments and new, purely electronic sounds.

The properties of electromagnetic waves are used in a huge number of ways, including transmitting TV and radio signals, cooking food in a microwave and viewing the inside of the body with X-rays.

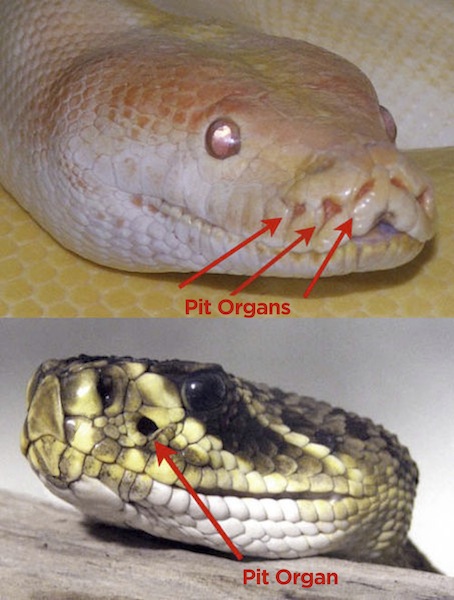

Infrared waves are a type of electromagnetic wave with a wavelength just longer than visible light. When you switch channels on TV you are actually sending pulses of infrared waves from your TV remote to tell your TV what to do.

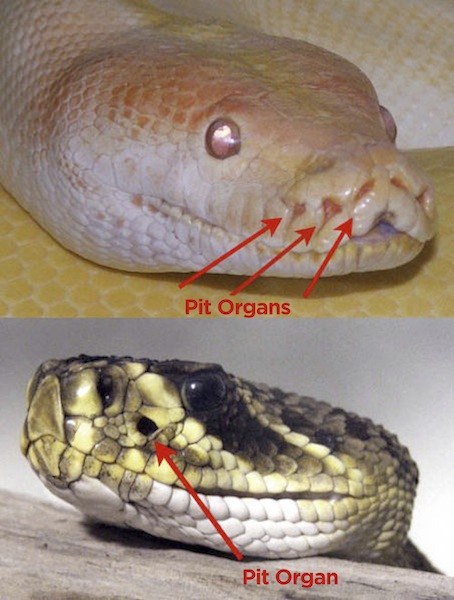

The red arrows in the pictures of the two snakes are pointing to special organs called pit organs. These organs are located between the nostril and the eye and can detect even tiny amounts of infrared radiation. This enables the snakes to “see” predators and prey in the dark.

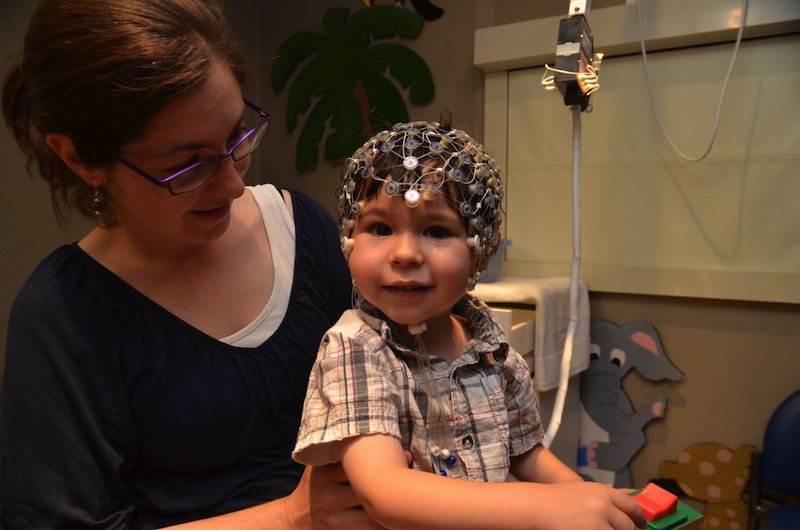

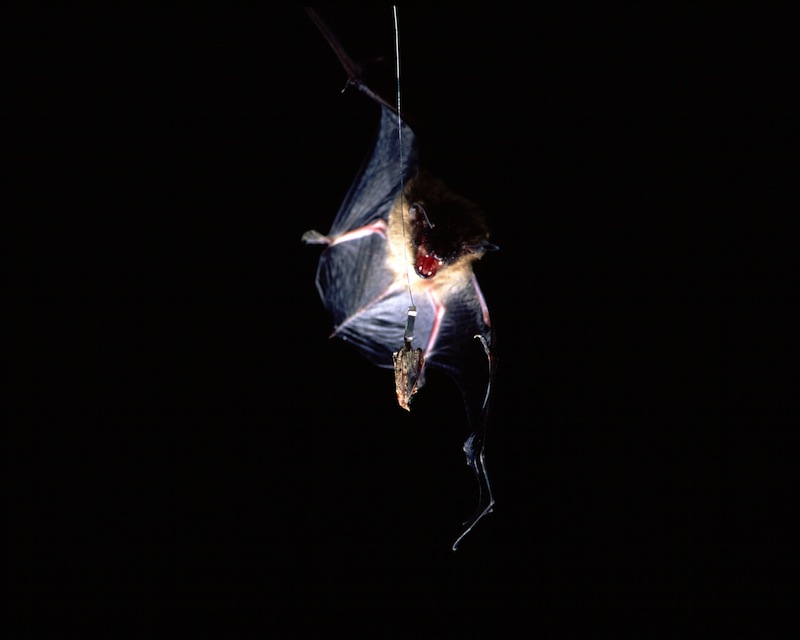

Ultrasound waves are sound waves with frequency too high pitched for the human ear to detect. Bats use ultrasound to locate and catch their prey. Ultrasound techniques are used to produce images of soft tissue inside the body. Ultrasound waves do not damage living cells so are considered safer for patients than X-rays.

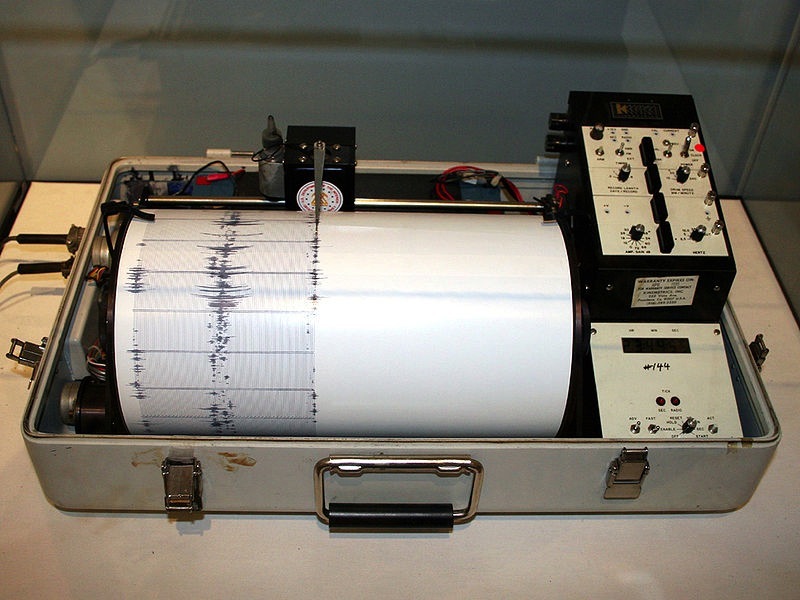

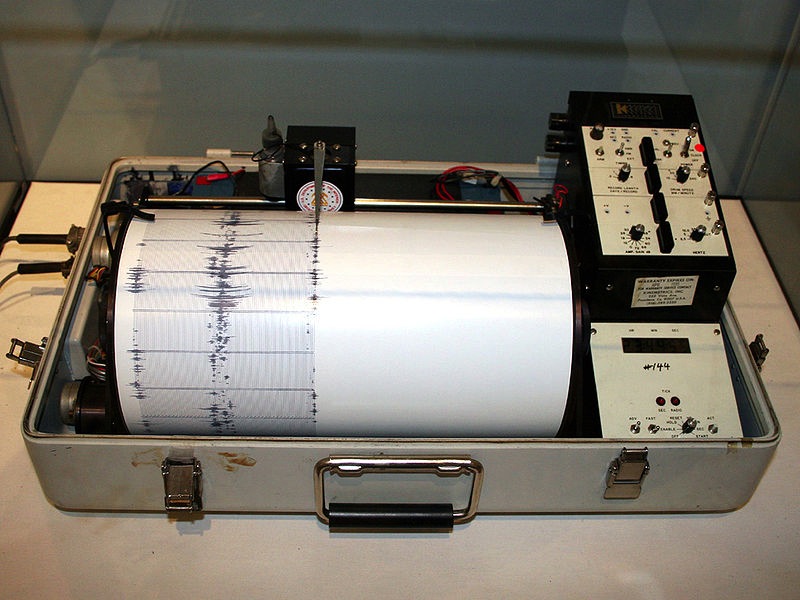

Geologists use machines called seismographs to study seismic waves that move through and around the earth. This can help them to save lives by predicting when earthquakes will happen.

A note played on a musical instrument has undertones and overtones that make its waveform look very different to the sine curve. In fact many waves look much more complicated than the sine wave.

In the 18th century Joseph Fourier discovered that sine waves with differing wavelengths and amplitudes can be used as building blocks for any wave. He proved this when studying heat transfer but his discovery has been important for many fields. Musicians can recreate any sound or even create new sounds by combining sine waves electronically. Geologists can analyze complex vibrations caused by earthquakes. Astronomers can study stars by breaking down signals from space that they “see” with radio telescopes. These are just a few modern day uses for Fourier analysis.

Sine is a ratio in trigonometry. Trigonometry is the study of relationships between the sides of a triangle. It was first used by people in the time of ancient Greece for calculations in astronomy. Graphing the sine wave was developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This math gave scientists a way to model waves such as sound waves in the field of acoustics and light waves in the field of optics.

Joseph Fourier (1768-1830) lived through the French revolution and was a scientific adviser to Napoleon. Fourier’s study of heat flow led him to the idea that sine waves can be used to build any wave. Fourier analysis is now used in many scientific areas, including building musical notes electronically using synthesisers, thinking about how we breath and how blood moves around the body, and making quantum computers.

This website gives tutorials on the math and physics of waves, with separate, more detailed explanations of light and sound waves.

An account of the link between math and sound waves (particularly those generated by musical instruments). Contains an accessible account of Fourier analysis.